The Art of The Deal

Part P.T. Barnum, part Tim Gunn, Simon de Pury is much more than the art world’s most controversial auctioneer. Diane Solway meets the aristocrat, amateur DJ, and reality-TV star.

In June 2010, after he’d secretly married his longtime associate Michaela Neumeister in London, Simon de Pury, the chairman of Phillips de Pury & Company auction house, wanted to mark the occasion with friends. But being de Pury, an auctioneer who’s equal parts showman, performer, and connoisseur, he felt that the celebration called for something that might guarantee their 600 guests—the jaded jetset of the art world—a priceless experience.

A hip-hop aficionado who moonlights as a DJ, the 60-year-old de Pury knows how to get a party started: He commissioned food artist Jennifer Rubell, daughter of Miami megacollectors Don and Mera Rubell, to stage an installation at London’s Saatchi Gallery. When the guests arrived, de Pury and Neumeister were on display in separate glass-fronted cubicles, getting ready for the evening. De Pury shaved and had his hair cut before shattering his doorway—with a hammer, of course—and then retrieved his bride by breaking hers. Soon everyone was invited to toast them, toss their champagne glasses off a balcony, and eat from the his and hers spreads arrayed alongside each of their dressing rooms. Sausages hung from the ceiling over a plinth stocked with beer near de Pury’s; 2,000 oysters and bottles of champagne were laid out next to Neumeister’s. The de Pury Diptych was rife with none too subtle symbolism.

Downstairs, the assigned dinner tables were actually 69 unmade beds— a nod to Tracey Emin’s signature work—heaped with silver platters of crayfish, whole hams, roasted chickens, and piles of quiches. “People were hopping from bed to bed,” said de Pury, recalling how his friends—among them, Emin, photographer Mario Testino, and Charles Saatchi—had to tear into the feast with only their hands and knives. “People didn’t know what to do until they realized they had to participate.” Dessert arrived on yet another floor, below, in the form of 100 wedding cakes made by 100 different London bakeries, presented on individual stands, “so the room looked like a Wayne Thiebaud painting,” he said. “And then I DJ’d a bit for people to dance. It was really an art performance.”

To the Swiss-born de Pury, all the art world’s a stage. “He’s the Jeffrey Deitch of the auction world, always seeking the most theatrical, the most spectacular performance or artwork, irrespective of its quality,” said collector Adam Lindemann, author of the 2006 book Collecting Contemporary, who met his wife, the dealer Amalia Dayan, while she was working at Phillips. “Simon needs a happening; he’s addicted to the adrenaline. He’s got a tremendous career, but he’s also obsessed with the newest thing. Most times after a long tenure in the art world, you become jaded. But Simon is willing to do anything. He’s a man on a mission.”

From left: Jerry Saltz, de Pury, China Chow, and Bill Powers, judges and mentors on Bravo’s Work of Art.

Among his latest roles is that of mentor to aspiring artists on Bravo’s Work of Art: The Next Great Artist, which just returned for a second season after drawing 1.4 million weekly viewers last year. His stint on the show has raised eyebrows, of course, and not just those of his colleagues, many of whom claim never to have seen it—“On a reality show is exactly where he belongs,” sniffed one prominent Berlin dealer—but also those of his costars. Fellow judge Jerry Saltz, New York magazine’s art critic, called the choice of him as mentor “misguided,” and added, “I love the guy, but the head of a swanky auction house—which is about making money—shouldn’t advise young artists about anything, ever.”

The criticism doesn’t faze the ever camera-ready de Pury, who enjoys nothing more than upending expectations. “I didn’t have any reservations,” he noted, admitting that he watched only last season’s first and final episodes but helped cast the artist-contestants for the new season. “I always felt there was a misconception that art was elitist, and I like the fact that it shows you precisely what it is to create a work of art and to judge one. And the fact that it does so in an entertaining way—so much the better.”

