The Change Agent

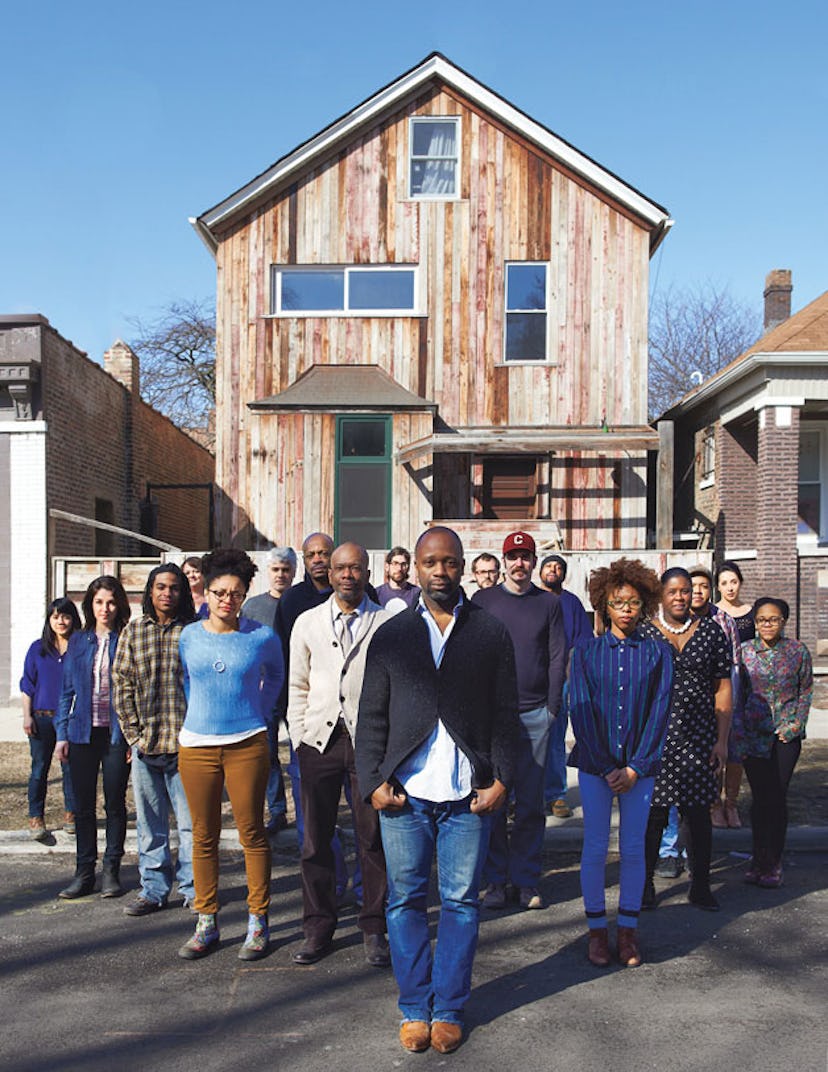

Theaster Gates is constructing a brilliant art career—and transforming his Chicago neighborhood—one salvaged building at a time.

The first time Theaster Gates showed his work at NADA Miami during Art Basel Miami Beach, in December 2009, he was an unknown artist from Chicago’s South Side. He’d never had formal representation, so when the curator Francesco Bonami invited him to participate in the 2010 Whitney Museum’s Biennial, Gates approached the Chicago gallerist Kavi Gupta for help. The Biennial was three months away, and Gupta thought it wise to “position” Gates in advance of his New York spotlight. So Gupta took shoe-shine stands to Miami that Gates had made using clapboard siding from a building he had restored. Gates’s towering wooden thrones were modeled after those at Shine King, a storied West Side shoe-shine joint where preachers and cops sit alongside NBA stars. The sculptures were powerful in their own right, but once Gates arrived in Miami, he decided on the spur of the moment to animate them. As high-flying patrons wandered through the fair, he invited them to take a seat—and then began shining their shoes. Crowds formed to watch him, and collectors quickly learned his name. The chairs sold out, with the Chicago arts patron Larry Fields paying around $12,000 for one upholstered in red and yellow vinyl.

“Those performances were about me inviting white people to sit on these thrones,” says Gates, whose ascent through the art world has been brisk, even by its warp-speed standards. “It’s one thing when a seemingly unconscious brother is shining your shoes. But what about when it’s a very conscious Theaster? And instead of asking, ‘Where you flying to, boss?’ and shit, I’m asking, ‘How are you enjoying the art fair? Do you plan to buy things? What’s your budget? Where are your shoes from?’ ” The point, he says, was to explore the idea that “certain forms of labor are associated with certain kinds of people—and to blow that up.”

It’s a blustery day in Chicago, and Gates, 39, is in his living room on the second floor of the Black Cinema House, just one of the buildings he has revived on Dorchester Avenue in Greater Grand Crossing, a once genteel neighborhood near the University of Chicago, now marred by empty lots and boarded-up foreclosed homes. Gates has a shaved head, a grizzled beard, and dark brown eyes that quickly take your measure. His thick hand-knit sweater accentuates his burly torso. As he pours tea into handcrafted sake cups, he explains that the Dorchester Projects, the name he’s given to the spaces he’s reclaimed, respects buildings as found objects.

On the first floor of Black Cinema House is a movie theater he created so the Chicago Film Archives could screen films about African-American culture and by artists of color. The redwood around the doors and windows was rescued from a water tower, and the green walls of a guest room are, in fact, chalkboards from an elementary school. Hanging on a wall is a series of framed tapestries by Gates, made from fire hoses referencing those used by the police to disperse civil rights protestors in Alabama in 1963. Across the street, a house that Gates salvaged is now a haven for the mostly black neighborhood, as well as an informal archive for 8,000 LPs and 14,000 architecture books from shops that went out of business and 60,000 glass art-history slides discarded by the University of Chicago, where Gates is both an urban planner and an arts administrator. Pottery produced by Gates lines the shelves in the kitchen, where communal meals are regularly served. When Gates gutted the building, he turned the salvaged materials into tables, benches, and display cases, training local laborers to build them.

Gates, in March, in front of his tar painting Prime Real Estate, 2013, photograph Jason Schmidt.

Gates, of course, is hardly alone in turning scrap into gold or in producing works charged with social commentary. What sets him apart is his ability to operate as both an artist and an urban planner who uses art as a catalyst to effect economic and social change. Drawing on his background in sculpture, performance, ceramics, cultural planning, and community activism, he mines the detritus of bleak neighborhoods, the touchstones of black history, and the symbols of black protest, creating jobs and vitality in spaces given up for lost. “My task is just seeing what can get reactivated,” he says.

He’s also committed to staying in his neighborhood. The buildings he improves are not sold off so that Gates can move to New York or Berlin; they are investments in the community in which he continues to live and participate. Proceeds from the works he sells are funneled into his next projects. “He creates value out of dysfunctional situations,” says his friend David Adjaye, the architect of the forthcoming National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. “And he’s capitalizing the whole thing. He’s created his own ecology.” Gates’s latest undertaking is a 1923 bank building just four blocks away. It will be “one of the most significant cultural anchors on the South Side, if not the city,” he says as we tour the 20,000-square-foot Deco gem. “It’s a potent symbol, the idea of a bank that doesn’t work. It’s the biggest found object, the biggest Lazarus I’ve tackled.”

His vision for the building includes a culinary training institute, a soul food restaurant, exhibition and performance spaces, offices for arts groups, and a library housing books by black authors and magazines from the collection of John H. Johnson, the founder of Ebony and Jet. As we stand on the mezzanine, Gates gazes down into the vast atrium. “It reminds me of some kind of old-town brothel, you know?” he says. “It’s this architecture you don’t have access to unless you’re part of this or that arts club. And the idea that an artist might also be able to think about a new kind of museum or place where historical objects land—and do it better than people who think about historical objects all the time—is exciting to me.”

The first step was to save the bank from demolition. The city of Chicago awarded the building to Gates with the agreement that he is responsible for its restoration. “Now people want to know ‘Where is he going to get the money? Is he in over his head? Will he fall on his face?’ ” Gates says. “We don’t know yet. And so it’s like a miniseries that plays out in real time.”

Gates is an intent listener who manages to get a lot of other things done in the course of a conversation. He has just come back from the World Economic Forum, in Davos, Switzerland, where he gave several talks about his work, “so I’m catching up,” he tells me as he folds laundry, scrubs the kitchen counter, exchanges updates when members of his team appear, and fields calls from his father and then from a university colleague with whom he discusses a new arts incubator he is directing. “Everybody’s struck by how much he can do at once,” Kate Hadley Williams, his studio manager, says. “His belief that it can all happen allows everybody else on his team to believe in themselves, and make it happen.”

He’s certainly a deft networker who knows how to leverage his clout in many spheres. Gates has drawn foundations, developers such as the Pritzker family, and Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel into his orbit. “His brilliance kind of sneaks up on you,” says Johnson Publishing Company CEO Desirée Rogers; the former White House social secretary is a friend and fellow thrift-shop adventurer. “Interesting is an understatement. He loves to throw people together. He’s already seen the common thread, and if you don’t discover it quickly enough, he’ll egg you on.”

