Petra Collins and Betty Tompkins: An Intimate Conversation About Women and Art

The rising star and the feminist icon swap Instagram tips, take Donald Trump as their muse, and discover that some things never ever change.

One afternoon last week, Petra Collins beat me to the downtown New York home of one of feminist art’s grande dames, Betty Tompkins. When I arrived at the SoHo walk-up that doubles as a painting studio—Betty took it over 40 years ago, when it surely went for nothing—I could tell that Petra was excited. I’ve seen her on Levi’s campaigns, all over Instagram, and out around town. Her shock of hair, like Betty’s, is hard to miss. But I’ve never seen the 23-year old photographer and artist look so jittery, and I don’t think it was because of the uprightly-propped, high-stacked, and easeled canvases depicting vaginas, penetration, and oral sex that seemed to have taken over the place. After all, that kind of thing is right in Petra’ provocation zone.

Her anxiety can best be articulated by the print-out of questions and talking points—on ruled notebook paper, because in her rush she had forgotten to check the printer—she had brought for what I imagined as a casual chat with Betty about sexually empowered art and women in the art world, subjects that already fuel their lives and work and thoughts. Betty, 70, is enjoying what might be described as an autumnal renaissance, except I don’t think she was ever this hot in the art world until now. Her latest solo show, at the Flag Art Foundation in New York, is a stunning blow: 1,000 small paintings of words used to describe women. Betty didn’t betray any sign of her late-breaking celebrity, however. She ambled over, handed us each a glass of water, and leaned back in her chair.

Petra Collins: Betty, I wrote this down in my notes. I want to ask you about what your college teacher said to you.

Betty Tompkins: When I was an undergraduate, one of my teachers asked me, “What are you going to do after grad school?” I said, “I’m going to New York, and I’m going to become an artist.” And he replied, “The only way you’re going to make it in New York is flat on your back.” When someone says this to you at 20 years old, it has a way of sticking in your brain. So when I came to New York, and I had my first appointment at a gallery all the way up in a very fancy Upper East Side building, all I heard was that man’s voice in my head. I was sexually terrified! He basically told me I had to cooperate in rape. So when I got off the elevator, I went to the ladies [room] and threw up. I gave myself a talking-to: “If you really want to be a part of this art world, then you have to figure out a way to deal with it one way or another.” So I cleaned myself up, and I went in and introduced myself. He was an older gentleman, and he was not at all interested in girls. I figured this out upon hello and calmed down—and we had a wonderful time! And after that, it wasn’t an issue. I ran into it once or twice with collectors, but never with dealers. If a collector invited me over to his place, I made sure to bring my first husband with me. “Hi, we’re here!” And it worked. As the years pass, every once in a while I would think of what that teacher said. It was so mean-spirited of him, a hateful thing to say.