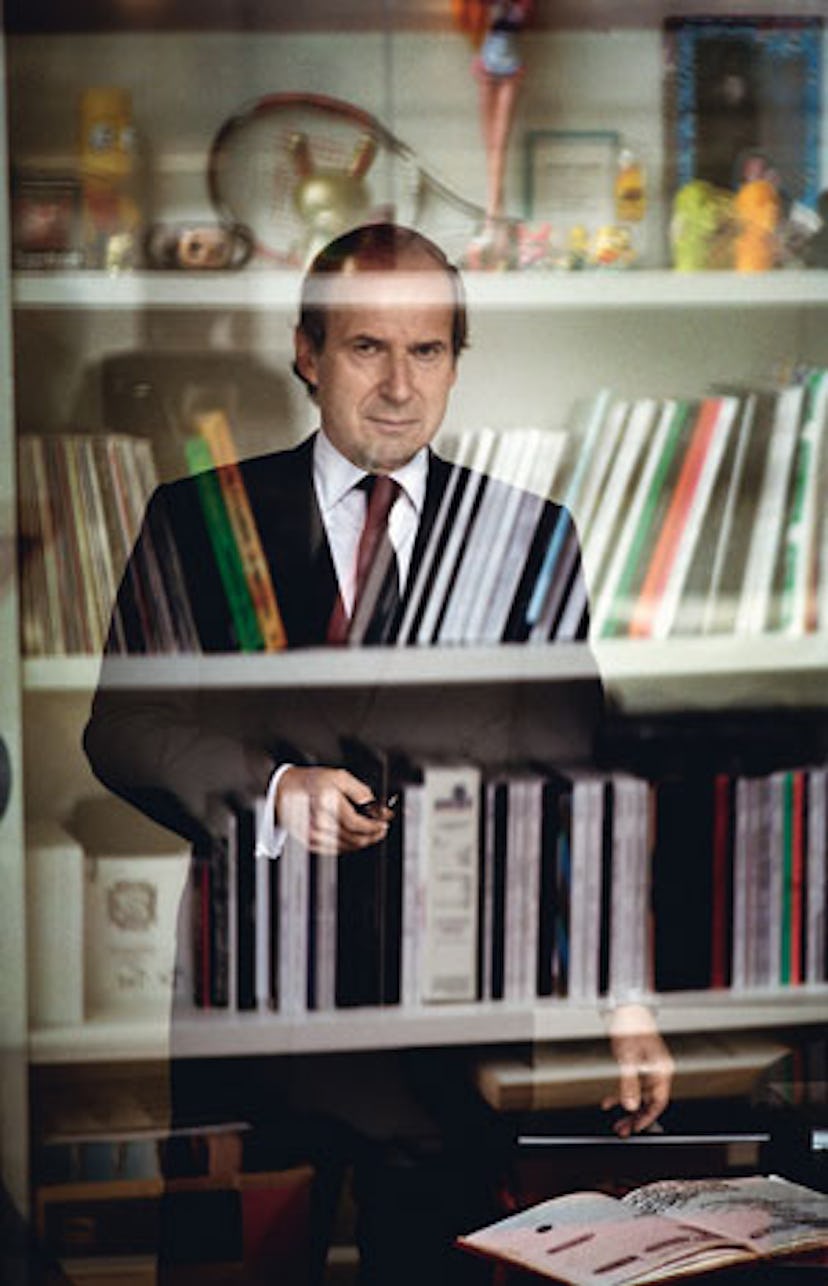

He’s been called the Mick Jagger of auctioneers for the sizzle he brings to the salesroom, but on first meeting, de Pury more readily suggests a fusty aristocrat. He favors French cuffs and tailored double-breasted suits with gold buttons, wears his side-swept hair behind his ears, and speaks with a Mittel-European accent and in four languages; in this casual age, his manners seem a holdover from a lost era. Meeting a woman for the first time, he’s likely to kiss her hand. And at an August benefit in the Hamptons for Robert Wilson’s Watermill Center, he refused to take off his jacket while dancing wildly, even though he was dripping with sweat.

“There’s this tremendous Swiss restraint combined with a hint of old-world decadence,” said Lindemann. “He’s culturally at home in many places, and not just in Europe or America or Asia,” said the art publisher and collector Benedikt Taschen, a friend for over 20 years and de Pury’s soon-to-be singing partner in a concert they’re cooking up for their pals. “He’s never made any distinctions between so-called high and low.” He once organized a hip-hop jewelry auction to lure younger collectors, and you’ll find him on YouTube in a Euro-pop rendition of “If I Had a Hammer,” featuring de Pury at the rostrum and actors bopping to the beat while pumping their fists in the air. This past March, he appeared on The Colbert Report, proclaiming his love for the music of “Snoopy Dogg”—as he inadvertently called the rapper—and busting some moves with the host before selling a self-portrait of Stephen Colbert, amended by Frank Stella, Shepard Fairey, and Andres Serrano, in an auction at Phillips. (Colbert himself hammered the work at $26,000.)

Top: Mario Testino, Kate Moss, and Simon de Pury at the opening of the exhibit Mario Testino Kate Who?, at Phillips de Pury & Company in London. Below: de Pury, DJ’ing at the 10th-anniversary party for RxArt.

