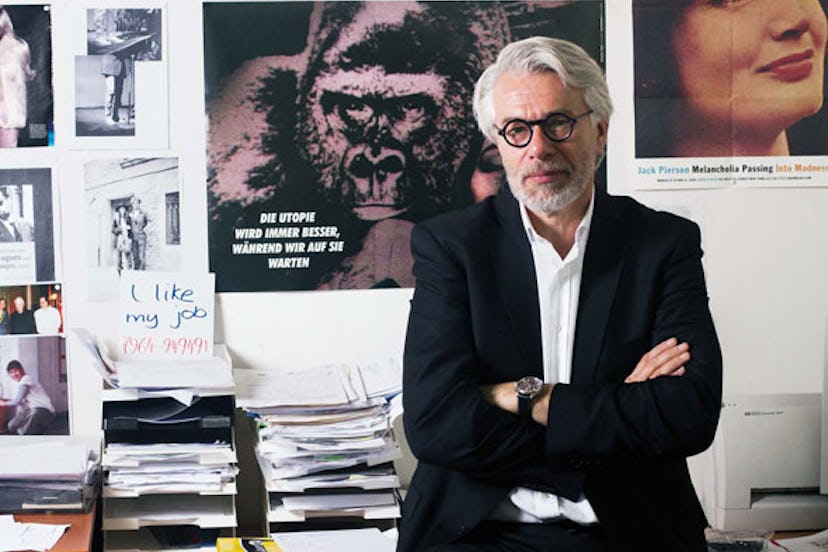

Modern Master: Chris Dercon

With his appointment as Director of London’s Tate Modern, Chris Dercon joins the establishment he once challenged. Alice Rawsthorn meets the art world’s newest power player.

WHEREVER HE WORKS, Chris Dercon pins a cluster of photographs, sketches, and notes on his office wall. “I call it my collage,” he explained. “It’s very, very important to me—a collection of the things I like to look at every day.” At his last gig—as director of Haus der Kunst (literally, House of Art), in Munich—these included a photograph of a smiling Patti Smith, Dercon’s notes for a Martin Margiela monograph, and a story about him in a German tabloid newspaper. The headline reads chris dercon is bad-mouthing munich again. “Ha!” he roared. “I’d been complaining about the crazy dogs in the city.”

Let’s hope the dogs are better behaved in London. Dercon has just moved there to become director of Tate Modern, which last year received more visitors (five million) than New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Guggenheim combined. His Munich collage has gone into storage, except for one piece—a quotation from filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard: “Vague ideas must be confronted with clear images.”

On paper Dercon is the ideal candidate to oversee Tate’s international collection of modern and contemporary art. (Its British holdings are housed at Tate Britain, an 18-minute boat ride along the Thames.) The Belgian-born Dercon held top jobs at MoMA PS1 in Queens and the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art and Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam before a dazzling eight years at Haus der Kunst.

At Haus der Kunst, Dercon turned a respectable provincial art museum into a cultural dynamo with epic exhibitions, like the one for which the American artist Paul McCarthy covered the roof with giant inflatable flowers. Haus der Kunst also helped fund the Apichatpong Weerasethakul film Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, which won the Palme d’Or at the 2010 Cannes film festival. And Dercon made international headlines in 2009, when the Chinese artist and political activist Ai Weiwei underwent emergency brain surgery while installing a show at the museum. Ai blamed the Chinese authorities for his injuries, and Dercon issued regular updates on the artist’s condition to assembled TV crews.

“The first time I met Chris, I thought: Wow! So much energy!” said Hans Ulrich Obrist, codirector of the Serpentine Gallery in London. “He’s very entrepreneurial, very courageous, and very innovative. He has done outstanding exhibitions wherever he has worked—really interesting experiments and big blockbusters. It’s very rare to meet someone who can do both, and that’s what Tate Modern needs.”

It also needs Dercon’s dynamism and his zest for cajoling cash from donors now that the museum is planning to double in size. Originally Tate had hoped to open its 92,000-square-foot addition, designed by the Swiss architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, to coincide with the London 2012 Olympics, but the recession struck and the museum couldn’t raise the $350 million in time. Instead, the cavernous oil tanks that once fueled the midcentury power station that houses the main museum are to open next year as film and performance galleries while Tate comes up with the remaining $175 million necessary to complete the project.

“It’s like finally becoming a big producer,” Dercon said, beaming. “It’s great! If you look at the typology of art museums, with a couple of footnotes like the Guggenheim and Centre Pompidou, not much has happened since the Louvre. From the very beginning I’ve thought that there should be a new type of art museum. Tate Modern is the place to do it.”

At 52, Dercon looks not unlike a midcareer James Coburn (if he shopped at Margiela). Tall and tan with short white hair and a beard, he has a rollicking laugh and is prone to theatrical gestures and opening one shirt button too many. His conversation veers from critical theory and an essay he wrote on the future of museums to the joys of soccer, traveling to Beijing with Miuccia Prada, and the exquisite textiles he found in Ethiopia. He is so passionate and knowledgeable that he manages to be endearing even when showing off and name-dropping, both of which he does quite often.