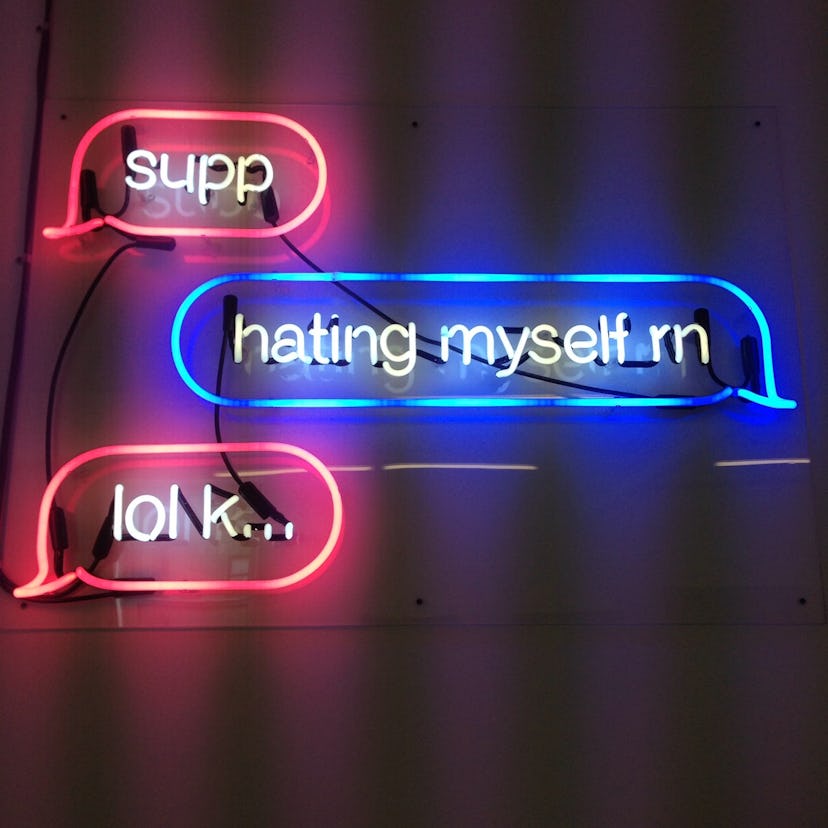

Collins: I’ve had a couple similar experiences similar. But it’s more like it’s weird and difficult to be a young woman to be taken seriously for what I do. All my work and my photography focuses on young girls. I also make these neon works from actual text messages. [She shows Tompkins examples on her phone.]

From Petra Collins' Neon Works series.

Tompkins: This is great! These are funny. Are these actual text messages you’ve gotten?

Collins: And ones I’ve sent. This one says: “Wish U Weren’t Here.” That’s a text from me. And this is from a series featuring Rihanna lyrics: “Baby/if I don’t feel it/ I ain’t faking no no.” I feel like Rihanna’s one of the most progressive female pop stars because her lyrics are so sexually empowering. With her, there’s this message that you own your sexuality, and that you can choose to be dominant or submissive. So anyway, there are two examples from when I went to go meet gallerists. One I met in L.A., and he just looked through my work uninterestedly and told me that I had to take 10 years to grow up.

Tompkins: You mean that line hasn’t changed since my day? Please. You’re supposed to be the empowered generation, for crissakes.

Collins: I know, it’s crazy! When he said that to me, I’d already been working for six years. I’m 23 now, but I’ve been working since I was 15.

Tompkins: There’s default misogyny, and there’s misogyny that is built into girls. What really set me off on this subject is this show that I am in at the Dallas Contemporary called Black Sheep Feminism. Alison Gingeras is the curator and also a writer, and she said that the genesis for the show came from when she looked at the artists she was writing about, and they were overwhelmingly male. And of course, that reflects her opportunities in the art world. She’s the world’s expert on Jeff Koons, for instance. But she said that she started to examine her own misogyny, its roots, and what should she do about it. Then I realized that some of the worst phrases and words that appear in my work came from women. Yesterday, there was a thread that tagged me on Facebook: it was bubble chart of how Donald Trump and his supporters describe women.

Collins: Yes! I’m really excited to talk about this.

Tompkins: He had plenty of “bimbo” and “bitch,” but proportionately he was short on “slut” and “cunt.” There’s so much material out there that I think I’m going to do my “women words” series for the rest of my life. I’m never running out, I’m never repeating. What a gift Donald Trump and these people are giving me!

Collins: What I found so funny about what you just said about Donald Trump, but also so much of what is the Republican-speak about women, is that we are either a bitch, cunt, slut—or mother. It’s interesting. To go back to how we were treated at the galleries, I was reading this one interview with you written by a man. He wrote: “How can I not be conflicted surrounded by massively scaled representations of explicit sex in the presence of a woman almost exactly my mother’s age?” It’s funny that as a woman creating work like yours, and as a younger woman creating similar work, we’re both treated with a different sort of disrespect and dismissal. As an older woman, you’re not supposed to be sexualized. That one thing rang true to me—that at my age, I’m seen as too young or sexualized, and I’m not allowed to show work because of that.

Betty Tompkins …She Also Paints, 2015

.Courtesy of the artist and GAVLAK Los Angeles/Palm Beach[/caption]

Tompkins: Before they passed laws in New York State about asking such questions, dealers would come to my studio and say, “What are your plans to have a family?” I had a good time watching them squirm. The unfunny part of course was that they were unwilling to consider investing even one minute or dime into an artist who was going to go off and be a mother. Probably for good reason.

Collins: I grew up in the early ’00s when music videos and media were at the height of overt sexuality. It was Paris Hilton and all that. From the beginning of puberty, I did really badly in school. I was super dyslexic, I was in special ed. I had a hard time reading and writing, so I thought that my self worth was in my looks, how I presented myself, and how other people perceived me.

Tompkins: I think it’s essential for both sexes, to know they look wonderful. But why didn’t I? A lot of therapy would help me answer that question. But I think I’m beautiful now, so screw it. Save the money.

