History, lovers of excess will be happy to note, has seen its share of Scaasi moments. And from the most opulent bar mitzvah in Great Neck to the long red carpets of Hollywood, those moments tend to have a few things in common: sequins and taffeta, feathers and fur, flashbulbs and applause.

There was Barbra Streisand, age 25, in her notorious see-through Scaasi bell-bottoms at the 1969 Academy Awards; Barbara Bush floating into the 1989 Inaugural Ball in sapphire-blue satin and velvet; Mica Ertegun in black ruffles the size of wagon wheels at a Paris party a few years ago; Carolyn Bessette, an unlikely Scaasi siren, in an orgy of sea-foam satin and taffeta at the Oscars.

“These are the moments,” Arnold Scaasi explains, “when I thought, There’s a very good reason I do what I do.” But that history of grand entrances—preserved in the designer’s 78 scrapbooks of press clippings—is only half the story. It’s the private moments between designer and pantie-clad client, when dressing often mingled with dishing, that form the backbone of Women I Have Dressed (And Undressed!) (Scribner), his new memoir.

Nowadays, Scaasi, 68, is famous for living as lavishly as the women he adorns. His tie is invariably cut from the same cloth as his bespoke shirt, and his Town Car (license plate: SCAASI) could probably drive itself from his remarkable art-filled apartment on Beekman Place to Le Cirque, where he has a regular table. Today, however, it is occupied by David Rockefeller. “Well, I suppose he has seniority,” the designer says.

Although Women I Have Dressed is organized by grande dame—Joan Sutherland, Elizabeth Taylor, Louise Nevelson, Rose Kennedy et al—and has some of the ambience of the French court before the heads started to roll, it also manages to tell the story of Arnold Isaacs, a “little Jewish kid from Montreal.” Happily for Scaasi, this is a rose-tinted look down memory lane. “I was the new couturier, though Mainbocher still existed,” he writes of his arrival on the scene in the early Sixties, having been introduced to fashion by his Vionnet-adorned Aunt Ida before stints in the Paris atelier of Paquin and then with Charles James in New York. “Scaasi,” he writes proudly, “was the designer you went to for fabulous clothes.”

His career has spanned generations: Before Scaasi dressed Nan Kempner, he dressed her mother, the San Francisco doyenne Irma Schlesinger. He was 23 when he was first invited to the Eisenhower White House, and he went on to dress three first ladies—Mamie Eisenhower, Barbara Bush and Laura Bush. (“Republicans,” he says, “seem to like my clothes better than Democrats.”) Then, of course, there was Hollywood. Scaasi happily spills several decades of its famous players’ most lurid secrets, including fake breasts, closet lesbianism and more. Claudette Colbert, he writes, confessed that she’d had an abortion because “her ambitious mother agreed when the studio heads felt a child would spoil her screen image as a ‘love goddess.’” Paulette Goddard once “ducked under the table” at the Mocambo nightclub to convince a studio head to give her a part; it worked. Joan Crawford, who cloaked her “football-player shoulders” with Adrian’s famous custom-made gowns, really did have a Mommie Dearest fanaticism when it came to cleanliness. The author recalls that the actress left her dirty underwear on a chair every night before bed, and the maid had to have it washed and pressed before Crawford woke up the next morning. “We always thought it was part of her guilt complex…it was widely rumored that she had made soft-core pornographic films in the beginning,” Scaasi writes.

About his first ladies, he is no more circumspect. Mamie Eisenhower had wonderful breasts, he reports, and never wore a bra. “I don’t want those terrible little wrinkly creases that most women have where the arm meets the body,” she once told him. “I prefer to look natural.” Socialites also get the treatment: The designer exposes Marylou Whitney’s habit of using vaginal ointment as face cream. “If it tightens everything down there, why shouldn’t it work up here?” she reportedly said.

On the subject of other designers, Scaasi is pleasingly wicked. He resuscitates the old story that Oleg Cassini copied French designs for Jackie Kennedy, and goes so far as to suggest that Cassini brought models to the White House for the benefit of the “horny young president” waiting upstairs. (Cassini, when W called him for a response, said, “That midget. The next time I see him, I’ll smack him.”) As for Michael Faircloth, who created an inaugural wardrobe for Laura Bush—she declined Scaasi’s services for the occasion—Scaasi maintains that the designer’s mid-calf coat made her look “dumpy.”

“The funny thing is that I hate gossip. But everything I reveal is true,” he says. “Somebody called and said, ‘You wrote that so-and-so did such and such, and that’s not a very nice thing to say.’ But I just wrote it. I didn’t think.” Scaasi insists that there’s not a single mean-spirited sentence in the book. “You can’t dress someone unless you have a rapport with them. And there are many women I wouldn’t dress.” He mentions Kim Novak, whose neck he once pronounced to be too short for high collars (she left Scaasi’s salon on the brink of tears) and Shirley MacLaine (“I like her, but we just think differently about dressing”).

It seems only fitting that the confidence of the designer should match the bravura of his creations. Indeed, Women I Have Dressed offers a little lexicon of decadent adornment: gray mink turbans, fishtail trains, candy-pink satin party cloaks, embroidered organdy evening pajamas. “My fantasy about women is like this”—Scaasi waves his arms in the air—“I want everybody to be bigger than life.”

