In the gift shop of the new Calder Gardens, in Philadelphia, shirts by the art-meets-fashion label Rome Pays Off featuring images of Alexander Calder’s early wire sculptures share shelf space with a new $140 coffee table book, Chess Knightmares, exploring the artist’s little-known work on designing a chess set and his collaborations with Marcel Duchamp. The book features a portfolio of often risqué drawings, such as one of a bishop copping a feel of a bare-bottomed knight—A Bishop Forgets Himself (A Loose Bishop in Duchamp’s Hand)—and images of Calder’s prototype chess set, carved in wood in 1944. His exaggerated blue and red chess pieces will be reproduced soon and offered for sale here for the first time.

It’s hard to know what Calder would have made of this merchandise, at once celebrating and capitalizing on his work. He was, of course, a giant of 20th-century art: a pioneer of abstraction who is often credited as the inventor of the mobile, a painter, a performance artist, and a sculptor whose monumental public art became the backdrop to urban life in the 1960s and ’70s.

Calder worked alone in his studio, without assistants; it was only on his largest sculptures that he had production help. He made some 1,800 unique pieces of jewelry but rejected offers from Tiffany and Cartier to develop a line. “He got pitched all the time,” says his grandson Alexander S.C. Rower, president of the Calder Foundation. “He said, ‘If it’s not made by my hands, it’s not interesting.’” Still, Calder could appreciate a good marketing moment. In the 1970s, he covered a Braniff airliner with his swirling abstract patterns—Flying Colors, the company called it—and painted a race car for BMW, kicking off the German automaker’s long-running art-car program (with ensuing contributions from Frank Stella, Andy Warhol, and Jeff Koons, among many others). Calder eschewed most interviews and generally refused to explain himself. “My work has no meaning,” he insisted as far back as 1931. He was a cultural icon, but also a bit of an enigma until the end of his life.

Calder’s chess set, c. 1942, a gift from the artist to Marcel Duchamp.

But now, 50 years after his death—in 1976, at the age of 78—one of the most groundbreaking, prolific, and widely celebrated American artists of the 20th century is suddenly everywhere, or is about to be. Recent landmark openings in Philadelphia and New York, and a blockbuster show coming in the spring to the Fondation Louis Vuitton, in Paris, are inviting a new generation to seek meaning in, or at least connection with, his kinetic forms. “Calder is an artist you feel you already know, yet every time you encounter his work, you discover something new,” says Jean-Paul Claverie, a longtime adviser to Bernard Arnault, who helps develop programming at the Fondation Louis Vuitton. “There’s a kind of perpetual renewal there that keeps propelling him into the future.”

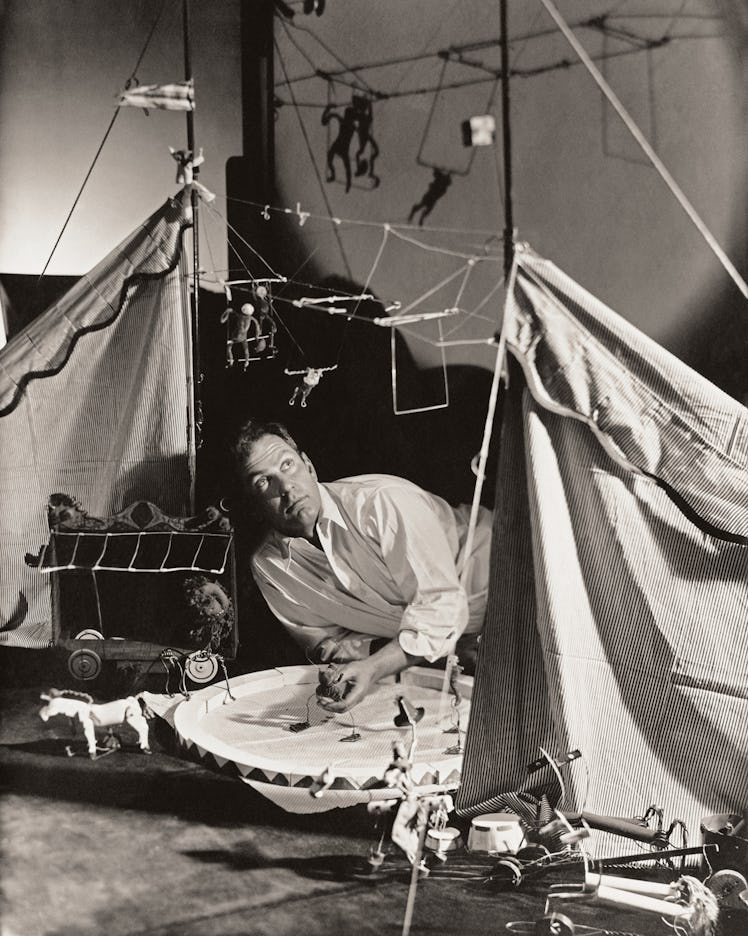

Calder in his studio in Roxbury, Connecticut, c. 1955.

Calder Gardens, which opened in September, is a serene place to commune with the artist in the city of his birth. That’s how Rower describes the Herzog & de Meuron–designed jewel box pavilion—which houses a small rotating display of Calder’s work—and the wild plantings that surround it, courtesy of the Dutch landscape designer Piet Oudolf, which will take a few years to grow. “The whole purpose of Calder Gardens is to get people closer to what my grandfather was trying to communicate, which is really an introspective experience,” says Rower. “A place that’s vibrant and alive, like his work: evolving, moving, never static.”

