When society club owner Mark Birley’s estate goes up for auction at Sotheby’s London this month, there will be plenty to lure collectors: a William IV console table, Russian imperial porcelain, dog drawings and paintings by David Hockney, Sir Edwin Landseer, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. But perhaps the most personal lot, the item most expressive of Birley as a man, is something a bit more humble: his backgammon set. An avid player who often hosted tournaments at Thurloe Lodge, his 19th-century townhouse a stone’s throw from Harrods, Birley found the clatter of dice unpleasant. As he was not one to put up with even small annoyances, he had a game board custom made by Hermès—in needlework.

Birley, who died in 2007 at 77, built an empire on this drive to gild and refine every detail of his surroundings. At his exclusive members-only clubs and restaurants in London—Annabel’s, Mark’s Club, Harry’s Bar, and George—regulars came to expect beautifully sculpted butter curls, silver-lidded espresso cups, and all of the magnificently starched appurtenances of a first-rate Edwardian country house. “Everything in his life was scrutinized, whether a piece of fruit or a swatch of fabric,” says his longtime friend Min Hogg, founding editor of The World of Interiors. “He took enormous pleasure in finding perfection.”

David Hockney’s Boodgie, 1993, (part of the Sotheby’s auction, as well as all the other artworks and collectibles shown here).

The only son of Sir Oswald and Lady Rhoda Birley, Mark honed his tastes against a backdrop of bohemian splendor, at the family’s villa in London’s St. John’s Wood and their 11th-century rural estate in East Essex, Charleston Manor. Oswald was portraitist to the Court of St. James, tutored Winston Churchill in painting, and traveled the world to memorialize Gandhi, Andrew Mellon, J.P. Morgan, and other magnificos. » Rhoda was a gifted gardener and iconoclastic—not to say barmy—hostess with a circle that included the social powerhouse Sibyl Colefax, the writer Rudyard Kipling, and the diplomat Harold Nicolson. The art historian John Richardson remembers lunching at Charleston Manor, where Rhoda struck him as a “showy, narcissistic character” who poured pots of lovingly made lobster bisque into her rose garden because she believed flowers thrived on shellfish.

She wasn’t nearly as doting when it came to Mark and his sister, Maxime, the mother of the fashion idol Loulou de la Falaise. “It wasn’t so much a strained relationship—more the absence of any normal relationship,” Birley said of his rapport with his mother in an interview in 1990. “An absence of affection…It was rather a mess.”

Scrupulously attired even as a teen and towering over his peers at six feet five, Birley attended Eton and lasted only a year at Oxford before joining the advertising firm J. Walter Thompson, where he replaced the future decorating great David Hicks as paste-up boy and, later, redesigned Tatler magazine. Birley went on to start his own agency, and then shuttered it to open, in 1959, the first Hermès boutique outside France. In 1963, he founded Annabel’s, naming it for his wife, Annabel Vane-Tempest-Stewart, the sparky daughter of the 8th Marquess of Londonderry.

From top: Augustus John’s Robin; The garden at Thurloe Lodge, featured in World of Interiors magazine, 1996.

After three children (Robin, Rupert, and India Jane) and 21 years, the couple divorced, with Annabel publicly branding Mark a “serial adulterer” and the tabloids noting that she had produced two babies with billionaire financier Sir James Goldsmith while still officially Mrs. Birley. The club was far more successful than the marriage. While today Annabel’s has thousands of members who are charged a thousand-pound joining fee and up to the same amount in annual dues, in the beginning it was all People Like Us paying a mere 5 guineas yearly. Founding patrons Lucian Freud, Norman Parkinson, and the 11th Duke of Devonshire were receptacles of Birley’s connoisseurship and obsession with creature comforts.

Though not a designer in any vocational sense, Birley—who buzzed around London in a Bentley with his enormous Rhodesian ridgeback Blitz in the passenger seat—earned the esteem of many of London’s leading interior designers. “The kind of luxury he represented was not necessarily part of English life before Mark,” the interior designer John Stefanidis says. “He always had the best, whether it was bread-and-butter pudding or a special ham from the Abruzzi mountains.”

