Catching Up With George Clooney

The stellar actor opens up about his upcoming film The Monuments Men, Hitler’s art collection and his cinematic crush.

In The Monuments Men, which is due in theaters in early spring, George Clooney plays the leader of a special platoon of museum directors, curators, and art historians who join forces to rescue the art that Adolf Hitler stole during World War II. Based on actual events, the movie is a men-on-a-mission thriller that asks a larger question: Do cultural artifacts define the spirit of a country? “Art takes different forms,” said Clooney, who coproduced, cowrote, and directed the movie. “But it represents something that is basic in all of us—our history.”

Clooney became interested in the story through his writing and producing partner, Grant Heslov, who had picked up Robert M. Edsel’s 2009 book The Monuments Men in an airport. “Grant and I had been talking about doing a movie that was a little less cynical than what we normally do,” he said, citing films such as Argo (for which Heslov, Clooney, and Ben Affleck won the Academy Award for Best Picture this past February) and Michael Clayton. “We tend to like cynical films because we find them more interesting. But we wanted to do a movie where the good guys win and you’re fighting the ultimate bad guy—Hitler. This was a story that nobody had heard about.”

What cultural icons have mattered most to you? I grew up Catholic, and there were always religious icons that I’d see in church. The cross and the altar were big parts of my life. But when I was 10 years old, my father took me to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. I remember walking up those stairs and looking at this carved piece of marble that had nothing to do with a carved piece of marble. That statue said something to me about us as a society. In The Monuments Men, we question whether saving art is worth a life, and I would argue that the culture of a people represents life. When the Taliban destroy incredible pieces of architecture and art, or when American troops don’t protect museums in Iraq, you are seeing people losing their culture. And with the end of a country’s culture goes its identity. It’s a terrible loss, down to your bones.

Hitler was amassing an enormous art collection. Was he planning to open his own museum? Yes—he wanted to build a Führer Museum. He had a model of it in the bunker with him! He wanted to steal all the great art in the world, and he was well on his way—during the war, he collected 5 million pieces. He also destroyed works he termed “degenerate art.” The Nazis took amazing Picassos and Klees and Mirós and burned them in the garden outside the Jeu de Paume museum in Paris. They wanted to prove that they were illegitimate and had to be destroyed. Hitler pulled off the greatest art heist in the history of the world—luckily, some of that art has been recovered.

Wasn’t Hitler a painter before he became a politician? Yes, he was a failed artist in Vienna. In the film, we show a couple of his watercolors. If he had only been a little bit better at painting, history might be different.

Did Hitler have particular artists he favored? He loved da Vinci! Starting in the late 1930s, he sent professors to the greatest museums in the world to have “meetings,” but they were secretly making lists of all the paintings and their locations for Hitler. When the Nazis conquered a country, he would take the art.

I’m guessing The Monuments Men has a happy ending. And Argo has a terrific finale. What are your favorite movie endings? Watch the end of It’s a Wonderful Life, the Frank Capra film. You can’t end a movie that way anymore—today, Lionel Barrymore, the bad guy, would be hauled away in handcuffs. But Capra doesn’t do that. Barrymore just goes on home, and that’s it, the end. We forget about him and forgive him because Capra’s idea of a perfect ending was “living well is the best revenge.” I tend to like endings that would never happen in today’s movies. In 2013, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid wouldn’t end the way it does. I’ve shown that movie to young kids who just love the film, and then you come to the last scene—a freeze-frame of Butch and Sundance getting shot—and their mouths drop: “No, no, no, no.” Films from the ’60s and ’70s end in shocking ways. And that’s why we love them—those movies broke all the rules.

Gravity, in which you costar with Sandra Bullock as astronauts stranded in space, is a surprising, nontraditional film. You are alone for the entire movie. Was it hard to act in that solitary environment? I actually like working by myself. [Laughs.] Truthfully, I was constantly in motion. The trickiest part was learning to speak quickly and move 50 percent slower because you are in space. It was not fun in the machinery—I have a bad back and a bad neck, so that part was not fun. But you have to step back and look at my life. I’m lucky enough to get to work on these projects.