Collins: I remember being 12 or 13 and reading Seventeen and CosmoGIRL. They were all about self-improvement. I didn’t even have a period or boobs or pimples, but I was still like, “I have to buy this product because it’ll make me beautiful.” That’s what I grew up on. It’s such a hard thing to shake. There’s that internal misogyny that I have.

Tompkins: You were trying to please.

Collins: Yeah. It’s difficult to figure out what my sexuality is, what I want to be instead of what I thought I had to do. And now I’m 23 and know how things work, but in the back of my head I still feel that.

Tompkins: Lately, I’ve been thinking about who I looked up to and who helped me when I was your age. I did an interview with Marilyn Minter in the fall. She asked me that question: “You must have had people behind you, who were they?” Aside from my high school art teacher, I had a hard time thinking of anybody. When I came to New York, I didn’t live downtown where all the artists lived. The only person I knew was Chuck Close. So I would go around to galleries, and every once in a while people would speak to me. It didn’t even occur to me that I was isolated. I didn’t say myself, “You’re in the middle of the art world,” because I didn’t know anybody! [laughs] When Marilyn asked me that question, I went, “Oh right. I was supposed to have a crowd.” At the time, there was so little available for women in the art world that it made women cutthroat competitive with each other.

Collins: Because there’s only supposed to be one spot.

Tompkins: Right. What I really like about the younger people who I work with now is that your generation really knows how to lean in and be supportive. You’re raised with a much different idea of teamwork than my generation was raised with.

Collins: I think it’s also about the accessibility that the Internet and communications has brought into our lives.

Tompkins: Absolutely. Also, there’s this idea of, “They don’t want me? I’ll create the opportunity myself!” Which is something I’ve said for decades.

Collins: Why wait? I did two years at art school in criticism and curatorial practice, but I dropped out because I was frustrated that there was this hierarchy where I couldn’t do anything or ask questions. When I was 16, I created this online platform for female artists. I messaged women who I loved; that’s how I got work and connected with people. You don’t need to plead for entry into a system that doesn’t want you anyway.

Tompkins: Exactly. Which is how I started with the “F–k” paintings. It started with the idea that galleries telling me they don’t show women was supposed to be crushing for me. But in fact, it was so freeing. Nobody gave a shit! So I thought, “Cool. I can do what I want. Now what do I want to do?” I was going to see all the shows, because the art world in New York was so tiny back then. Picture 57th Street from Park Avenue to Sixth Avenue. That was basically all there was of it. And I was going in and out of these galleries, bored out of my mind. So one day, I was looking at my first husband’s porn collection. He had these porno photos, and I just started to crop them and change the angles. I had been trained in abstract expressionism and grew into the Pop era. I said to myself, “Abstractly what you’re looking for is sitting right here, in two by three inches, right in front of you. This is as good as anything you can invent.” Plus, there’s this subject matter that has a charge. If I went into a gallery, I would want to look at this. I would stand there for as long as it took for this painting to tell me its story. That was a huge moment for me. I started “F–k” painting number one the next day.

The point, I guess, is I wasn’t painting for anybody. I think you’ve also come to this through rejection. You either cave to the rejection and you start looking for something that will please whoever is rejecting you, or you stand your ground and do it for yourself.

Collins: Yeah, I feel like right now the art world I experience is a lot of artists who create work to be sold. They’re always so boring, so uninteresting. And I don’t want to say that it’s hurtful, but I like you always created work because you needed to.

Tompkins: I have dealers, and I understand their concerns, but I don’t make work for them. I was in this group show at Marianne Boesky’s gallery a couple years ago called “Sunsets and Pussy.” She asked me for two major cunt pieces. I do them all the time, and I had a lot of time, so it seemed fine. I was in my studio in Pennsylvania, and the first painting basically fell off the airbrush without a hitch. But the one I started here in New York was a struggle. I couldn’t figure out why. Marianne and her assistant would come over periodically to check on my progress. When she came a week before the truck was coming to pick it up, I said to her, “This painting is not working. I’ll solve it one day, but I may not solve it in the next seven. And if I don’t, you’re not getting it.” The painting continued to be crap, and I’m getting emails from the gallery: “How’s it coming?” “Still shit.” Finally, the last day—the truck was coming first thing in the morning—they gave me until six o’clock to tell them yes or no. At five o’clock, I looked at the painting and said, “You have nothing to lose here.” I made radical changes. I had not liked this one area that had pubic hair stubble on it. So I took it out! Altogether. And it became so faint, just this faint interesting area. I said, “Now we’re a little off.” So I added a shadow. And in 45 minutes, I had changed the entire dynamic of the painting. And it remains one of the best paintings I have ever done. It is so off-balance, so off-kilter, it is holding on by its teeth. And at the same time, it’s sitting there in its rectangle saying, “Look at me. I’m great.” The next morning, I put it on the truck.