“Chris is a larger-than-life character—a showman,” said Iwona Blazwick, director of the Whitechapel Gallery in London. “He has tons of energy, great charm, huge ambition, and he makes things happen. If he wants to realize a vision, he’ll see it through no matter how crazy and challenging it seems.”

“He is an extraordinarily persuasive and stubborn combatant,” noted Alanna Heiss, founder of PS1, who worked with him there. “Chris will fight to the end to defend his artistic beliefs, and his stamina is great. He is one of the most hands-on people I have ever encountered, and this will be quickly apparent at Tate Modern. He will be found in the ticket office and the cafeteria, rewriting press releases and rehanging whole shows.”

Born in Lier, a quiet city near Antwerp, Dercon is “the eldest and the black sheep” of five children of an engineer father and a mother who taught fashion design. He discovered contemporary art in his teens, and became so obsessed with performance art that he started making it himself. “I was such a bad artist!” he groaned. “So bad that I said: ‘No. Stop.’ And I went to university.”

From 1981 to 1988, Dercon variously tried his hand at selling art, curating, teaching, art criticism, dance, theater, and making documentaries for Belgian television and radio before landing a job at PS1. By 1990 he had returned to Europe, where he founded Witte de With and then became director of the Boijmans. For his first major exhibition there, the German-American conceptual artist Hans Haacke festooned the main galleries with pieces from the museum’s archive to explore the relationship between collecting and displaying. “It was the most fantastic show—a new paradigm on an epic scale,” Blazwick recalled.

As it turned out, it was too new and too epic for the Dutch arts establishment. “I was very unhappy at the Boijmans, and they got very unhappy with me,” Dercon explained. “I was way too young and inexperienced to radicalize an institution so fast.” He left for Haus der Kunst, where his first exhibition featured the Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan’s shrunken sculpture of the man who had commissioned the building in 1933—Adolf Hitler.

“Seeing this hyper-realistic little Hitler was so shocking for everyone because of the history of Haus der Kunst,” said Konstantin Grcic, the Munich-based industrial designer and a close friend of Dercon’s. “We Germans have had to learn how to deal with that period of our history, but it is still problematic. Chris came here as a Belgian, saying, ‘Let’s be honest about it.’”

He roped in Herzog and de Meuron and Rem Koolhaas, a friend of Dercon’s from Rotterdam, to advise him on what to do with the building. The white paint and paneling covering the floors, the Nazi symbolism, and many of the walls were stripped away; the World War II bomb shelter in the basement is being converted into a film and video art gallery. Dercon is to return to Haus der Kunst for the gallery’s opening on April 9, and again in the fall for his grand finale, an exhibition he is curating about another of his “obsessions,” the mid-20th-century Italian designer Carlo Mollino.

At Tate Modern, Dercon faces very different challenges. He spent eight months shuttling between there and Haus der Kunst, getting to know his new team (“incredible”) and the collection (“astonishing treasures”), and has now settled in London, where his partner, the German gallerist Sonja Junkers, will join him this summer. His new institution is not only much bigger than Haus der Kunst but much more successful, critically and commercially, than the latter was when he arrived.

However, Dercon is undaunted by Tate Modern’s massive scale. “That’s the attraction,” he said. “I’ve done difficult things for 100,000 people; now I want to do them for 300,000 or 400,000.” Isn’t he wary of the financial challenge of raising more than $150 million in a deepening UK recession when the government is slashing arts funding? “No! And I’ll tell you why—because I am absolutely addicted to fundraising!”

He will surely face the scrutiny of the voracious British media, which rarely resists poking fun at Tate and is seemingly unable to understand how the museum could have become so successful by taking something as baffling as contemporary art so seriously. He also seems unintimidated by what many in the art world suspect may be his biggest challenge: forging a working relationship with his new boss, the patrician über director Sir Nicholas Serota, whose calculated restraint has so far defined Tate’s public persona and who is known for his intellect and political finesse but not for delegation. “Don’t forget that I’ve had incredibly interesting sparring partners before, like Alanna Heiss—wow!” Dercon said, laughing. “I’m used to being challenged. People expect to be challenged by me. And Nick has known me for 15 years.”

Dercon is elusive about his plans. “Wait and see,” he said. But here are some possible clues. His favorite artists? Both Americans: Richard Tuttle and David Hammons. Favorite buildings? Herzog & de Meuron’s Schaulager in Basel, Switzerland; Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston; and UNStudio’s Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart, Germany. Favorite museums? New York’s MoMA, the Reina Sofía in Madrid, the Kunsthalle in Basel, and the Nationalgalerie in Berlin.

“But for me, museums don’t necessarily have to be museums,” he added. “One of my favorite cultural institutions is the Cinémathèque in Tangier. Another is the National Institute of Design in Ahmadabad, India. Incredible! A museum, a school, a library, a marketplace, and an archive. To plan a new museum, we need to look at them and at science labs, factories, and archives. We need to be daring and courageous and to take risks—really interesting risks.”