The backstage scene before Stella McCartneyâs spring fashion show is part highfalutin glamour, part Romper Room: the designerâs young brood racing around as models shuttle from the makeup stations to their individual racks. In strides French retail and luxury titan François-Henri Pinault, who makes a beeline for McCartney, embracing her like a family member, patting the head of her three-year-old son, Miller, and tickling the chin of her nine-month-old son, Beckett. âDid you see the Chapman brothersâ mural?â McCartney asks, referring to the backdrop for her runway, a colorful felt playground scene by Dinos and Jake, best known for their sculptures depicting hell and other horrors. Pinaultâs smile wilts into a puzzled expression. âIâll have to show it to your father,â she offers, referring to billionaire François Pinault, who owns a staggering collection of modern and contemporary art.

Pinault flanked by Luc Besson and Yann Arthus-Bertrand, the green team behind the PPR-sponsored film, Home.

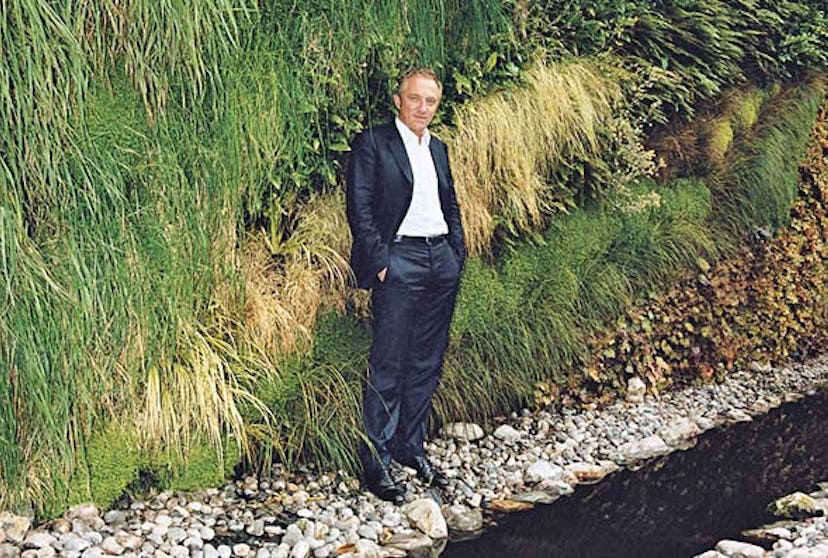

McCartneyâs backdrop for her fashion show a year ago was much more up the younger Pinaultâs alley: a lush, vertical garden by green-haired botanist Patrick Blanc that was later donated to a housing project in the gritty, have-not Paris suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt. The gesture encapsulated what seems likely to define the legacy of François-Henri, 46, who has quietly put social and environmental issues at the top of his agenda as chairman and chief executive officer at PPR, the French conglomerate that controls Gucci Group and retail chains such as Fnac and Conforama.

When Pinault established PPRâs Corporate Social Responsibility Department last year, his company was the first on Parisâs CAC 40 to appoint a director of CSR who reports directly to the CEO and who is a member of its executive committee. It was a powerful statement about social and eco responsibility, and he has incorporated it into PPRâs code of business practices, covering everything from employment diversity and fair-trade suppliers to reducing carbon dioxide emissions and building greener stores. Like other fashion and retail players, PPR trumpets its latest shops and stylesâbut the firm also emphasizes its smaller-format La Redoute catalogs printed on paper from sustainably harvested trees and its new charters with the European Works Council, an employeesâ advocacy group, to promote the employment of disabled people and aid senior citizens. If McCartney is the sustainable movementâs It girl, Pinault is the It boss.

âA business that ignores these issues, I donât see how it can be relevant in its economic activity,â Pinault insists during an interview in a wood-paneled conference room at PPRâs headquarters. âItâs a reality that if we continue the same practices vis-Ã -vis the environment, we will have a catastrophe. Everyone must react. There are about 90,000 people who work in this group. If they come to their senses, 90,000 people can bring awareness to their families: That could represent 200,000 or 300,000 people.â

A child’s eco-friendly bedroom set from Conforama.

