The Hermès Lumière Necklace Hides a Shining Secret in the Shadows

Pierre Hardy, who is known for his distinctive brand of stealth glamour, is in a philosophical mood. The creative director for Hermès shoes and jewelry believes there’s never been a better time to look beyond the obvious and embrace one’s esoteric side. “It’s definitely a moment for contemplation,” he observes, “to pay attention to everything that’s happening in the world.”

Hardy, who joined Hermès in 1990, is musing about his latest high-jewelry collection, Les Jeux de l’Ombre, comprising 53 pieces inspired in part by the moody 16th- and 17th-century chiaroscuros of Caravaggio. A former dancer, the Paris-born Hardy explains that the dramatic collection, his seventh since he launched Haute Bijouterie for the luxury house in 2010, forms a pas de deux between “the two sides of Hermès.”

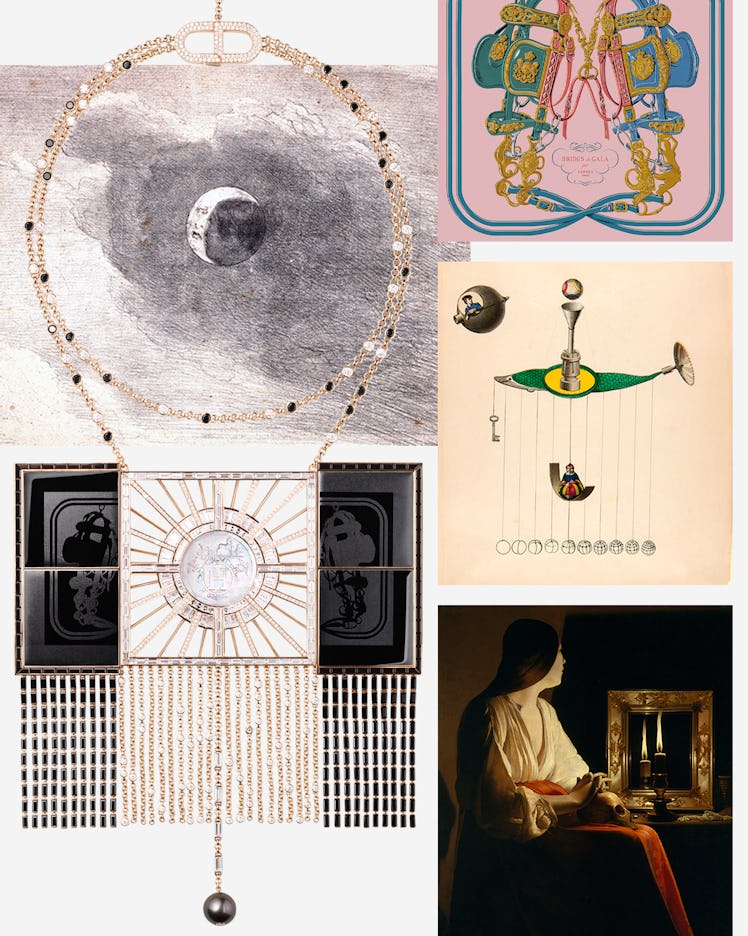

The Hermès Grand Soleil Triptyques Lumière necklace, which evokes the interplay of planetary bodies.

Georges de La Tour’s chiaroscuro painting The Penitent Magdalen, circa 1640.

Nowhere is this duality more apparent than in the standout Lumière necklace, a triptych light box with sliding black enamel panels engraved with the Brides de Gala motif, one of Hermès’s most iconic scarf prints, which open to reveal a sun medallion. Borrowing from Caravaggio’s idea that shadows contain an inner light, and designed to be worn either closed or open, Lumière sets the stage for the passage from darkness to brilliance, the outer panels with black spinels giving way to rose gold set with diamonds and pink mother-of-pearl.

Great Eclipse of 1836, a lithograph published by T. McLean.

Though Hardy is not usually given to overt narrative in his designs, the entire collection, he says, tells an overarching story about the contrasts found in nature. The triptych necklace alludes to the alignment of celestial objects that occurs during lunar and solar eclipses. But the Lumière is also a nod to olde-worlde stage machinery and contraptions. “It’s the first time I’ve experimented with jewelry that moves,” Hardy says. Some of the pieces in the collection bring to mind the sumptuous automatons favored by 17th-century aristocrats and now prized by watch and jewelry collectors. “We used an intricate watchmaking mechanism, but it’s exactly the same concept as they used to have in theaters in the 17th century to make gods or angels appear onstage.”

Hermès’s Brides de Gala scarf.

Not that Hardy is all about descending deities and cosmic phenomena. For the perennially cheery designer, his foray into the obscure offers a portal into a world of possibility. “Everyone has been out walking at night and tried to outrun their shadow,” he says. “You can’t; it’s bigger than you and a part of you. We need to embrace our shadow. It’s like a ghost, but a playful one.”

Besides, he adds, it would be boring if everything were always shiny and sparkling. “The beauty of jewelry,” he surmises, “is when it transcends materiality, value, and price and instead makes you dream and think. Either there is magic or there isn’t.”

Joseph Cornell’s Untitled, 1930–1940, a mixed-media engraving depicting celestial objects.

This article was originally published on