Alessandro Michele: The New Romantic

Alessandro Michele’s vision for Gucci is more eclectic magpie than sexed-up glamazon. Following him to China for a museum exhibition, David Amsden tracks the designer’s fairy-tale ascent.

On a Friday evening in late October, Alessandro Michele, the creative director of Gucci, was inside the Minsheng Art Museum, in Shanghai, sounding like a philosopher struggling to make sense of the world around him. “What is contemporary?” he asked in his lilting Italian accent. “This word, what does it mean? Do you know? I do not know. Does anybody?” Michele speaks almost exclusively in such splintery abstractions, whether discussing his childhood in Rome, where he continues to live and work, or his vision for Gucci, where, since his appointment in January, he has been on a freewheeling crusade to recast a label known for its sex-and-money fantasy of luxury in a more whimsical, gender-ambiguous light. At the moment, however, Michele was referring concretely to the three-dimensional space of the museum, where a party was under way for an exhibition titled “No Longer/Not Yet.” He had curated the show with Katie Grand, the editor of Love, the English biannual fashion magazine. “We gave this question of ‘What is contemporary?’ to the artists, and let them do whatever they wanted,” Michele remarked. “I did not want any rules, since rules create endings, and I prefer beginnings.”

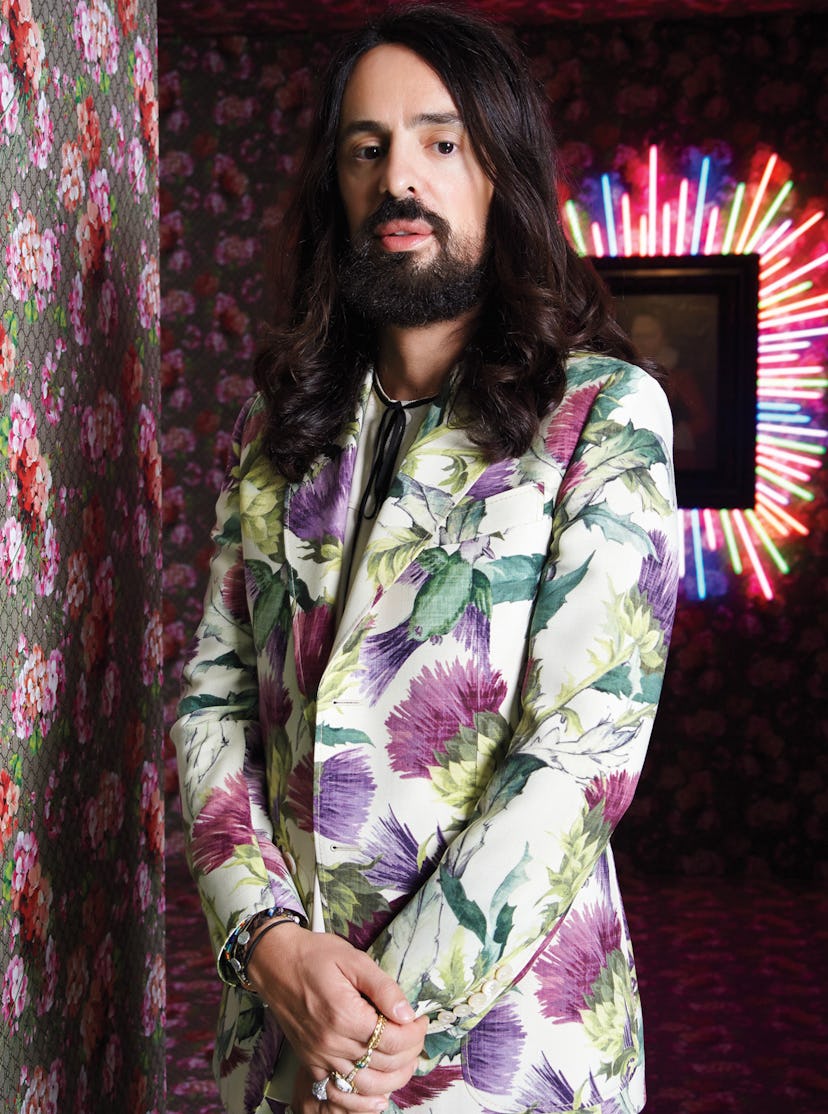

Dressed in a floral-print suit of his own design, which he believes should be worn by both men and women, his long brown hair framing his bearded face, and his hands festooned in 19th-century rings, Michele came across as the sort of bookish eccentric you’d encounter wandering in an ashram rather than sitting at the top of a $3.9 billion fashion empire. The seeds for the Shanghai exhibition had been germinating since February, shortly after he showed his fall women’s wear collection in Milan. Though technically not his first show as creative director—he had put together a fall men’s wear collection in a harried five days—the outing introduced the exuberant, nerdy sensuality that Michele has been mining at Gucci ever since. The brand’s signature snaffle-bit loafers came lined with shaggy fur, like decadent bedroom slippers; pleated skirts fluttered in strong ’70s shades; and metallic dresses also sported fur—in pale pink, on the cuffs. Praised as a much needed shot of adrenaline to a label still ossified in the hard-edged mold of Tom Ford, the collection was the by-product of Michele’s wrestling with the definition of contemporary. Bookending the show’s notes, for instance, were quotes from two philosophers: the Italian Giorgio Agamben and his French counterpart, Roland Barthes, who stated, “The contemporary is the untimely.” The same quotes appeared on the walls of the Shanghai museum.