If these arenât the typical subjects for a boardroom on the Avenue Hoche in Paris, Pinault isnât your typical business mogul. A down-to-earth sort with a ready smile and bright blue eyes, he long ago traded his âbig Aston Martinâ for a Lexus hybridâand has chastised his chauffeur for leaving the engine running in his company car. Pinault sorts and recycles all his garbage at home, and pays a fee to Action Carbone to offset the pollution created every time he takes a plane, private or commercial. Like all PPR employees, he prints on both sides of recycled paper, turns off lights when he leaves his office and uses videoconferencing to reduce his number of flights. Pinault allows that only a fraction of consumers today might make purchasing decisions based on the environment and the social behavior of a productâs maker. But heâs betting that very soon more and more people will decide what to buyâor what not to buyâbecause of such criteria.

âHeâs working with the only brand in luxury fashion thatâs not using leather and fur, so thatâs already an environmentally responsible act,â notes McCartney, referencing her company, a joint venture with Gucci Group. âI think François is ahead of the curve,â agrees Tomas Maier, creative director of Bottega Veneta, who uses vegetable dyes, shuns fur and carefully researches exotic skins to make sure they are procured ethically. âIn the face of a disposable culture, we are philosophically committed to making products that last. François knows that social and environmental change is essential andâ¦he has committed PPR for the long haul.â

Thus far, however, the fashion industryâwhich depends upon conspicuous consumptionâhas a poor track record. John Elkington, an author and a founder of the consultancy SustainAbility, says fashion operates on such tight production schedules that issues such as fast delivery, quality and price often âcompletely override ecological and wider social considerations.â He applauds companies like PPR that embrace CSRâeither because of moral conviction or in an attempt to stand out from the crowdâbut says, âIt will be interesting to see whether they stick with their principles when the economic slump really gets a grip.â

Jem Bendell, lead author of the World Wildlife Fund report âDeeper Luxury,â laments that luxury brands in particular are ânot doing enough to provide consumers with socially and environmentally elite products and services. Many companies are increasing their efforts, but there is a long way to go.â

Pinault credits the women in his life with instilling in him a sense of environmental and social responsibility, starting with his stepmother, Maryvonne, whom he describes as âlike Stella a generation earlier.â Growing up in Brittany in northwestern France, famous for gusty winds and rugged beaches, Pinault says he was her guinea pig for all manner of organic foods. âI tasted everything,â he says, his face flushing pink above a mint green shirt worn open at the neck. He describes his ex-wife, Dorothée, mother of his first two children, as a âmilitantâ for animal causes. (She once worked for the WWF.) âIf neither she nor I have dogs in Paris, itâs because she doesnât think dogs belong in a city,â he says.

More recently, Salma Hayek, his former fiancée and mother of his infant daughter, Valentina, has opened his eyes to her chief causes, which include preventing domestic violence and improving the health and living conditions of women in Africa. Indeed, Hayek arrived at the Balenciaga show in September straight from Sierra Leone, where she was pitching in on a tetanus vaccination program. âItâs she who made me aware of the problems of domestic violence,â Pinault says. âItâs the sort of topic that is silenced in Western countries. In France there is one woman who dies from domestic violence every three days. In France!â

A modest sort, Pinault gives credit to Serge Weinberg, his predecessor as CEO, for PPRâs initial efforts in CSR, which date back to the late Nineties. And he allows that many such efforts help the company save money. Still, the most recent impetus clearly comes from Pinault. One might not expect to find him on a rainy evening in the basement of a Fnac record store for a low-key cocktail party. But Pinault was there as a supporter and a board member of ELA, a French charity for sufferers of the rare brain disorder leukodystrophy, which strikes mostly children. âAs it is rare, there isnât a lot of research or much particular aid,â he says with a shrug.

