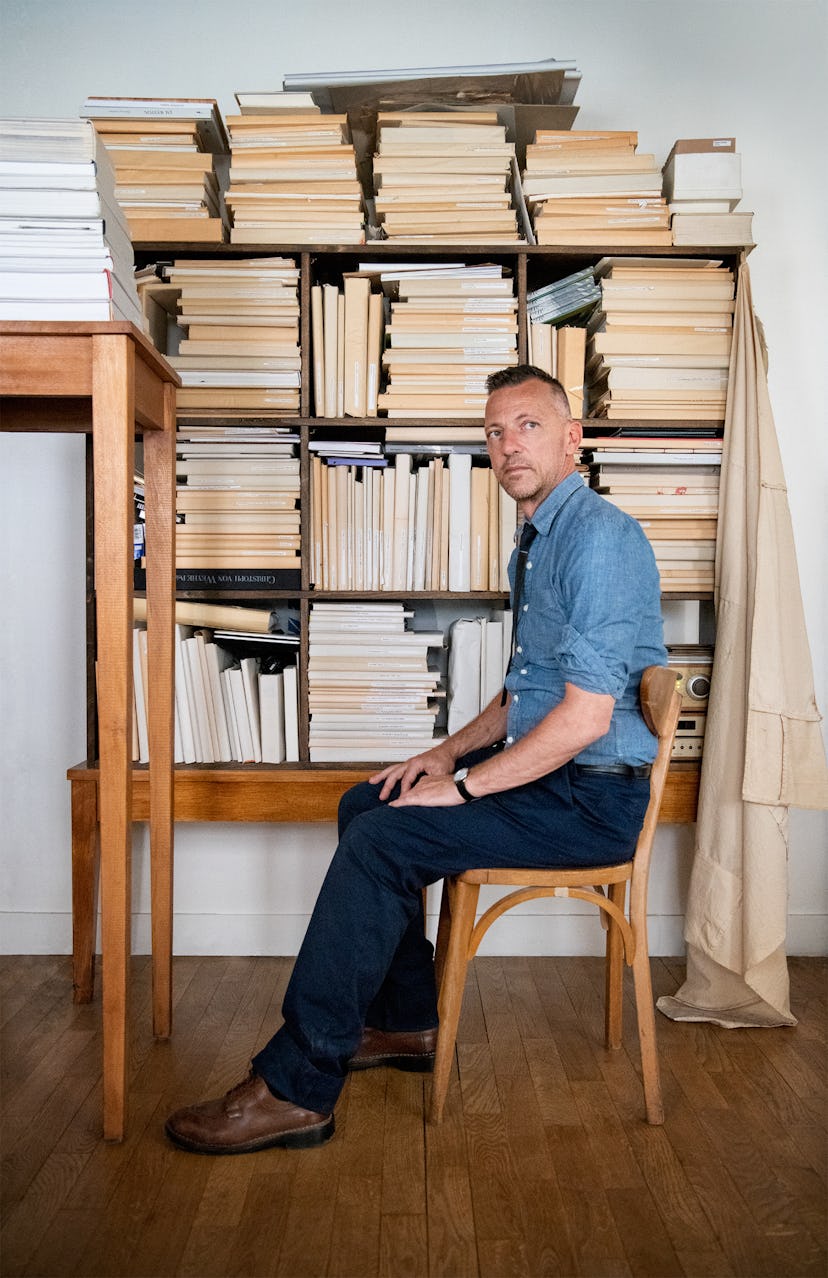

Meet the Man Behind France’s Most Famous Shoe Cobbler

Olivier Saillard, one of the world’s most prominent fashion curators, brings his artistic sensibility to the French cobbler J.M. Weston—and his own inventive side projects.

A little over a year ago, Olivier Saillard, known until then as a provocative museum curator of fashion, signed on as artistic director at J.M. Weston. Weston is a resolutely unprovocative French cobbler that has been around since 1891 and is known for, among other things, making the shiny black boots worn by France’s Republican Guard. On June 19, Saillard staged his first fashion show for the brand, with the intriguing title Défilé Pour 27 Chaussures. It was the damnedest défilé I ever saw.

Into a bare white room at Paris’s Grand Palais strode the celebrated modern dancer Mathilde Monnier, in black tights and a loose white shirt. For the next 30 or so minutes, this supple, dignified 59-year-old woman walked, slunk, crept, marched, and sauntered while she moved Weston’s iconic black shoes around the floor—mostly with her hands. It was wonderful dance theater, but will it help sell a single pair of Weston’s derbies? Wrong question.

“We’re talking here about the act of walking—human walking, military walking, funereal walking, runway walking, the walk of a woman alone onstage, and that—that’s just pure poetry,” Saillard says. “The day before the show, I was having lunch with Christopher Descours, the owner of Weston, and I said, ‘I want to warn you, it’s not really a défilé.’ And he said, ‘No, no—I get that you’re locating us on an artistic plane that others haven’t staked out.’ ”

Over time, Saillard has certainly proved he can do that. He spent most of his professional career at Paris’s Musée de la Mode. In 2010, he was named its director, presiding over its top-to-bottom renovation and reopening as the Musée Galliera, in 2013. From the beginning, Saillard did things his own way; his exhibitions were never about clothes on hangers. In “The Impossible Wardrobe,” for instance, the actress Tilda Swinton, a favorite Saillard collaborator, spent 40 minutes caressing garments from Galliera’s archive designed by such titans as Schiaparelli, Balmain, and Dior. In its offbeat, moving way, the performance managed to get deep inside how people inhabit their clothes, which is the space where Saillard lives. He’s not a surface guy.