Art, like fashion, can give physical shape to abstract concepts, grounding the kooky and ephemeral in something tangible. Energized by the fall show, Michele reached out to Grand soon after about the idea of extending the themes to an exhibition—a fun, sly way of inviting the world to rethink its perception of Gucci. “It was all very natural, which is how I like things,” said Michele, who exudes the curiosity of a child in an industry where iciness is often mistaken for sophistication. “It was like we were compiling a list of the people we love in order to throw a party.” Grand, making the rounds in the museum in one of Michele’s creations, a men’s jacquard coat, marveled at how quickly the exhibition had come together. “Just a few days ago, this was basically a warehouse,” she said of the space, which had been transformed into a series of rooms painted in colors ranging from bright pink to coal black, with dropped ceilings to foster intimacy.

As a rapidly expanding market for luxury goods, China is a fitting location for a bit of subversive brand refurbishment. Michele, however, discussed the project in a context that was far more romantic than calculating. “Asia means a lot, yes, but I’m not talking about the market,” he said. “The market is going in a very strange way everywhere, and, thankfully, that’s not my job to understand.” He offered the wily grin of a designer who, at least for the time being, has been given the mandate to do what he wants and let others worry about the numbers. He had spent the previous afternoon getting happily lost around Shanghai, a city with the hallucinatory, steroidal feel of a metropolis capable of reinventing itself every 15 minutes, and was clearly in awe of his surroundings. “Twenty-three million people live here!” he said, his brown eyes widening. “How is that possible? I really love this kind of landscape. It’s like a masterpiece in crazy!”

As he spoke, the museum was filling with members of the press, assorted style ambassadors, and a few of the show’s seven participating artists, each of whom had been given a room in which to interpret the notion of contemporary. The results were playful and provocative, with references to Gucci coming in the form of winks rather than the clumsy, corporate gloss that can give such affairs a cynical undercurrent. The British photographer Nigel Shafran, for instance, displayed a series of stark, behind-the-scenes shots from the making of Michele’s fall women’s collection, each illuminating typically shielded corners of fashion: seamstresses working in a fluorescent-lit room; a security guard manning empty rolling racks inside Gucci’s Milan headquarters; the cords of hair dryers and hair straighteners looking like dead weeds on a foldout table. Michele, whose capacity for enthusiasm is by all accounts limitless, reveled in the celebration of the mundane. “I understand that people want to see just the posh side of fashion, but fashion is a lot of work,” he had remarked at a talk about the exhibition earlier in the day, explaining that the seemingly humdrum images were, in fact, the documentation of a kind of revolution. “When I started to work at Gucci,” he told the audience, “I tried literally to destroy everything.”