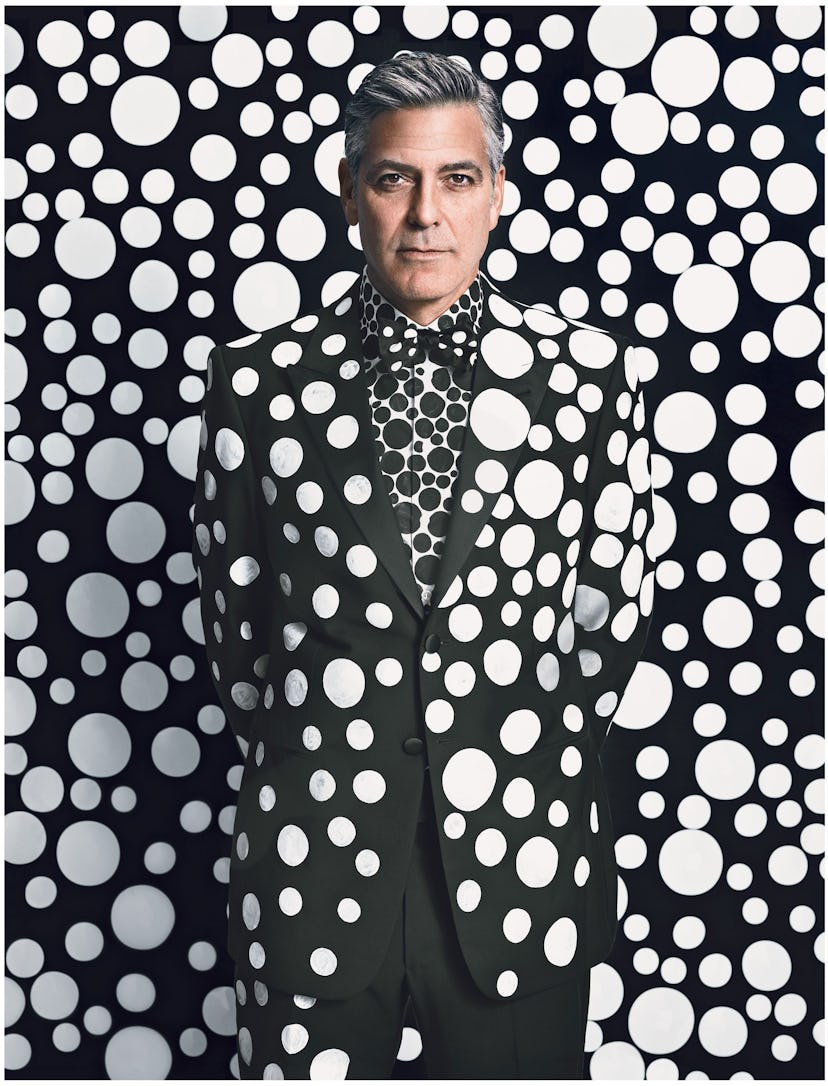

When you make a film like Gravity, you are a kind of muse for the director—in this case, Alfonso Cuarón. Similarly, in this project for W, you were a muse for five female artists. How did that feel? [Laughs.] Yayoi Kusama depicted me covered in polka dots. She made me Snoopy! But I must say: I’m proud to be Snoopy! Ultimately, what I’m trying to do with a director—or, I guess, an artist—is to be of service to them and their story.

In her questionnaire, the artist Tracey Emin asks you about the love of your life. But who is your cinematic crush? When I was a kid, I was in love with Audrey Hepburn. I watched Roman Holiday when I was 11, and I thought she was as elegant as anything I’d ever seen. And I fell madly in love with her. I also always loved Grace Kelly. I mean, when she comes out of the water in To Catch a Thief, I thought, That’s the most beautiful woman I’ve ever seen.

George Clooney: Spot the Star

George Clooney on the cover of W’s December/January issue.