Although the designer attained considerable financial success in the Sixties and Seventies, the Eighties were a particular heyday at the house of Scaasi. He describes it as “a wow of a time,” when his clients were the most glamorous women in New York: Blaine Trump, Ivana Trump, Anne Bass (“the best figure of them all”), Nina Griscom, Pat Kluge, Libet Johnson and Gayfryd Steinberg. “He’s a one-off, just like his dresses,” says Blaine Trump. “I’ll never forget the first Scaasi I wore—to the Met Costume Institute: a celadon gown with a big bustle in the back and a huge pink cabbage rose. This was simple by Scaasi standards.”

The designer has no interest in unsheathing his scissors for the latest group of socialites. “All the new girls are so dull and alike,” he says. “This is the Botox generation. They can’t smile more than a half smile.” Their style, he says, is no better. “Fashion is so ugly now, and what people are wearing! Women in jeans with unwashed hair, unkempt. I might have thought at one point, Here’s a gal who feels free. But what it really shows me is a lack of self-respect. I do like the Boardman girls, who you don’t sense are just out there to be photographed.” Hollywood fares no better in Scaasi’s estimation. “I don’t know who the f— they are,” he says of today’s starlets. “Although I’d like to dress Catherine Zeta-Jones. Gorgeous.

“I gather that today the actress stands in the middle of all the clothes and the stylist says, ‘No. No. Yes,’” Scaasi continues. “The stylist may have no taste at all, and then this actress comes out on the red carpet—so how can she feel? Barbra Streisand owned New York in 1969. You can’t do that in a dress you’ve seen for the first time two days before.”

But even Hollywood’s truly stylish starlets might find it hard to relate to the prescription for showbiz style in Women I Have Dressed: “Bright colors, beads and ostrich feathers,” he writes, “are the best ingredients for a standout look onstage.” Scaasi, who says that Galliano and Lacroix are among the few working designers he admires, clearly belongs to the old school. Today he confines his work to a small made-to-order business for “about eight very wealthy women”; he won’t name names, but they include Anne Ziff of the Ziff Davis publishing empire, and Christine Schwarzman, mistress of the palatial apartment at 740 Park Avenue that once belonged to Scaasi’s beloved Gayfryd Steinberg. Otherwise, the designer is happy to spend most of his time luxuriating over lunches at Le Cirque, weekends in Quogue and winters in Palm Beach with Parker Ladd, his partner of 40 years. He says that he has designed for almost every woman he ever wanted to.

“I would have loved to dress Cleopatra,” he adds. “If—” He pauses, then adds, “And only if—she was as glamorous as we think she was. And I would have liked to dress Madonna, but not today.” Scaasi leans back in his chair and scans the dining room. “The people you want to dress—if you wait long enough, they become very boring.”

Photos: Ladies’ Man

The book jacket.

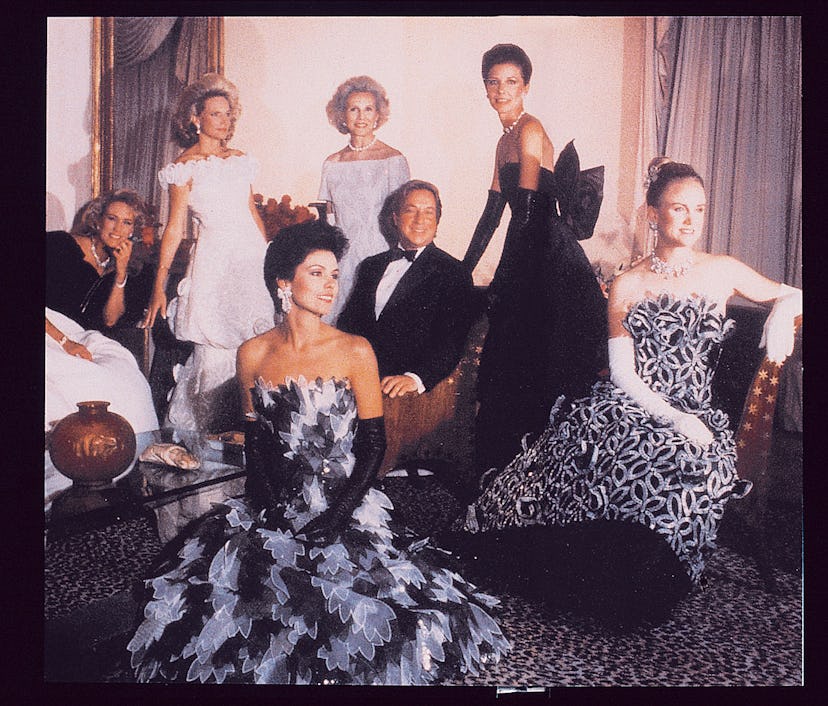

Scaasi with, from left, Patty Raynes, Charlotte Ford, Gayfryd Steinberg, Carroll Petrie, Kimberly Smith and Libet Johnson.

Scaasi with Barbra Streisand, 1969.

A feathered extravaganza from 1959.

Mary Tyler Moore in a “Me and My Scaasi” ad.

Scaasi with, from left, Barbara Bush, Laurie Firestone and Mimi Reed.

Elizabeth Taylor, 1986.

Aretha Franklin, 1990.