Pinault worked his way up in his self-made fatherâs empire, starting in 1987 as a sales representative for a wood-importing business. He would later work in Pinault Sr.âs African trading company, CFAO, run the Fnac music and book chain, and then head up PPRâs Internet activities before becoming chief executive at PPR in 2005. Compliance with Pinaultâs green and social initiatives is now compulsory at PPR: A portion of the compensation of all top executives in the group is tied to it. Pinault also portrays CSR as a fearsome motivator for current workers and a compelling calling card to attract future employees.

Pinaultâs last big step was to establish a foundation that advocates for the dignity of women, a group that still faces glass ceilings. âI donât see how gaps in salaries can be justified or gaps in accessibility to certain responsibilities,â he says. The move is particularly appropriate because most of PPRâs workers and customers are women.

The lionâs share of Pinaultâs CSR efforts function below the radar, including antidiscrimination initiatives under a nonprofit organization called SolidarCité, which PPR established in 2001. People who buy couches at Conforama are not likely to be aware that the furniture, arriving at the Marseille port from Asia, is now shipped by river barge instead of trucks to a distribution center in Lyon, cutting carbon dioxide emissions by 800 tonsâand shipping costs by 20 percent. All stones used by Boucheron must have a certificate guaranteeing their adherence to the Kimberley process, assuring no âblood diamonds.â And astute shoppers will notice that the facades of Gucci stores in China go dark shortly after closing and remain so all night, even as those of many of its competitors are lit up like a switchboard at all hours. Whatâs more, last year Gucci received SA 8000 certification from Social Accountability Internationalâthe highest standard appliedâfor its leather goods and jewelry business, meaning that its supply chains comply with standards for decent working conditions based on UN conventions and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

There have been a few initiatives of the headline-making ilk, including a Madonna-hosted Gucci bash during New York Fashion Week this past February that attracted stars such as Demi Moore and Tom Cruise and raised $5.5 million to be split between UNICEF and Madonnaâs Malawi charity. Gucci has also tapped Rihanna for an ad campaign this winter promoting special-edition products for UNICEF. âIt makes all the difference,â the singer insists. âWhen [customers] see that theyâre taking a chunk of their profits and giving it to UNICEF and the kids, itâs really deep. I give them so much more respect.â

Pinaultâs next big green initiative will be one thatâs hard to missâand he hopes no one will: Heâs underwriting a film called Home, by Yann Arthus-Bertrand, who is famous for his âEarth From Aboveâ portraits taken from helicopters and balloons, and produced by Luc Besson. âI decided in 10 minutes to do it,â says Pinault of the project, which is designed to raise awareness through breathtaking images illustrating the major social and eco challenges facing the planet. The film, scheduled to be released worldwide on June 5, 2009, World Environment Day, cost PPR 10 million euros, or about $13 million. (It will be distributed free of charge on the Internet and television and in movie theaters, which are expected to charge reduced admission.) âAs the budget for a film without actors, itâs absolutely colossal,â Pinault says. âThe objective is to scale the planet and reach hundreds of millions of people. Itâs a subject that really touches me.â

âI think François is sincere in that,â says Besson, who faces the task of choosing from 155 miles of film shot in more than 50 countries. âThereâs this moment in your head when you say, âThis is serious. We canât ignore it.â Have you noticed how many children today are bothering their parents? They get it, and we have to do it for them.â And while Besson, tugging at the hem of his oversize black T-shirt, is hardly a fashion plate himself, he says heâs heartened that Pinault, whom he has known for 15 years, is putting a high-profile industry behind the sustainability movement. âI hope the consumers in fashion will help,â he says. âThey can help just by choosing the ones that make an effort.â

Furniture: courtesy of Conforama; Pinault with Besson and Arthus-Bertrand: Thomas Sorrentino