Most of the art, however, had no direct connection to fashion. Jenny Holzer had created a mesmerizing light-strip sculpture that hung from the ceiling and delivered elliptical phrases in English and Chinese on an eight-hour loop. Rachel Feinstein offered a sculpture based on a drawing her 10-year-old son had made, which she discovered crumpled in the trash. Cao Fei, a Chinese multimedia artist, had transformed her room into a somewhat dystopian world, with wall-to-wall carpeting (a Gucci confection in purple, white, and green) giving way to a sunken crater at the center, in which a series of Roombas, the robotic vacuum machines, circled and collided at random. A video of rural land being cleared for development was projected onto one of the walls, and the cumulative effect was both haunting and unsubtly anticommercial. “Like this show, China is a country that exists right between ‘no longer’ and ‘not yet,’ ” Cao explained.

Michele had spent much of the past few days in the museum, walking the rooms with Grand and offering last-minute tweaks up until late the previous night. “I was a little bit scared by this idea,” he said. “Sometimes this whole thing, not just this show but this brand, it can be almost too much, you know?” He paused, taking in a deep, exaggerated breath to convey that, contrary to his untroubled disposition, his job is not without moments of paralyzing panic. “But then when I went to sleep, I was like a baby, so I knew it worked.”

He was especially thrilled with the contribution of Helen Downie, a British artist who goes by the moniker Unskilled Worker and who started painting only recently. She had created 43 works for the event, ethereal portraits of people important to her, some fictional or imaginary, all wearing garments from Michele’s fall collection. They were hung salon-style on glossy crimson walls. “She has some of my sensibility,” said Michele, who had discovered her work on Instagram, a platform he talked about with zeal. “I’m not scared about that kind of thing,” he said. “It’s just another language, you know?”

Downie, for her part, seemed hardly able to process the reality of the evening. “This is the first time people have seen my work outside of Instagram,” she said, shaking her head. “Two and a half years ago, I wasn’t even painting, and now I’m here in Shanghai? With Gucci? I mean…what?!”

Michele delighted in the sentiment. “My story, too, it’s quite unbelievable for me,” he said. “It’s like a fairy tale.”

Three weeks earlier, Michele was seated in his office in Milan. Fashion Week was in full swing; he had opened the proceedings with a lavish spectacle two days prior, staging his spring collection in a former railway depot. With its emphasis on frumpy skirts, geeky eyewear, and vintage quirk, the show was hailed as a blockbuster—a deeper, more kaleidoscopic exploration of the new Gucci aesthetic he had introduced in February. While visibly exhausted, Michele was relieved to savor a moment of calm after weeks of chaos. “I’m in charge, but also I’m not,” he said, describing the importance of maintaining a sense of innocence in his new role. “If tomorrow everything is gone—this is okay. Like, if you love someone, and you are doing everything on one night, but you don’t know about the day after? That’s the beauty. That’s the way to work.”

Much as such monologues reinforce the idea that he is the inhabitant of a fairy tale, the path to arriving here has not been without drama and despair. Michele had worked at Gucci for 12 years before being named creative director, first under Ford, and then as head of accessories for Frida Giannini, whom he replaced in January. “I never wanted to be a creative director,” he said. “I have a big respect for my life, and this job can become your life.” In fact, over the past two years, Michele had grown increasingly disillusioned with his job. While the sex-centric vision created by Ford during his reign, from 1994 to 2004, had turned a nearly bankrupt company into the behemoth it is today, Michele, like many fashion observers, felt as if Gucci had become a brand trying to capture the imagination of a consumer who no longer existed. “I was really sad,” he said. “I love this company like I love my house. But when you understand you can’t go ahead, you have to leave.”