Giorgio Armani suit, shirt, and bow tie, prices upon request, Giorgio Armani, New York, 212.988.9191.

Yayoi Kusama

In the late ’60s, Kusama’s celebrity rivaled that of Andy Warhol. A central figure on the New York avant-garde scene, Kusama was famous for her delicately patterned abstract canvases, soft furniture with phalluses, and happenings in which she painted naked participants with her now signature polka dots. She also had her own clothing shop, where she sold her racy designs. But when the emotional issues that had plagued her since childhood proved overwhelming, she quit New York and entered a Tokyo psychiatric hospital, where she has resided ever since. And yet she has never stopped producing bold, propulsive work that spans painting, sculpture, fashion, and installation, such as her mirrored infinity rooms, which surely reflect the cosmos of Kusama’s own imaginings. The sources for her celebrated polka-dot works, for example, are the hallucinations she first experienced as a child growing up in Japan during the war years. “Polka dots would cover my fingertips to the top of my head, expanding to the window and finally covering up the whole room,” says the artist, 84, whose latest solo show of new paintings and installations, “I Who Have Arrived in Heaven,” is on view at David Zwirner in New York through December 21. She adds: “I was terrified by these hallucinations, so much so I had to tremble in the closet. However, by painting these psychological complexes and fears repetitively, I was able to suppress and overcome all of them.” Early in her career, Kusama commissioned photographs of herself with her work, in which she often dressed to blend in with the elaborately polka-dotted settings. “I call it Kusama’s Self-Obliteration,” she says of an artistic philosophy that, perhaps ironically, has put that self front and center. Though she knew little about George Clooney, she decided to suit him up in polka dots as well. “My idea is to send the message of ‘love forever’ to all the people in the world through the polka dots, which are all about the universe and human beings and living things. Your sex, being famous, being a star has nothing to do with it.”

Giorgio Armani suit, shirt, bow tie, and shoes, customized by the artist Yayoi Kusama; Thomas Pink socks. Styled by Michael Kucmeroski. Set design by Thomas Thurnauer. Photography assistants: Dean Dodos, Charles Grauke, Alexandre Jaras; Fashion assistant: Anastasya Kolomytseva. Purchase this image on Artsy.

Yayoi Kusama. Giorgio Armani suit, shirt, and shoes, customized by Yayoi Kusama. Styled by Michael Kucmeroski. Set design by Thomas Thurnauer. Photography assistants: Dean Dodos, Charles Grauke, Alexandre Jaras; Fashion assistant: Anastasya Kolomytseva. Purchase this image on Artsy.

Karen Kilimnik.

Kilimnik has painted Paris Hilton as Marie Antoinette, drawn ballet star Rudolf Nureyev, and turned London’s Serpentine Gallery into a suite of rooms inspired by stately homes, equestrian themes, and the occult, but until now she had never made a drawing of Clooney. The famously reclusive artist, who worked from her recollections of the actor on the red carpet and in the film Ocean’s Eleven, says the most difficult Clooney quality to capture was “his sense of humor.” Kilimnik’s latest show of paintings and photographs runs through March 31, 2014, at the Prince of Conti’s 18th-century winery in Burgundy, France. Purchase this image on Artsy.

Marilyn Minter

In her hyperrealistic photographs and paintings, Minter, 65, taps into our anxieties about glamour and desire. Look closely at her glossy gold-encrusted mouths, tongues spewing pearls, or feet teetering on spiky sandals and they suddenly go all blurry—they are, and they aren’t, what they appear to be. A key part of the New York art scene since 1969, when she made the now famous photographic series of her drug-addicted, agoraphobic mother, Minter will be among the artists featured in the gallery show “Bad Conscience,” at Metro Pictures in New York from January 16 through February 22, 2014. “I’m interested in cultural leftovers—images that you don’t really see because they are waiting to get replaced or swept away,” she says. For W, she imagined Clooney as the figure on a movie poster that is about to be removed from a bus shelter or a billboard. She worked from original close-ups of Clooney’s pores, stubble, and eyes; on her computer, she made his eyelashes more prominent, then graffitied the cracked glass with markers and swiped a glycerine-water mixture over it to mimic the effect of rain. Finally, she set up a light to create a flare in his pupil and shot the image with her digital camera. In the end, Minter says, “I chose to wipe him out altogether so that he just became a male eye.”

