Enforced Disappearance

In his first new work since being released from government custody, Chinese art star Ai Weiwei collaborates with W on a series of arresting images—from half a world away.

One evening this past August, a group of corrections officers were milling about the James A. Thomas Center, some near a metal bin that read: load and unload all firearms here. Inside cell block number two, a shower was running. It could have been any summer night on Rikers Island, home to New York City’s most notorious jail, were it not for the presence of the Chinese model in the shower, the photographer shooting her, the assorted assistants monitoring screens, and the dissident Chinese artist Ai Weiwei.

Though Ai was not at Rikers in person, he was following the action closely via Skype and orchestrating the scene from his studio 13 time zones away, in Beijing. Detained by Chinese authorities in April, he had disappeared, spending 81 days in a Beijing jail and prompting an international firestorm of protest. Released in June, Ai, China’s most famous and influential contemporary artist, has been prohibited from speaking publicly, giving interviews, or leaving the city—and must get permission even to travel outside his studio and home, where he lives with his wife. But he accepted W’s invitation to create a commissioned work for its sixth annual art issue. In preparation for the project, Ai outlined five scenes that explore what he called “the conflicts between individuals and authorities—be they economic, cultural, political, or religious. I am using my personal experience to address a condition.” Having e-mailed us his concept for a series of film stills, we were tasked with executing his ideas.

“Hello!” he said brightly as his friendly round face, framed by a wispy beard, floated on the screen of the laptop we’d positioned near the shower. “Where are we, exactly?” Rikers Island, I told him. Ai surveyed the shower room, the model, and the two figures flanking her. Emanating from the screen were the sounds of his studio menagerie: some 20 vocal cats, three loudly chirping birds, and various barking dogs. Spying the rusty grout lines between the gray tiles, he advised photographer Max Vadukul that they should appear less pronounced. “Otherwise, it looks good. It has a snap-photo quality,” he said, holding his iPhone up to his computer to take his own picture of the scene.

Vadukul made the necessary adjustments and showed Ai the photos he had just taken on a nearby monitor. He then e-mailed images for the artist to review. As they were downloading in Beijing, we took Ai on an improvised tour of the jailhouse, carting the laptop around the cell blocks, much to the bemusement of the officers on duty. We pointed out that we were in the island’s original Deco building, constructed in 1933 and now used for training and occasional film and TV shoots.

Ai knew of Rikers, having lived in New York’s East Village from 1982 to 1993. He briefly took courses at the Parsons School of Design and the Art Students League and worked odd jobs as a sidewalk portraitist, an extra at the Metropolitan Opera, and a babysitter. (He was also an avid blackjack player, taking frequent trips to Atlantic City by bus.) Though he had studied film at the Beijing Film Academy, he made some of his first forays into photography with the snapshots he took daily in New York, which sparked his realization of the role art could play in political and social action. In fact, the documentary-style pictures he took of the 1988 riots in Tompkins Square Park—as well as other scenes of arrest he’s witnessed—served as a touchstone for the series he created for W.

“I took confrontational photos of undercover police taking people away, and the moment was very dramatic,” he recalled of the riots when I reached him by Skype a few nights before the Rikers shoot. “People would ask, ‘What is going on? What is behind the charge?’ and ‘What is the result?’ It is a moment that raises a lot of questions.” That early experience, he said, “gave me an opportunity to become aware of a brutal condition: that authorities abuse their powers. If we see life as a one-hour-long film, my experience in New York was the first half hour. It shapes what happens later.”

The personal has long been the political in both his life and work. The son of Ai Qing, one of modern China’s most renowned poets, Weiwei grew up in the hinterlands, in a forced exile with his family that lasted until the end of the Cultural Revolution. By 2008 Weiwei had become one of China’s cultural ambassadors, known around the world for his collaboration with Herzog & de Meuron on Beijing’s Bird’s Nest stadium for the 2008 Olympics. In his diverse roles as artist, urbanist, designer, and architect, Ai often calls attention to issues sparked by the collision of traditional values and the unbridled rush toward the new. In a seminal photo series created in 1995, for instance, he smashed an irreplaceable Han-dynasty urn to pieces; in another work, he emblazoned an ancient urn with a Coke logo.