The youngest of nine children and the only boy, Gates tarred roofs with his father growing up on Chicago’s West Side. Each summer, he was sent alone by bus to rural Mississippi to work on his uncle’s farm. It wasn’t until he had to cross the city to attend middle school that he had contact with white kids. Gates cut his hair to fit in. “I felt I was in someone else’s world,” he says. “And I felt really apologetic about it until I realized: I’m as smart as or smarter than these kids. It’s a pretty big world. Maybe it’s my world. Wherever I am, I have a right to be.”

When he was 15 years old and a high school sophomore, he rented an apartment from his parents, who’d bought a building down the block from their home. He paid rent by working odd jobs. “I had a thing for space,” he says. “I wanted my own interesting place.” He can still recall how he tore down walls and “tricked out” the bathroom with the help of a mosaic artist. By then, Gates was the choir director at the New Cedar Grove Missionary Baptist Church; his mother hoped he’d become a preacher. “I’ve always believed in the power of music—songs have the capacity to do things that objects can’t, to convey a particular kind of emotion.” Gates rehearsed with the choir three days a week and memorized scripture, trying “to balance a healthy appetite for fun and worldly pleasure with an earnest relationship with God. By college, I was chaplain for my historically black fraternity.”

With an eye toward improving urban living conditions through work in the church, he attended Iowa State University to study urban planning and ceramics, which he’d discovered in college, and then went on to the University of Cape Town in South Africa for religious studies and fine arts. He returned home and took a job as an arts planner for the Chicago Transit Authority, acting as liaison between artists and the city to put art in train stations. But he grew frustrated that artists were rarely given much of a leading role and eventually moved to the University of Chicago, to be coordinator of arts programming. He started a gospel band, the Black Monks of Mississippi, which combines black spirituals with Buddhist chants, and got involved in the city’s performance scene.

Gates was also making pottery, though he was unsure of how it fit in with his larger aims. Then, in 2007, he developed the Plate Convergences project for which he invited an eclectic mix of guests to a dinner in honor of a fictitious mentor he named Yamaguchi. Gates’s protagonist was a Japanese ceramist who had married a black civil rights activist and founded an arts center in Mississippi where people discussed race and inequity while dining off Yamaguchi-crafted plates. Over Gates’s staged Japanese soul food dinners at the Hyde Park Art Center, guests became fascinated by his supposed Yamaguchi bowls and their lore, and by a young college student whom Gates had asked to “play” Yamaguchi’s son.

Soon Gates dropped his fictional alter ego, openly making “soul food ware” based on Japanese tea pottery. “When you take the time to make a ritual, then people value the experience,” he tells me. “They value the utensils of that experience, and they value the people they meet. So over the years, I’ve become really sensitive to who’s coming to dinner and why they’re coming. My hope is that these different folk who meet each other could be friends. And friendship builds a radical encounter. I understood from an early age that dinner could do work besides feeding people.”

Six years later, his series of dinners for the Smart Museum of Art’s 2012 exhibition “Feast: Radical Hospitality in Contemporary Art” drew billionaire developers, European curators, and neighbors down the street to his table on Dorchester. There was food, conversation, and a jam with the Monks. Once, Gates was greeting guests when a drive-by shooting erupted. “We had to dive down,” says Gupta, his Chicago dealer—but dinner went on. “Theaster knows some people feel odd coming to the South Side. But that’s the reality of life on his street, and he plays with that.”

Last summer, Gates’s Dorchester home found its way across the Atlantic. For 12 Ballads for Huguenot House, he renovated a dilapidated building in Kassel, Germany, using materials salvaged from the gutting of Black Cinema House. The installation made him the breakout star of Documenta, Kassel’s prestigious international art survey. Gates and a crew from Chicago worked with local artisans to furnish some of the rooms, while in others, he and the Monks performed live or screened videos of themselves playing in the Chicago house. In this way, Gates created a sort of conversation between the two places.

“I was practically crying as I walked through,” recalls Adjaye, who began his career designing homes for artists in London’s pre-gentrified East End. “It was the most extraordinary work I’d seen in a very long time. Documenta cemented his arrival in the world as a major star. It was unanimously seen as one of those profound moments.”

This month, vestiges of 12 Ballads for Huguenot House make the return trip to Chicago in Gates’s new installation, 13th Ballad, opening May 18 at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA). “The search for the next hot thing is something Theaster has very intelligently jujitsu’d,” says Madeleine Grynsztejn, the MCA’s director. “He’d be doing what he’s doing regardless of whether the art world paid attention. His work resonates with a kind of desire to touch ground and renegotiate with something real. We’re coming out of a period that was very glossy. His artwork grounds us in, rather than separates us from, the world.”

