This Origin Story of Feminist Art Comes with a Big Asterisk

“Woman. Feminist Avant-garde in the 1970s,” at Vienna’s Mumok, is sprawling and vital, and yet it misses a major part of the story.

In the 1950s, Good Housekeeping provided a few simple guidelines for being a good housewife: Have dinner ready on time. Smile and never complain. Let him know you’re grateful for everything he’s done. And always remember, his topic of conversation is more important than yours.

By the 1960s, the backlash was in full swing. Long-simmering frustrations had roared into a full boil, and soon female artists were mobilizing behind a movement. “For the first time in the history of art, [female artists] started to question the image and representation of women in the art world,” said Gabriele Schor, a Vienna-based curator who’s been building the Austrian power company AG Verbund’s corporate collection around this movement since 2004. More than 300 pieces are on view now through September 3 at Vienna’s Mumok museum, in the potent and vital exhibition “Woman. Feminist Avant-garde in the 1970s.”

During the turbulence of 1968, women dropped the passivity of object for subject in order to subvert the male gaze. This was the era of Austrian artist Valie Export ‘s iconic “Tap and Touch Cinema,” a recurring “action” Export performed during the late ’60s. It’s documented in the exhibition as a black and white video in which Export, wearing a styrofoam box fitted with curtains around her torso, invites strangers to touch her breasts in a public square. They were allowed 33 seconds, and she would look them directly in the eye.

VALIE EXPORT, Die Geburtenmadonna [The Birth Madonna], 1976

“I was trying to develop a completely new, nonvoyeuristic approach to the female body as something other than a visual object […] and confront people with reality,” Export told Interview magazine decades later. “But the fact of the matter is that they just walked away from it.”

The 48 women in Schor’s show, born between 1930 and 1958, pioneered visceral, bodily performance; experimental video; and photographic work in the art world. “Feminist avant-garde” takes off from an exhibition that shook the art world in 2007, Connie Butler’s “WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution” at L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art, but for Schor, putting the two terms together—”avant-garde,” with its false associations with male genius, and “feminism,” with its long history of derision everywhere, despite the extraordinary work that’s been made in its name—places the movement where it’s been left out: the canon of art history.

Strapped for material resources, these feminist artists employed the props and tools they had been assigned—cosmetics, kitchen supplies, endless frustration, and their own bodies, which they bound, stripped, and smeared with paint. Consequently, the same themes reappear in art by women who didn’t know each other’s work at all. For Schor, these fell into overlapping themes: housework, the alter ego, beauty, and female sexuality versus objectification. There’s a huge poster of Lynda Benglis’s famously controversial 1974 Artforum ad in which she’s holding a giant dildo against her naked, oil-slicked body and presenting it to the camera like it was her own appendage. During the ensuing PR firestorm, Artforum editors disavowed it and even quit the magazine. But to a young Cindy Sherman at the time, Benglis’s ad was, as she recalled in the exhibition’s catalogue, “one of the most pivotal points of my career…. She kicked ass!”

Lynda Benglis' `974 ad in Artforum.

Benglis and Sherman have risen to stardom while other artists in the show have enjoyed significantly less recognition. The German artist Renate Eisnegger’s 1974 Hocchaus, a series of photos in which she’s ironing the floor of an endless hall, had no market nor price tag prior to this exhibition. “When I asked her if she still has the work, she said, ‘In 40 years, no one asked for it. I have to look in the attic,’” Schor recalled. “The next day when I called she asked if I’m sure I’m interested.”

An essential truth is that when art history is retold by men, women get left out of the story. Another that this exhibition brings to light, disappointingly, is that the history of women often neglects women of color. Ironically, one work in this predominantly white show was designed as a searing reminder of this: photographs of New York artist Lorraine O’Grady’s Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, an early-’80s performance in which her titular beauty queen alter ego beats herself with a whip while reciting a poem that ends: “BLACK ART MUST TAKE MORE RISKS!” It was a protest against black artists making themselves palatable to white audiences, and against segregation, both in the world of art and feminism.

“As you know, the word ‘feminist’ has had a problematic relationship with black women even at the time of the feminist movement at its height… The programs of mainstream, white feminism were rather to the right or off the center of what the preoccupations of most black women were at the time,” O’Grady told curator Connie Butler in a 2008 radio interview. “Most black women feel that they are dealing with two forms of oppression, racial and gender, and deciding for yourself what the problem is at any given moment.”