Betty Tompkins Cunt Painting #20, 2013

Courtesy of the artist and GAVLAK Los Angeles/Palm Beach[/caption]

So that’s an example of how not to do it. [Petra laughs] If I think, “I have to solve this problem because I really want to be in this show,” then I’m doing what I think of as “stinking thinking.” You have to be really honest with yourself at all times. And I really want my collectors to like what they have, because I don’t them to turn around and flip it.

Collins: It’s funny because I have such a weird relationship to the art world. I hate to constantly say it’s a boys club, but there are all these young male artists who are creating works constantly for collectors. It’s very disheartening. There are all these jock artists, these bro artists.

Tompkins: There have always been jock artists. It’s a jock artist world! It’s the safe thing to do; it separates your art from that pressure. Artists your age don’t have the life experience to say no to the buck. I hope that doesn’t sound condescending.

Collins: Not at all. But I was just so shocked. I guess I was very naïve when I saw everything in a context I had not expected. The second part of that was to create these spaces outside of that institution. And that’s getting better and better. There are so many great alternative spaces for young artists to show their work.

From Petra Collins' Selfie series.

Tompkins: I’ve been on social media for probably 10 years. And it started with some of my students at the New School. They said, “Betty, you have to join Facebook.” And the art advisor Ingrid Dinter found me on there, and that started this recent renaissance of mine. And this Flag Art show is because of Facebook. I friended Glen Fuhrman, the founder of Flag. This was four years ago. And he came over to my studio, and then a few years passed and I asked if he wanted to come back. And he saw this pile of small canvases stacked in the corner—it turned out to be 1,000 canvases. I realized that I had a choice: what I said to Glen and Stephanie, his director, was that I want to show all of them at once as one piece. That’s how I think of them. To my immense amazement, they agreed! And now it’s up, and it’s awesome.

Collins: What social do you have?

Tompkins: Facebook was the first. And then Marilyn Minter told me how to do Twitter because it had interesting articles. I downloaded Twitter, and somehow Instagram ended up on my phone, too. And I had always said I can’t do Instagram because I’ll get booted off in two seconds. Look at what I do! One piece of my work and I’m finished. But I thought, “Well it’s already here on my phone.”

Collins: Do you still use it?

Tompkins: Yes, I’m very active. I’ve been flagged several times, and things have come down. And even before I went on it, my dealer Rodolphe Janssen said, “Betty, you may not know this but your images are all over Instagram.” I did a search, and it was hundreds and hundreds of photos of my work. I’m told I do well but frankly I’m just making it all up as I go.

From Petra Collins' Selfie series.

Collins: [thumbing her phone] I just added you. Because I post photos of girls, I get a lot of comments. Instagram has been something that has been central to my career. There have been two things that happened: One, I created this T-shirt with American Apparel, it’s a very simple line drawing of a woman masturbating and menstruating at the same time. I didn’t think anything of it, but it ended up being this really controversial thing on Instagram. And the other time is when I posted this photo of myself in my underwear. There was a tiny bit of pubic hair visible. I was flooded with hundreds and hundreds of comments like, “This is disgusting, why are you showing this image.” And then my account was deleted. And I started to look into the same type of photo—bikini photos, basically—but the one thing that was different from mine was that there was no pubic hair.

Tompkins: The world has a lot of trouble with this kind of thing. But I’ve always felt that negative reactions to my work have always had more to do with the person voicing the opinion that it ever had to do with my work. To me, that’s part of the business end. I don’t have any problem not being hurt by it.

Photos: Petra Collins and Betty Tompkins: An Intimate Conversation About Women and Art

From Petra Collins’ Selfie series.

From Petra Collins’ Neon Works series.

From Petra Collins’ Selfie series.

From Petra Collins’ Selfie series.

This interview has been edited and condensed.