Increasingly for Ai, technology and social media have become as much a medium as a tool, a kind of performance art in which we are all participants. He has more than 100,000 followers on Twitter—and that number is growing, despite his recent silence. “I think restrictions are an essential condition in the fight for freedom of expression,” he told me in an e-mail. “It’s also a source for any sort of creativity. Technology liberates us as individuals. It makes me happy to think that it has become a part of me.”

In the wake of the 2008 earthquake in Sichuan province that killed thousands of children (reportedly, their schools were built using substandard materials because of local corruption), Ai used his blog to mobilize activists to collect the names of the dead after the government refused to supply them. The resulting installation, Remembering, covered the facade of Munich’s Haus der Kunst with close to 9,000 children’s backpacks that spelled out she lived happily in this world for seven years—a quote from a mother of one of the children. When I asked him what role he plays as an artist in helping others understand change, he replied, “I spend most of my effort liberating myself from being an artist to becoming a real human being.”

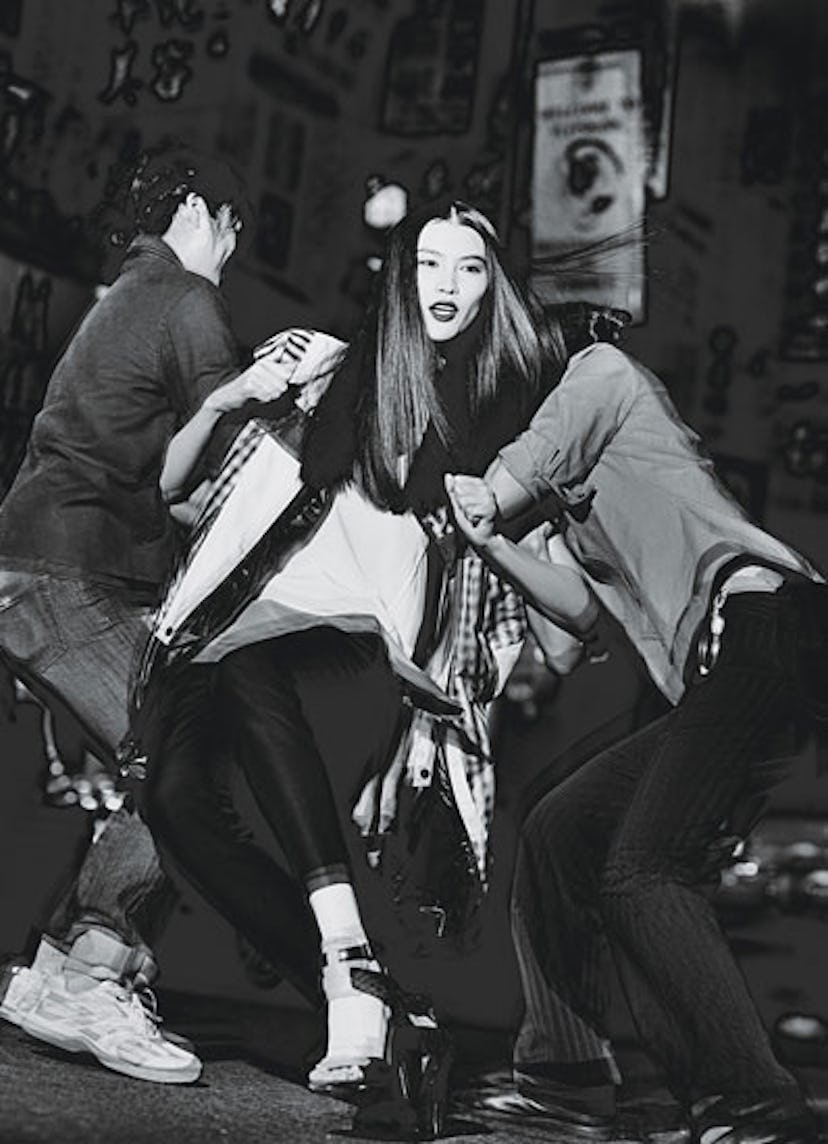

It was nearing midnight in New York when we called Ai to tell him we had shifted locations and were now on the street. “Are we in the Bowery?” he asked, scanning the riot of storefronts and signs through our laptop. “We’re in Chinatown, in Flushing, Queens,” I told him. As onlookers gathered, drawn by Vadukul’s flashing camera and a model dressed head to toe in Alexander Wang, we hastily wrapped the laptop in a hood to keep Ai from being recognized. Vadukul took some test shots of the scene, which, according to Ai, could depict “an anonymous person in London, Beijing, an Arab nation, or elsewhere in the world” being arrested and detained by authorities. “The individual can be charged, or not charged—with no clear explanation.”

On his laptop, Vadukul opened the images he’d just shot, then walked over and positioned it, screen to screen, with the one that showed Ai sitting at his desk in his Beijing studio. In this way Ai could see—despite the fact that it was now dark—and give instant feedback. Soon we sent him a file and then watched Ai scroll through the shots we’d just taken—images with, presumably, a powerful resonance. He told us which pictures he liked, and we went back to work. “It was helpful to have his voice in my head,” Vadukul recalled the day after the shoot. “The flow of his innermost experiences began to transfer to my photography; it was all moving very fast.”

