Domenico Gnoli Reborn

Is there any question more vexing for the devoted fan than what could have been? Admirers and collectors of the late Italian artist Domenico Gnoli must surely be asking themselves this question yet again this...

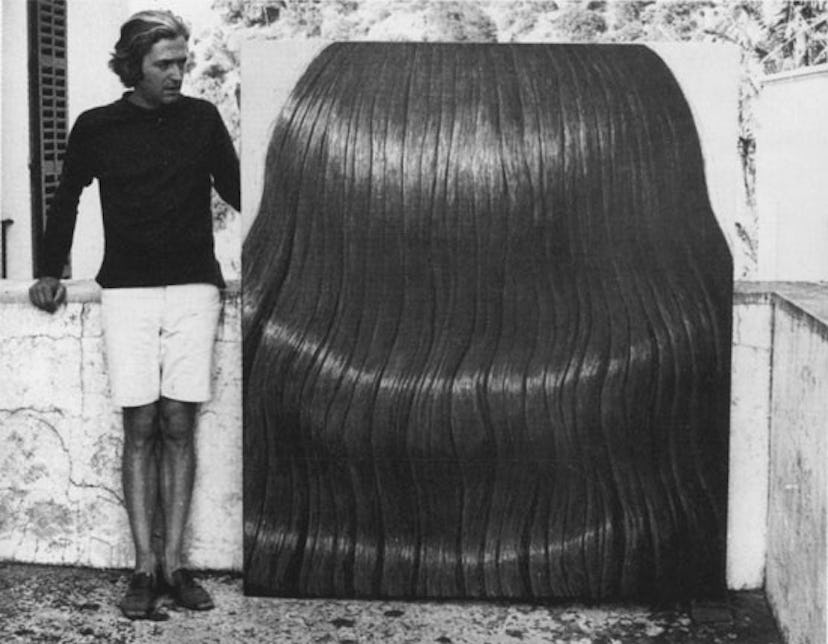

Is there any question more vexing for the devoted fan than what could have been? Admirers and collectors of the late Italian artist Domenico Gnoli must surely be asking themselves this question yet again this week now that New York’s Luxembourg & Dayan gallery has mounted the first U.S. show devoted to Gnoli since his death four decades ago. In 1969, after a successful solo show at the trail-blazing Sidney Janis gallery in New York, the beautiful, bohemian dandy with an abundance of talent—he was also a leading illustrator and stage designer early in his career—was poised to become a major art star. But his career was cut tragically short, when he died a few months later of cancer, at only 36.

Since then, Gnoli’s work has remained in obscure private collections (although a few pieces are also held in institutions like Rome’s Fondazione MAXXI and Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea), largely unseen by a public that has forgotten him. But now, prompted by the interest of prominent collectors (Miuccia Prada showed his work at the Prada Foundation’s Ca’ Corner della Regina palazzo in Venice during the 2011 Biennale), Luxembourg & Dayan is presenting 18 of his entrancing paintings along with his hallucinatory illustrations. The stylish canvases take secondary details—the collar of a man’s shirt, the wave in a woman’s hair—and blow them up into the primary subject with remarkable attention to pattern, texture and detail. (As the curator Francesco Bonami writes in the exhibition’s catalogue, “Who would be crazy enough to paint and enlarge a buttonhole today?”) The paintings magnify reality, until they become surreal. They will remind you to take a harder look at the present—a reasonable lesson from a man whose own present was foreshortened.

W recently caught up with gallerist Amalia Dayan to talk about about this lost and recently rediscovered talent.

Why do you think Gnoli’s work remained largely unheralded for so many years? I suppose it was because he didn’t make enough paintings. He died in 1970 when he was 36, and the mature, important works are from the last five years of his life. There are only about 140 of those paintings—not really enough to constitute a market.

So why is it attracting attention now? There’s been a general interest in Italian art recently. And a lot of this work has led people to look at Gnoli again, more closely. He’s so original and obscure, in a good way—the work has really captured the attention of some main players in the market. Also, the curatorial world—people like Bonita Oliva, Alison Gingeras, and Francesco Bonami—has been interested in his work for years. And even curators of a younger generation, like the Whitney’s Chrissy Iles, who came by to see the show yesterday, are fascinated by him. Somehow, it’s relevant! That is the feeling, anyway.

Have the prices for his work gone up recently? There is a huge demand, and very little supply. [laughs] So it creates quite a strong market. A few of the paintings in the show were for sale, which we sold before the show opened. We’re hoping to find more.

I’m curious about the artistic influences from his life. His father was a sort of independent curator, writer, and art historian. So Domenico really understood art history. He lists [Giorgio] Morandi as a major influence, which makes sense when you look at the work. In the beginning, Gnoli worked as an illustrator. He was an amazing draftsman, which I understand was almost a burden—how do you give that up? But he really wanted to be a painter, an artist. He met Yannick, his second wife and eventual widow, in 1963. She was the one who actually pushed him to make more figurative, less abstract paintings. And from 1964 onwards, he began producing these incredible canvases.

How was the work received during his lifetime? He was a golden boy, always successful. Even when he was an illustrator, it was always for the leading publications. He wasn’t a marginal figure. His show in New York, right before he died, was at Sidney Janis, one of the most important galleries at the time. So his work was accepted in a positive way—but it was strange work. It didn’t look like anything else at the time. It still doesn’t.

Gnoli’s focus on details of appearance—the braid of a woman’s hair, the pleats on a pair of men’s trousers—was so intense. Was he also very attentive to his personal style? He was stylish in a dandyish, bohemian way. He was very, very handsome—and apparently, a huge womanizer. He didn’t have a huge amount of money, but he drove eccentric sports cars and had a little sailboat. When he died at 36, he’d already been married twice—the first time to an Italian model for a few years, and then to Yannick. They ran in a tight circle of gorgeous friends. It was a glamorous group.

Did he have important patrons or influential friends who helped him? Yes, but they were not the obvious art world crowd—they were mostly poets, writers, editors, photographers.

Was he a part of the Arte Povera movement in Italy at the time? No, he was an outsider. He was a movement unto his own. And it’s not that he was unaware; he was highly informed about Arte Povera, American Pop art, Abstract Expressionism.

But he chose to go his own way. Which is the incredible, inspiring thing about Gnoli. It’s sad that he died at such a young age. I always wonder how his art would’ve looked had he lived.

Click here to see more of Domenico Gnoli’s artwork.

Photo: Red Dress: Alessandro Vasari