As he was planning his exit, the company entered a period of turmoil. With sales slumping, Giannini was pushed out along with her partner, then-CEO Patrizio di Marco. When the new CEO, Marco Bizzarri, came on board, he asked to meet Michele. “I suppose he wanted to make sure I was happy,” Michele said, seated on a tattered velvet couch that was among his office’s few furnishings. (“I’m still redoing the space,” he noted. “Before, it was very Tom—shiny black and fake marble.”) While he had thought the conversation with Bizzarri would serve as the beginning of the end of his time at Gucci, Michele found himself engaged in fervent discussion about the brand: where it had been, where it could go. “Tom worked with this idea that sexiness was like a god, something you could adore and wanted to be,” Michele said. “But what does a girl want to be now? That goddess of Tom has changed. She wants to be the goddess of the streets, a goddess of tenderness. Maybe even she wants to be completely ambiguous.”

Without realizing it, the casual chat had become a job interview, and Michele was given the opportunity to be creative director shortly thereafter. “What I thought was going to be the beginning of a breakup,” he noted, “became instead a marriage.” After years of European houses turning to outside wunderkinds to revive their brands, Michele’s appointment represented a new model, the idea that a veteran with deep knowledge of a brand may be best suited to reinvent it. “I’m playing in my house, so it’s easier to be confident,” Michele said.

At the Shanghai exhibition, Michele was both a curator and a featured artist. For his contribution, he had converted one of the museum’s rooms into a surreal landscape: a tranquil, brightly lit space wallpapered in the same tropical print that adorns the new Gucci bags and clothes. The floor was mirrored, and in the back of the room, like a jewel box, was another room, its exterior walls also mirrored, making the small space feel infinite (and ideal, judging from those gathered, for capturing selfies). A door to this room within the room opened to reveal an interior plastered in a rich pink paper, Gucci’s trademark interlocking Gs barely visible amid the bursts of flowers. On the wall, framed in neon, was a reproduction of a Tudor painting that normally hangs in Michele’s apartment in Rome: a figure clad in a red gown with a stiff ruffled collar. What at first seemed to be a portrait of a woman turned out, on closer inspection, to be a boy. At the talk earlier that day, Michele had explained the piece in terms that could be applied to his designs. “It’s the idea that the most beautiful thing is the one that you really don’t understand,” he said.

The opening party culminated with the crowd moving to a music venue across the street for a performance by Leah Dou, an 18-year-old Chinese pop singer. Michele, nursing a glass of Champagne, made his way to the mezzanine, where Feinstein was seated in a leather chair, her foot propped up to reveal a cast. “I broke it just before coming here,” she said with a smile. “It was an incident involving opening a bottle of wine at my house on Long Island.” Though in good spirits, she was beginning to succumb to jet lag. “Basically, you have to keep drinking,” she said, raising her glass in the direction of Michele, who was leaning over the mezzanine to get an unobstructed view of the show.

He was captivated by the performance. Dou, a slight woman wearing a black Gucci ensemble, sang in a deep, throaty voice that belied her stature. “Oh, my God, I love her!” Michele exclaimed. In the morning, he would fly back to Rome, with trips to Milan and Los Angeles on the horizon, but for the moment he was in a decidedly contemporary state of mind: reveling in the here and now, finding connections between the exhibition and the performance. “Look at her!” he said, pointing to Dou. “So beautiful. She is just like the boy in my painting, do you see?”

Gucci’s Alessandro Michele: The New Romantic

A model in his installation, Gucci Tian, 2015. Model wears Gucci.

Alessandro Michele, photographed in October at “No Longer/ Not Yet,” at the Minsheng Art Museum, in Shanghai.

A model in the installation by the artist Unskilled Worker (Helen Downie), with portraits depicting looks from Gucci’s fall 2015 men’s and women’s collections. Model wears Gucci.

Gucci’s Alessandro Michele, flanked by (from left) the artists Li Shurui, Helen Downie, Rachel Feinstein, and Cao Fei.

A model in Li’s installation, with Mindfile Storage, Unit No. 1-5, 2015. Model wears Gucci.

A model in the artist Nigel Shafran’s installation. Model wears Gucci.

Gucci shirt, skirt, glasses, rings, bag, and shoes.