Surely it’s no coincidence that Gates’s career is rooted in Barack Obama’s hometown, where the president first worked as a community organizer. Gates is part of a generation engaged in what has come to be called “social practice”: art that flourishes outside galleries and museums and welcomes all, opening dialogues with those who live beyond its precincts. Encompassing social service, community building, object-making, and real-time discussion around economic inequity, it’s social activism through art-making. Though the movement is well established in Europe and South America, it has only recently been on the rise in the United States and, not incidentally, just as the art market has shot to previously unseen levels. Works of this kind run the gamut from artist-run, city-funded programs in San Francisco that turn vacant lots into gardens to New York artist Tania Bruguera’s programs that help immigrants. “The work is painful—that’s a critical aspect of it,” Grynsztejn says. “But it’s transformative, and that makes it real as opposed to metaphorical.”

Gates says he still lives “between classes and cultural opportunities. I understand that money isn’t the solution to everything.” But now he has ready access to it. In 2010, before his Whitney debut, his works sold for $10,000; these days his larger installations go for $150,000. He recently posed for a Burberry ad and, in late 2011, after being courted by a multitude of dealers, surprised many when he joined the juggernaut London gallery White Cube, the emblem of the hard-driving commercial art world, the very name of which seems the antithesis of everything he stands for. (Gates is co-represented by Gupta and White Cube.) But Gates isn’t simply falling into step with how blue chip galleries present work; he consciously subverts the systems that embrace him. He is “purposeful”—a word that crops up often in his conversation. “There was something poetic about the gallery’s bad-boy nature,” Gates says of White Cube. “My gut said, I can have fun with this. Could I exploit the exploiter? Could I leverage this 30,000-square-foot commercial gallery and offer nothing for sale in 20,000 square feet of it? You take from it what you will. I just needed a big machine.”

“My Labor Is My Protest,” Gates’s debut show there last fall, included his fire-hose readymades and a series of paintings he created with his father using his father’s tar kettle. Gates also built an enormous functioning library, featuring a selection from the Johnson Publishing Company archives’ magazines and books on black history alongside a vintage makeup counter displaying cosmetics from Fashion Fair, the first company to produce upscale beauty products for the black consumer. His showstopper was Raising Goliath, a red fire truck suspended midair and counterbalanced via a pulley system by an 8- by 32-foot metal container crammed with bound volumes of Ebony, Jet, and other magazines. The work alluded to race riots and the means used to quash them, the ways in which Gates’s father labored with fire to make tar, and how Gates leverages black history and culture as a vehicle for transformation.

Gates was joined at White Cube by the Monks, who sang laments about manual labor. Adjaye recalls him “in the halo of the White Cube space, and people coming in their gowns, and here is Theaster throwing down his blues. People were not quite sure what he was doing, whether it was a joke or it was real. But for Theaster, it’s real. He’s really enacting a spiritual moment.” During last fall’s Frieze Art Fair in London, Gates performed a set at Ronnie Scott’s famous jazz club one night; Miuccia Prada, Evgeny Lebedev, Lily Cole, and a who’s who of the London art world turned out to see him. “He’s one of those artists who work hard and party hard,” says his friend Naomi Beckwith, a curator at the MCA who met him in 2008. “He doesn’t sleep much.” Last summer, the two traveled from Documenta to Cap Ferrat, France, to attend the 50th-birthday party of Marty Nesbitt, a Chicago businessman who collects Gates’s work and is one of President Obama’s closest friends. (Not long after, Gates and the Monks performed for Obama on his birthday.) “You could not get Theaster off the dance floor,” Beckwith says. “He had these very respectable ladies doing all sorts of weird backbends. He’s a charming flirt.”

While he bankrolls his civic ambitions, Gates is converting a 25,000-square-foot abandoned Anheuser-Busch distribution center near his home into his new studio. There will be exhibition and performance spaces, and it’s likely he’ll bypass the gallery system altogether when it suits him and invite the public there. The day I visit, stuff is piled everywhere: crates of wooden moldings, stacks of pottery, classroom chairs, an enormous globe. A hoarder’s palace. Gates’s team has congregated to sort through it all and to prepare 13th Ballad. The work will take the form of an enormous double cross, backlit in neon and fitted with interior boxes holding relics from the house in Kassel. Church pews will fill the museum’s atrium, and musical performances will riff on themes of migration. Gates leads me to an interior room, where soft light spills through an open skylight. It’s 20 degrees and we can see our breath. “My sanctuary,” he says. “I don’t let people in here yet.” He is still considering how much of the derelict building he will leave untouched and figuring out which partners he needs to make things work. And in September, he will show new work at White Cube’s galleries in Hong Kong and São Paulo. “There are days when I feel I can really drive this ship, and then there are days when I feel defeated because there are too many things to be in charge of,” he acknowledges. “So it just has to be a game. You know, I have to just say, ‘This is all kind of moving fun things around. Do one thing at a time and don’t be so crazy about it all. Miller time.’ ”