In October, shortly after Calder Gardens began welcoming visitors, the Whitney Museum of American Art, in New York, opened “High Wire: Calder’s Circus at 100,” commemorating the centennial of one of Calder’s best-known works, his miniature Cirque Calder, which he started in Paris in 1926 and which eventually included several hundred individual components. With its Lilliputian cast of characters forged from cork, wire, rubber, fabric, and string, the circus was meant to be performed; Calder himself put on shows, crouched on the floor over his clowns and acrobats. The work has been a centerpiece of the Whitney’s collection since 1983, when it was acquired after a public fundraising campaign in which Whitney board chairperson Flora Miller Biddle rode an elephant down Madison Avenue.

Calder Gardens, in Philadelphia, which opened in September.

The new Whitney show places Calder as a young artist in Paris, looking to make his way. Along with film footage, there are sketches, hand-printed invitations, and other archival materials showcasing the artist’s broad interest in the world of the circus. “We want to help people make those connections, to really situate Calder’s circus as radical performance art,” says Jennie Goldstein, co-curator of the exhibition. “In the 1920s, performance was not a genre of contemporary art—but he was making this work for fellow artists and art-world people.”

An invitation for Calder’s circus at the 56th Street Galleries, in New York, 1929.

To accompany the Whitney show, which runs through March, designer Emily Adams Bode Aujla conjured a limited-edition capsule collection, sold at the museum shop and at her Bode boutiques. Brooches reference Fanni, the Belly Dancer, and the lion from Calder’s lion tamer act. There is a button-down shirt stitched with antique millinery flowers, crocheted skirts, and boxes inspired by the suitcases in which Calder used to pack his movable circus. “I thought, I can definitely do a T-shirt; that’s obviously important for a museum gift shop,” says the designer. “But I also really wanted to do something that felt more special, like a souvenir you could walk away with from the experience.”

The Calder celebration continues in January, with a display of his BMW art car on its 50th anniversary at Rétromobile, a classic car show in Paris. The Fondation Louis Vuitton retrospective, pegged to the centennial of Calder’s arrival in France in the summer of 1926—when he crossed the Atlantic from New York on a British freighter, at the age of 28—opens on April 16. It will fill Frank Gehry’s undulating museum with some 300 works.

Calder with 21 Feuilles Blanches (1953), 1954.

When Gehry was designing the building, he’d sometimes imagine Calder’s work in it. “It was almost a joke or a dream to say, ‘This space was made for Calder, these volumes are made for Calder, this architecture would enter in dialogue with Calder,’ ” says Claverie, who worked on the building project with Gehry. “Next year, this will become a reality.”

The Fondation will invite dancers to respond to Calder’s work, performing in the museum. Calder’s Cirque will be making the trip over to Paris, along with many rarely seen works, including a room of “Constellations,” delicate wood sculptures created when metal was scarce during World War II. There will be a display of Calder jewelry and photos of the artist by famous friends such as Man Ray and Henri Cartier-Bresson. One area will focus on a single year, 1933, when Calder moved back to New York, and will show his work alongside that of artists in his Parisian orbit, including Jean Arp, Fernand Léger, and Joan Miró.

A postcard depicting an aerial view of Calder’s Le Carroi home and studio in Saché, France, c. 1976.

Calder returned to France after World War II, purchasing a home in the village of Saché, in the Loire Valley, in 1953. He spent long stretches working there through the end of his life—forging deep cultural ties to the country. “He’s very, very familiar to the French,” says Claverie. “He’s, of course, American, but because he spent so much time in France, perhaps a part of him became French.”

Calder originally trained as a mechanical engineer, but he was born to make art. Both his parents were artists who often used their young son as a model. His paternal grandfather, the sculptor Alexander Milne Calder, is responsible for the statue of William Penn atop Philadelphia’s City Hall. Calder studied at the Art Students League, in New York, originally focusing on painting. It was in Paris, working out of a cramped hotel room, that he defined his voice as a sculptor, experimenting with wire, contorting it into human silhouettes and then into geometric shapes.

The artist’s atelier in Saché, 1973.

“Today every kid makes stuff with wire and glass, but this didn’t exist before Calder,” says Rower, walking around the Calder Foundation’s New York headquarters, on the top floor of an early-20th-century commercial building in Chelsea. It’s only here, beyond tightly controlled institutional conditions, that you can experience Calder’s pieces in motion, as the artist intended them to be—swaying because of a gust of wind or a nudge from someone strolling by. “You can’t really appreciate these things in a museum. You don’t have that happening,” says Rower, gently prodding a dangling mobile. “They vibrate; they have a certain activity that’s kind of like aliveness.”

Rower started the foundation in 1987, and two years later opened the former home and studio in Saché. In collaboration with the French Ministry of Culture, he launched the Atelier Calder program, which invites two artists a year to live on the property for three months at a time. “They get the studio and a house and a stipend to come and do a new body of work in the countryside,” says Rower. The program, which is ongoing, has hosted art world luminaries such as Marina Abramović, Sarah Sze, and Tomás Saraceno.

Calder’s Harps and Heart, c. 1937.

After the Louis Vuitton show closes, in August, the Calder celebration will continue around Saché, with museum exhibitions and outdoor sculptures installed at châteaus across the Loire Valley. The year of Calder wraps up in the northeast of the country, with a final show focused on the performance aspects of Calder’s work, at the Centre Pompidou-Metz. (A standing mobile, Chef d’Orchestre, created in collaboration with the composer Earle Brown in 1964, and designed to be played by professional musicians with accompanying percussion, will resonate through the Fondation Louis Vuitton in the spring before moving on to the Centre Pompidou-Metz.)

“Calder is a very, very singular artist,” says Claverie of the remarkable output of work. “He started out as an engineer, then devoted himself to exploring balance, playing with space and with lightness. He holds a unique place in the history of art.”