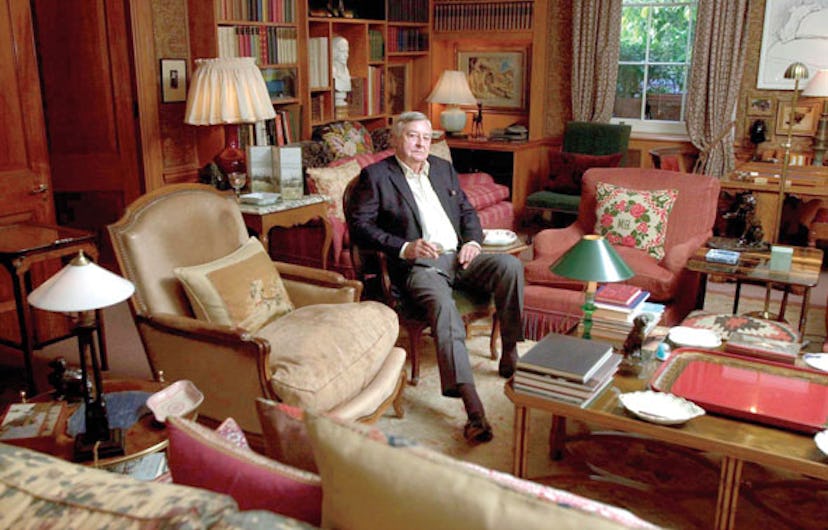

“Mark’s rooms had a certain carelessly grand atmosphere,” the interior designer Nicky Haslam says. “Nan Kempner was staying at Thurloe, which is on a busy road. ‘I don’t hear a thing,’ she said. ‘How do you do it?’ ‘Swansdown,’ Mark replied.” It wasn’t a joke. Birley first used feathers at Harry’s Bar, stirring them into the ceiling plaster to dampen the clamor.

Birley involved himself in every aspect of his clubs, from auditioning wine waiters to making sure the foot baths brimmed with primroses. He was also famously impetuous. In 1970, he started a shop with the decorator Nina Campbell. “Mark wanted to sell Porthault,” Campbell recalls. “I was trying with French friends to get hold of Madame Porthault, but Mark just went into the Paris store one day, threw down his Hermès suitcase, and filled it with things off the shelves, saying, ‘I have a shop in London, and I want to sell your linens.’ It was outrageous, but we got the goods.”

Nicholas Johnson’s A Portrait of Blitz; Rhodesian Ridgeback.

If success begat success for Birley the impresario, as a father he was dogged by tragedy and scandal. Rupert, his eldest child, disappeared while swimming off the coast of West Africa in 1986. In 2006 Birley outraged his son, Robin, and daughter, India Jane—who had been overseeing operation of the clubs when his health began to fail—by selling the establishments shortly before his death for $160 million to the billionaire Richard Caring, who made his fortune in the Hong Kong rag trade. Birley left Thurloe and its contents to India Jane and the bulk of his estate to her son, Eben, now 7, pointedly cutting out Robin, with whom he had a contentious relationship. Robin challenged the will, and brother and sister settled out of court. Last year, Robin opened his own London club, Loulou’s, named for his late cousin. A hurricane of color and pattern, it’s a sort of Annabel’s on uppers, prescribed by Lewis Carroll. The club has been greeted with the same hullabaloo Birley senior’s first venture received exactly 50 years ago.

India Jane, for her part, seems uninterested in continuing “Pup’s” legendary train de vie. She tried living in Thurloe with his table silver, animal bronzes, and humidors, but “the place was too grand,” she says. “I never left the kitchen.” Two years ago she sold the house—a freestanding three-story affair with an acre of land—for, reportedly, north of $25 million. Now she’s unloading its treasures and picking up where the Birley clan left off two generations ago. “Pup sold Charleston to create his life in London,” she says. “When it came back on the market recently, I pounced and bought it. This is one of those full-circle stories.”

Images: World of Interiors: Fritz von der Schulenburg/© The World Of Interiors; all other images courtesy of Sotheby’s London. All Images Courtesy Of Sotheby’s London.