Celine Brings the Work of French Sculptor César Back to Life

Inspired by 1970s Paris, Celine artistic director Hedi Slimane reimagined César's jewelry compressions for a new generation.

If you happened to be walking down a street in Saint-Germain-des-Prés circa 1971, chances are you may have encountered an elegant Parisian woman or two with a mottled, golden rectangle the size of a piece of boxed chocolate hanging on a chain around her neck. Look closer at the pendants and you might have seen a warped length of ring, a medallion shaped like a pancake cooked on a too-hot pan, piles of chains and diamond studs fused together like fossils in petrified earth.

These little totems were art pieces made by the French sculptor César, a founding member of the Nouveaux Réalistes group, who sought to honor the integrity of the everyday materials with which they worked.

Best known for the massive, compressed sculptures he made using scrapped car parts and hydraulic presses, César also worked for a time on a smaller, much more personal scale. In the early ’70s, he began to ask friends and acquaintances to bring him the piles of unworn but sentimental jewelry—not-quite-right gifts, childhood charms, stones in dated settings—gathering dust in drawers. Then, working with a goldsmith, he would transform the lot into a single piece of modern, wearable sculpture.

Stéphanie Busuttil-Janssen, the founder and president of the Fondation César and the artist’s companion and muse until he passed in 1998, describes the jewelry compressions as “memory sticks,” that retain the emotional resonance of the source. “He liked to re-use scraps of old things, recycling and giving things a certain sense of rebirth and life,” she said, speaking on the phone from her home in Brussels earlier this month. “The idea is really about transforming something with a soul.”

The compressions were never shown in galleries, but rather commissioned by word of mouth in the sorts of circles chronicled by Slim Aarons and his camera. Brooke Shields had one made, so did the heir and international playboy Gunter Sachs (although Busuttil-Janssen didn’t say for whom). “It was always beautiful women who had one,” Busuttil-Janssen said with a laugh. “It was all very sexy, intellectual, jet set.” In 1973, Hachette published a book, complete with a textural gold cover, about the compressions, with essays by Françoise Giroud and James Baldwin, who was César’s neighbor in Saint-Paul-de-Vence.

Left: César, Compression en or et diamant, Circa 1970, 4,8 x 1,8 x 1,8 cm. Courtesy Sorry We’re Closed Gallery / Brussels. Right: one of the new editions in vermeil released in collaboration with Celine.

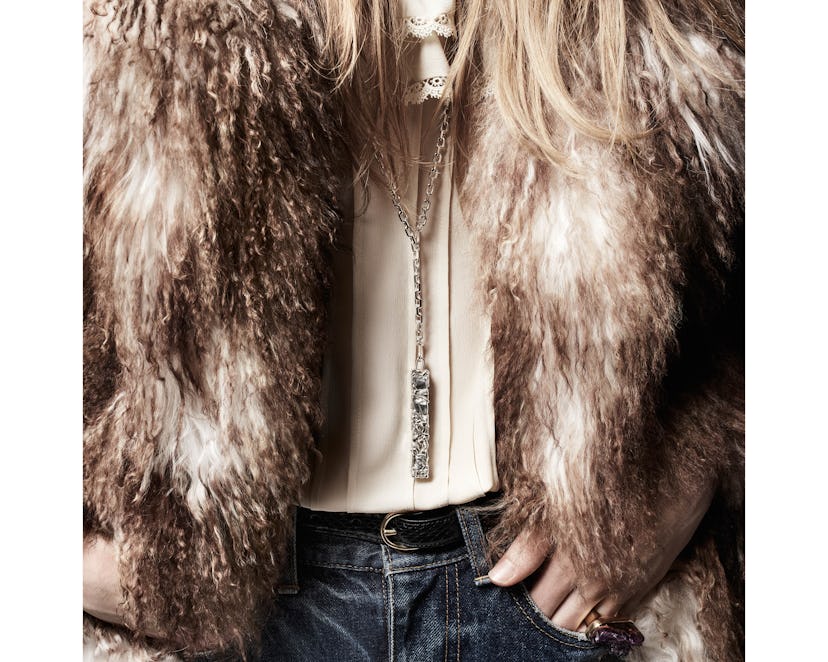

Today, on the streets of New York, Seoul, London or Cape Town, you may start seeing them again, albeit in a slightly different form and worn by a new generation. Celine, in collaboration with Busuttil-Jansen and the Fondation César, has just released a limited edition of compression pendants inspired by the artist’s legacy. Made in an edition of 200—100 in gold vermeil, another 100 in silver—each piece has a retractable hook that allows for it to stand on its own as a tiny sculpture.

The tactile pieces are meant to be held, which is why they’re mounted on a long chain that allows for easy reach—imagine fiddling with one while on a long phone call or waiting for someone at a bar.

For Busuttil-Jansen, the collaboration felt like an exceptionally natural one, both in terms of the spirit of artistic director Hedi Slimane’s work and the conversations between the foundation and his studio: “It was like ping pong, super easy to work together,” she said. And the “60s-70s French bourgeois de l’amour” vibe of Slimane’s clothes made for a coherent match.

“As an artist, Hedi really wanted to respect what César had done when he was alive,” Busuttil-Jansen said. “So we even did an adaptation of the box that he used in the 70s, a very humble pine box. He really loved the opposition with gold and pine wood, that poor and rich opposition that Hedi loves, too.”

Perhaps most importantly, Busuttil-Jansen thinks César would have loved the idea of introducing his work to a new audience, specifically a younger, fashion-forward one who might not be able to spring for an original at auction. “He would be very happy with it. He was very connected with architecture, with fashion,” she said. And as the head of the foundation, her mission is to show the contemporaneity of his work. She’s happy with the results, too: “It’s chic, it’s sexy, it’s classical and a bit decadent at the same time.”

Related: Celine’s Spring 2020 Show Begs the Question: Is This the New Hedi Slimane?