Not surprisingly, de Pury has created a rambunctious pop mood at Phillips, the underdog auction house regularly characterized as “struggling” by the art press, as its manpower, sales, and reach are considerably smaller than those of behemoths Sotheby’s and Christie’s. But Phillips is also seen as a bold—some say flashy—innovator, especially since the Russian luxury-retail giant Mercury Group bought the controlling stake in the company three years ago. Mercury is run by Leonid Strunin and his partner, CEO Leonid Friedland, whom Suzy Menkes, the fashion critic for the International Herald Tribune, once dubbed “one of the most powerful men in fashion.” (The group owns the TSUM department store in Moscow, the Barvikha Luxury Village in a Moscow suburb, and sells brands ranging from Gucci to Maserati—all of which has helped Phillips establish a firm foothold in the Russian contemporary art market.) Spurred by the infusion of new cash, Phillips has introduced cocktails and club music into its auction previews, marketed design to contemporary art collectors, and held themed auctions like BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) as a way to capitalize on emerging markets.

The house has also drawn the ire of a number of gallery owners for bringing works by young artists to the auction block. Last fall, 27-year-old painter Jacob Kassay made headlines after Phillips sold one of his canvases, first completed and shown in 2009, for $86,500, more than 10 times its high estimate. Fierce bidding for another Kassay painting during Phillips’s evening sale this past May, just six months later, brought a price of $290,500. (His work sells for $20,000 to $40,000 on the primary market, though there’s a waiting list; at auction, if they’re willing to pay top dollar, bidders can jump the line.) Tapping artists for the secondary market early in their careers (what de Pury called “buying tomorrow’s blue-chip artists today”) has made him unpopular with several dealers, who see the practice as potentially damaging to the long-term development of talent. De Pury, however—while acknowledging the gallery’s role in nurturing artists and placing their work in the right hands—insisted that “those galleries that try to control it…well, that’s ultimately completely counterproductive, because you also need works of an artist to come regularly onto the market for the confidence level to develop. A work’s standing in the auction market is the most concrete marker of its value.”

Which isn’t to say that a work’s standing doesn’t benefit from a little presale razzle-dazzle. Last November, in a first for the auction world, Phillips invited an outside expert—the well-known dealer Philippe Ségalot—to guest-curate an evening contemporary sale. The so-called Carte Blanche initiative kicked off the opening of Phillips’s uptown salesroom at Park Avenue and 57th Street (Phillips also runs a space in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District) and featured Maurizio Cattelan’s lifelike bust of Stephanie Seymour, its hair styled for the auction by Frédéric Fekkai. At Phillips’s evening sale in New York this past May, it was Liz Taylor’s turn in the spotlight: When de Pury brought the hammer down on Warhol’s 1963 Liz #5 (Early Colored Liz), its price was $27 million, in line with its estimate.

“It’s a high-wire act,” de Pury told me the morning after the sale, which overall had drawn tepid bidding but totaled a respectable $94.8 million. “I still get nervous before each one.” We were having breakfast at the Pierre, one of the many hotels that for years served as de Pury’s home prior to his recent marriage. Though known for a high-octane sales style peppered with humor, de Pury conceded that he spends the hours before an auction in solitude, away from the gallery, carefully studying both the salesroom seating chart and each work in the catalog so as to focus “on who the likely contenders might be,” he said. “By the time you get to the podium, you have a pretty good reading of how it might go. But, of course, if you knew, you wouldn’t need the auction.” The most important works, he said, are placed early in the sale but never back-to-back, “because people are still talking about the big one that was just sold and not fully concentrated. So you have to have your high points and slower points and create a rhythm.”

The best auctioneers, said Taschen, “are like racehorses. They have to build up to the moment and play with ease, so that it looks like it all comes together naturally. But it doesn’t.” Asked to characterize his approach, de Pury mentioned legendary Sotheby’s auctioneer Peter Wilson, whose style, he said, was “the exact opposite” of his own. “He was incredibly quiet, speaking with a soft voice, so it was like he was allowing you to take part in something very exclusive.”

Growing up in Basel the youngest son of a Swiss pharmaceutical executive and his wife, who practiced ikebana (Japanese flower arranging), de Pury had hoped to become an artist. But after a trip to New York to show his portfolio to the galleries with the biggest ads in The New York Times—Knoedler and Leo Castelli—he lost heart, he said, when they promptly turned him down. (This past January, though, an exhibition of his photographs—a series of abstract images snapped on his travels—opened at the chic Paris boutique Colette.) He worked at Sotheby’s early in his career but made his name in the Eighties as curator for Baron Heinrich “Heini” Thyssen-Bornemisza, who, as the biggest buyer of the day “had first crack at anything that was available,” de Pury recalled. At Thyssen’s Villa Favorita in Lugano, Switzerland, de Pury not only developed his formidable network but also negotiated the first pre-Glasnost loan of works to the West from the Pushkin and Hermitage museums when they swapped—picture for picture—40 paintings for Thyssen’s collection in 1983. Returning to Sotheby’s in 1986, de Pury went on to become its chairman in Europe before setting up his own successful dealership with Daniella Luxembourg. In 2000, the two agreed to a merger with Phillips, then owned by Bernard Arnault’s LVMH. The relationship, however, didn’t flourish; de Pury ultimately took a majority share when Luxembourg returned to private dealing.