This kind of thing got Saillard plenty of glowing attention, and some that was not so glowing. “It seemed to me, and I say this with all humility, that I was treating historical material more creatively. I could touch a different public. But sometimes the purists, the intellectuals, the conservators didn’t like that,” he says. By 2017, he was ready to split. He had already explored the work of the designers he cared most about—Lacroix, Alaïa, Gaultier, Yamamoto—and all that remained was continual fundraising. Still, he agonized before taking the Weston job.

A pair of [J.M. Weston shoes designed by Saillard for the Papers collection](https://www.jmweston.com/en/mocassin-180-collection-papiers-cuir-veau-box-noir-buvard).

“My mother said to me, ‘I don’t get it—you wanted to be a museum director and you got to direct one of the biggest, and now you want to run a boutique?’ ” he recalls, laughing. “That definitely did not help me make my decision. But recently, she said, ‘Now I see the connection!’ ”

Saillard is not entirely leaving his past behind—he was recently appointed artistic consultant for Pitti Immagine, the company that hosts the famous Pitti men’s-wear fair in Florence, and will curate fashion exhibitions for them. But the J.M. Weston Saillard promises to be, if anything, a looser, quirkier version of the museum Saillard. He’s already imagining something featuring the famous café waiters of Paris, who have long favored Westons for their sturdiness. He’s also building an entire storytelling edifice around the supposed character of J.M. Weston, who is an invented person. The name comes from the town of Weston, Massachusetts, where Eugène Blanchard, son of the company’s founder, went in 1904 to study Goodyear welt construction. In 1922, Blanchard decided to rename the company J.M. Weston, although it remains based in Limoges, France. To this day, no one knows where the initials “J.M.” come from.

“I love that!” Saillard says. “We can create a certain confusion that over time will get people to think that J.M. Weston really exists, that he’s both a poet and a hunter—his feet on the ground and his head in the clouds.” If you live in France, expect one day to hear radio commercials—fashion radio!—featuring readings of J.M. Weston’s poetry. (Saillard also happens to have spent some years in Japan, writing poems.)

Two t-shirts from his [Moda Povera collection](https://www.vogue.com/article/madame-gres-olivier-saillard-t-shirt).

That’s all delightful, you say, but what about the shoes? “The idea here is to do just a little bit better,” Saillard says. “We have no ambitions to open 50 stores in China. Nor are we going to turn to millennials—I always liked old people better than young people anyway. The shoes in the recent show all date from the 1930s, ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s. I’m going to start from there to build the future. Every time I invent a new shoe, I start with an old shoe.

”You can see what he’s talking about in Weston’s new limited edition line, called Papers. The shoes are classic Weston models—its 180 loafer, its tasseled derby lace-up—but printed with patterns taken from marbleized Florentine bookbinding paper, plain kraft paper, or, in one case, from an ink-spattered blotter that he found in the archives. Saillard adores rummaging in the lost and found of history with a small “h.” As source material goes, it’s old and it’s ordinary, and yet it comes off as surprisingly fresh.

I beheld just how unexpected Saillard’s forays into fashion’s past—and possible future—could look about a week after the Weston défilé. He was showing a line of T-shirts he had created for Moda Povera, a side project of his that takes its name from Italy’s bare-bones arte povera movement. Saillard started with the cheapest oversize T-shirts he could find online, joking that they cost him more to ship than they did to purchase. The idea was to show how, in a world that often worships luxury for its own sake, the simplest, cheapest materials, in the right hands, can soar.

The living room of Saillard’s apartment.

And it just so happened that Saillard had the perfect pair of hands for the job: those of 75-year-old Martine Lenoir, who had worked in the dressmaking atelier of Madame Grès before her death, in 1993. Saillard has long admired Madame Grès—in 2011, he staged an exhibition of her signature delicate drapery at Paris’s Musée Bourdelle. For this project, he asked Lenoir to cinch and pleat the humble T-shirts until they resembled Grès’s pieces. To display the 27 looks, Saillard enlisted Axelle Doué, a 62-year-old model who had also worked with the legendary designer.

The results were extraordinary. Doué looked like she had just stepped off a pedestal at the Acropolis, her silver hair pulled back in a bun, a half-smile on her face. The white, green, orange, and red T-shirts had no embroidery or embellishment other than the pleats and darts Lenoir used to transform them into updated Greek chitons. Were they formal? Were they informal? Impossible to say. You could imagine pairing them with blue jeans or wearing them to a formal dinner. You can talk all you want about the elevation of streetwear to high art, Saillard seemed to be saying. Well, this is streetwear, too, but for an eternal street where fashion—fashion in a much deeper sense—never dies.