Shape Shifter

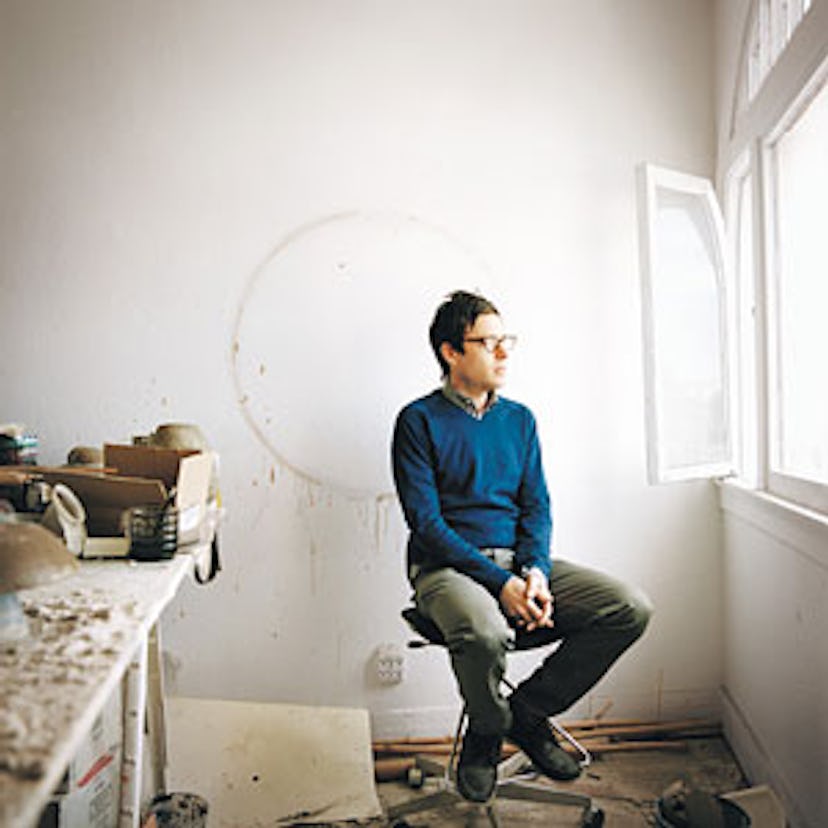

When it comes to conceptual artist Paul Sietsema’s brainy films, there’s more than meets the eye.

Los Angeles artist Paul Sietsema is not a sculptor, exactly, though when he starts a new piece, he works like one: Using paper, wood, glue and paint, he crafts meticulously detailed renderings of wildflowers, scale models of historic rooms and exacting replicas of primitive Oceanic artifacts. But unlike a traditional sculptor, who might set the finished object on a plinth and call it a day, Sietsema then converts his pieces from three dimensions to two. After the work of sculpting is done, the artist films his objects and then projects the footage on a gallery wall. That flickering image—the vision of something that is there and yet not there—is Sietsema’s finished artwork. “I wanted to make sculpture, but there’s something about the way that objects sit next to other objects in the world that I wasn’t entirely interested in,” explains the 39-year-old artist. “Like, it was hard for me to walk into a gallery and look at a painting or a sculpture. There’s something about it that seemed a little archaic, I guess. It’s probably because I grew up watching too much television.”

Sietsema’s newest project, Figure 3, opens at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art on March 28, and if his past work is any indication, it will likely look simpler than the thinking that went into it. During an interview at his Los Angeles studio, the brainy and intense Sietsema unspools a nonstop dissertation on the conceptual content of his art and the sometimes elusive visual residue of all those ideas. One example: For his first major piece, Untitled (Beautiful Place), 1998, Sietsema constructed a series of hyperrealistic plants—he says flowers are “the natural diet of the camera”—and shot them with a variety of dead-stock films as a way to demonstrate “an array of stylistic influences based on the sort of history of photography.” But even the artist himself acknowledges that the effect is “very subtle.”

Nonetheless, museum curators—a subtle bunch—love Sietsema’s work. He’s represented in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney in New York, the Tate in London and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. SFMoMA assistant curator Apsara DiQuinzio calls the upcoming show, which will include a 25-minute film and a group of related objects not in the film, “a much anticipated body of work.”

“Paul is an example of an artist doing all the right things,” says DiQuinzio. “The subject he’s dealing with is the shifting nature of representation. It’s a subject he’s explored in all his projects: how imagery and material alter our understanding of culture.”

Sietsema began drawing and making small sculptures as a youngster. At Berkeley, he studied liberal arts, and after graduation he did odd jobs in San Francisco while establishing himself on the local gallery scene. In 1996 he entered UCLA’s graduate New Genres program, studying with Charles Ray, Chris Burden and Paul McCarthy.

Sietsema has been working on Figure 3 at least since his previous film, Empire, was shown at the Whitney in 2003. The anthropological inspiration for Figure 3, he says, grew directly out of Empire. For that piece, Sietsema constructed the living room of seminal art critic Clement Greenberg as it appeared in a 1964 photo shoot, the same year Andy Warhol made his experimental film Empire, which gave Sietsema his title.

Greenberg’s living room contained various non-Western artworks from Asia and Africa—“the knickknacks of the intellectual”—and as Sietsema duplicated them in miniature, he began thinking about the influence of material on form. For Figure 3, Sietsema reproduced Oceanic artifacts using raw materials that were abundant in his studio—paint and The New York Times.

Given the pace of his work, Sietsema could surely use an extra set of hands to speed up production, but he insists on doing things himself, like a craftsman who is handy at everything but specializes in nothing. “Everybody in a village could all make the same things,” Sietsema muses. “The idea of skill just didn’t exist. Actually, the idea of artistic value didn’t exist, which is an idea I really like.”