Catherine Opie

The first “out leather dyke from California,” as she puts it, to earn a major solo show at New York’s Guggenheim Museum, in 2008, the 52-year-old artist has never shied away from confrontation or candor. For a 1994 self-portrait, she wore a leather hood and had the word pervert cut into her bare chest; a decade later she posed topless as her infant son suckled her nipple. (That work is featured in the group show “Me. Myself. Naked” at Museen Böttcherstrasse, in Bremen, Germany, through February 2, 2014.) Although the construction of identity has long been the subject of her work—she is best known for her documentary-style photographs of archetypical communities including surfers, football players, and lesbian families—Opie has also trained her lens on freeways and rural landscapes. Over the past couple of years, she has shot close artist friends like Matthew Barney, Raymond Pettibon, and Kara Walker against a black background, in hopes of investing her photographs with more narrative mystery. The goal, she explains, is to allow viewers “to load their own sense of story onto an image.” Though she’d never met him before, George Clooney, she decided, fit neatly into her concept. “I told myself this was just another person I had asked to come to the studio,” she says. Of course, his renown as “the go-to romantic guy,” Opie explains, led her to explore the expectations that come with a portrait of a male movie star and to “tweak them.” For starters, she left the actor barefoot and played with poses from John F. Kennedy’s official portraits, among others. A lover of 17th-century painting, Opie looked to Hans Holbein as inspiration for her earliest sittings; lately, Leonardo da Vinci has led her to think about light and how it breaks and illuminates certain areas while pulling others into shadow. Wanting Clooney to appear as if he were emerging from a private reverie, she moved the lights herself and kept the set music-free. “I didn’t want just a stare; it had to be a human moment,” Opie says. “Ultimately, I’m interested in the silence that portraits can offer.”

Giorgio Armani suit; Emporio Armani shirt; Omega watch. Styled by Michael Kucmeroski. Purchase this image on Artsy.

Catherine Opie

Giorgio Armani suit; Emporio Armani shirt; Omega watch. Styled by Michael Kucmeroski.

Tracey Emin

Emin, 50, was a writer before she was an artist, and words drive her confessional, in-your-face works. The piece from 1995 that made her famous, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995, consisted of a camping tent with the names of everyone she has ever shared a bed with stitched inside. Having grown up in the seaside town of Margate, England, surrounded by neon signs, she put her own name in lights that same year—for the Tracey Emin Museum she created in London. “My neon is hand-blown and hand-twisted and follows directly from my handwriting, which is very distinctive,” says Emin, who considers her longhand script as expressive as a drawing. “It’s all joined up and quite old-fashioned-looking,” Since 2009, she has also made text portraits (opposite) based on a standard questionnaire (above) she asks each subject—in this case, George Clooney—to complete. Emin knew Clooney only through his films and political activism, and his e-mailed answers made her “burst out laughing,” she says. “They were so candid. So I thought about how strong his smile is, because he’s definitely funny.” His humble notion of home also intrigued her. “I could imagine him sitting there on his own, writing notes, thinking about it. You can tell by his answers that he has this strange time, this no-man’s time going from one place to another.” Emin says that her subjects’ responses are often more revealing than what any in-the-flesh sitting might produce. “It’s a collaboration in the simplest way,” says the artist, whosefirst U.S. museum show, “Angel Without You,” which focuses exclusively on her neon works, opens at the Museum of Contemporary Art in North Miami on December 4 (through March 9, 2014). “I’m asking them to guide me by what’s in their mind—but they’re influenced by my questions.” Her question about sex, for example, “reveals to me how up-front they are or how much they could possibly take in their own environment,” and the one asking how they’d choose to die “lets me see how vain they are—you know, if they say, ‘being shot into space’ or whatever.”

Tracey Emin