Artists have long collaborated with assistants, and Ai often realizes his projects with a team of specialists that works in a factorylike manner. “I am putting less effort into personally producing the work,” he recently told Chris Dercon, who oversaw Ai’s Haus der Kunst show and is now the director of Tate Modern. “Others executing the work always means there is a kind of surprise, as well as a form of collective wisdom.” Still, it would be safe to say that no artist has ever worked as closely with his team from such great a distance as Ai did in the making of this project. “The feeling and emotions were close, but the camera was so far away,” he later told me. “The process became a part of the work. Art is always about overcoming obstacles between the inner condition and the skill for expression.”

It was nearly 5 a.m. in New York when we wrapped up. The surreal mash-up of art, technology, fashion, culture, and, not least, Ai’s presence, had kept the entire crew exhilarated throughout the night. I called Ai to tell him we were done. “That was a unique experience, no?” he said with a laugh. Two weeks later he was still digesting and savoring it. “I think this would have made both Leonardo da Vinci and Andy Warhol jealous,” he told me. “I laugh when I think about that. It reminds me of a poem that my father wrote before the Berlin Wall collapsed. He said, ‘It doesn’t matter how tall, how long, how thick this wall is, it can never stop the wind, the air, and people’s desire for freedom.’ Our desire for freedom is stronger than the wind.”

Chinese artist Ai Weiwei collaborates with W magazine

Model Sui He by Ai Wei Wei for W‘s November 2011 cover.

Styled by Wendy Schecter. Hair by Shay Ashual for Redken at Tim Howard Management; makeup by Maki Ryoke for Nars Cosmetics; manicure by Alicia Torello at the Wall Group. Model: Sui He at New York Model Management; extras: Shing Ka, George Ding, Kathleen Changho, Kiai Kim; casting by Laine Rosenberg. Produced by Sabine Mañas for Ghibli Media Productions Inc.; production design by Anne Koch; digital technician: Don Broadie. Photography assistants: Matt Roady and Nicholas Ong. Fashion assistant: Rex Nyas. Fashion: Alexander Wang’s polyester vest, silk tank tops, and ramie and viscose trousers. Alexander Wang shoes. Beauty: MAC Mineralize Satinfinish SPF 15 Foundation in NC20; Cream Colour Base in Pearl; Powerpoint Eye Pencil in Engraved; Eye Brows pencil in Velvetone; Zoom Lash mascara in Zoomblack; Sheen Supreme Lipstick in New Temptation.