De Pury, holding daughter Diane Delphine, and wife Michaela at a private viewing of Linda McCartney’s Life in Photographs.

His romance with Neumeister, his second wife, came as a surprise to both of them. They’d been working together closely for eight years, “and I’d matched him up with girlfriends,” she said, when one day in Moscow, he recalled, “I suddenly looked at her with totally different eyes. Then we thought we’d be very adult about it as if nothing happened. And then every time I saw Michaela, it would start again, until I realized that the person I loved had been in front of me all this time.”

“I was afraid, but I married him because I thought even if it’s for 10 days, it’s worth it,” said Michaela, 41, a tall, angular blonde from a Munich auctioneering family who holds a doctorate in art history. Her wedding present to her husband was the artist duo Elmgreen and Dragset’s Second Marriage (2008), two sinks with their pipes tied. Until the de Purys announced their marriage via e-mail, not even their personal assistants knew about the relationship. “The last thing I ever thought I’d do is marry again,” said de Pury, whose love life was the talk of the art world in 2003 after he installed as CEO—and later was believed to have forced out—his then-girlfriend, millionaire publisher Louise MacBain. “And then starting a family again,” added de Pury, who has four grown children. “It’s a wonderful time.”

Along with their 10-month-old daughter, Diane Delphine—to whom her mother speaks in German and her father in French—the couple now live in London’s Mayfair, where their upstairs neighbors include Rupert and Wendi Murdoch. But the de Purys are rarely home for long, and though they plan to fill their apartment with “a completely funky mix,” said Michaela—ranging from a Gothic Madonna and a Franz West table to “a lot of cutting-edge art”—“everything is pretty much in bubble wrap on the floor.” (De Pury’s skateboard collection is relegated to his London office.) As have many of their friends, Alexander Gilkes, a young Phillips auctioneer groomed by de Pury, called them “a formidable force,” and added: “It’s 24-hour art with them. Simon’s the perfect door opener, and Michaela’s the perfect door closer.”

“It’s a kind of traveling circus, and we pitch a tent where we can,” de Pury told me in June, when we met in Zurich en route to the home of Maja Hoffmann, the Swiss über collector whose annual kickoff party for Art Basel is a much coveted invitation. De Pury was to officiate at the night’s charity auction to benefit Zurich’s Kunsthalle. He and Michaela had just arrived from Berlin via billionaire Nicolas Berggruen’s plane, and the next morning would fly to Windsor Castle in time to see a friend installed as a Knight of the Garter by the Queen and assorted Royals, among them Kate Middleton, the newly minted Duchess of Cambridge. As they led me through Hoffmann’s glass-encased home, a Marcel Breuer gem, and across its sprawling lakeside lawn, some of it tented for dinner, they worked the high-wattage crowd, unable to move two paces without bumping into the likes of Larry Gagosian, John Baldessari, Elizabeth Peyton, Jay Jopling, and the recently reconciled Peter Brant and Stephanie Seymour.

Before the night was over, de Pury had whipped the art tribe into giddiness as he prodded the guests to give it up for the lots on offer: a sketch of any house by Rem Koolhaas, a visit with Andreas Gursky in his studio, a family album deconstructed and transformed by Baldessari. “We’re up to zirty thousand—you can bid against yourself!” de Pury joked at one point before bringing the hammer down on the winning buyer’s dinner plate.

Two days later he was among the influential players previewing Art Basel, the king of art fairs, hoping to get a jump on the action. Three hundred galleries were showing work by some 2,500 artists, an estimated $1.75 billion worth of art. “I’m the extended eyes of the collectors,” de Pury told me as we passed Naomi Campbell and Eli Broad, explaining that he sends JPEGs to prized collectors who prefer to stay home. Already, his mind was on Phillips’s first sale in Hong Kong, planned for 2012, the new buyers emerging from Asia, the Eastern Bloc, and Brazil, and on the growing inclination of the rich to look at art as a safe investment, not just a pleasure. Then, of course, there was art to see: He suggested that I check out the new silver paintings by Kassay and directed my attention to neobaroque busts by Barry X Ball, a 1996 black and white painting by Christopher Wool, and Wade Guyton’s 2011 Untitled, all the while texting furiously and greeting colleagues in many languages. “For some collectors, it’s when a work is new that it hits their radar,” he explained. “For others, when it hits one million.” I began to ask about his goals, but he held up his hand. “I never think in terms of goals,” he said. “You just have to be attuned to what’s being offered, to which artists are emerging. It’s the same with music: You have to follow it all. You can’t stop.”

Testino, Moss, and de Pury: Retna LTD.; wedding: Kevin Tachman; ee Pury at RXArt Party: Billy Farrell Agency; Work of Art: courtesy of Bravo. De pury with wife and daughter: Getty Images