Sprawling and visceral, “Feminist Avant-garde” celebrates the courage and experimentation of women who were denied their place in history—and in its omissions, also highlights how many women who continue to be left out.

A Selection of Works From “Woman. Feminist Avant-garde in the 1970s,” at Vienna’s Mumok

BIRGIT JÜRGENSSEN, Hausfrauen-Küchenschürze [Housewives’-Kitchen Apron], 1975

CINDY SHERMAN, Magic Time, 1975/2014

FRANCESCA WOODMAN, Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island, 1975–1978/1997

RENATE BERTLMANN, Zärtlicher Tanz [Tender Dance], 1976

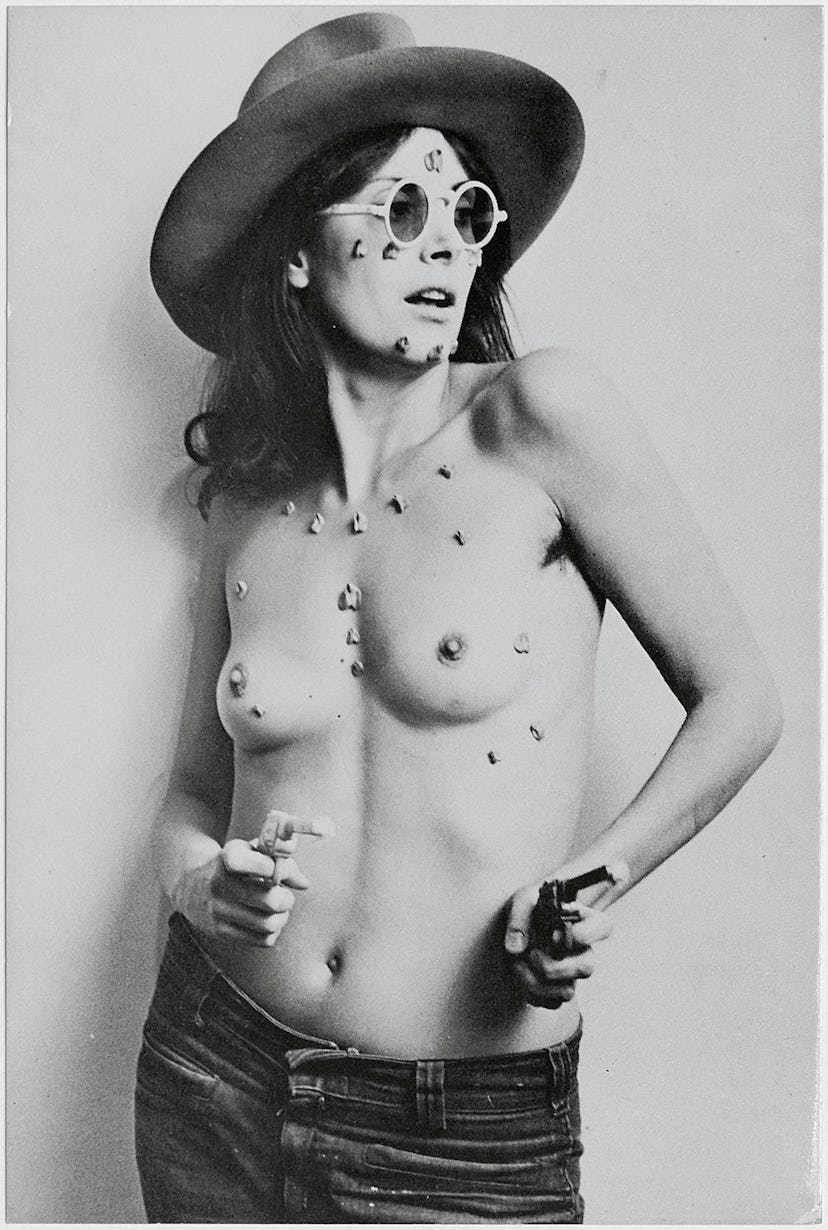

HANNAH WILKE, Super-T-Art, 1974

HANNAH WILKE, S.O.S. Starification Object Series. One of 36 playing cards from mastication box, 1975 Postcard

BIRGIT JÜRGENSSEN, Ohne Titel (Selbst mit Fellchen) [Untitled (Self with Little Fur)], 1974/1977

VALIE EXPORT, Die Geburtenmadonna [The Birth Madonna], 1976

LYNDA BENGLIS, Portfolio with 9 pigment prints

LYNDA BENGLIS, Advert in Artforum Magazine, 1974

Watch 62 fashion insiders speak out on International Women’s Day: