As a child and even through his teenage years, the artist Chase Hall says he was always observant and imaginative. When we meet over Zoom to discuss his debut solo show in Europe—a collection of paintings and portraiture titled Clouds in My Coffee on view at Galerie Eva Presenhuber in Zurich through April 9—it’s easy to imagine a young Hall dreaming up storybook tales based on the world around him. In conversation, Hall openly discusses matters that are clearly very personal to him and which, in turn, influence his work. Despite exhibiting internationally, many of the ideas he’s currently working through are rooted in American history—he explains that the recurring themes of uniforms in his paintings communicate a shared experience, reflecting his examination of how people create understanding among one another.

While Hall describes his process for these works as particular to the circumstances of the past year, their ideas exist outside of politics, racism, and the pandemic. They are timeless because of the histories they encompass—Hall works specifically with both cotton and coffee, resulting in work that is exuberant in spite of the extractive histories their materials show.

Over the most generous screen-share walk-through that only Hall could lead, the artist discusses his arresting, large-scale new works at Galerie Eva Presenhuber, the process of character development and narrative building that goes into each one, and working to articulate the inarticulable.

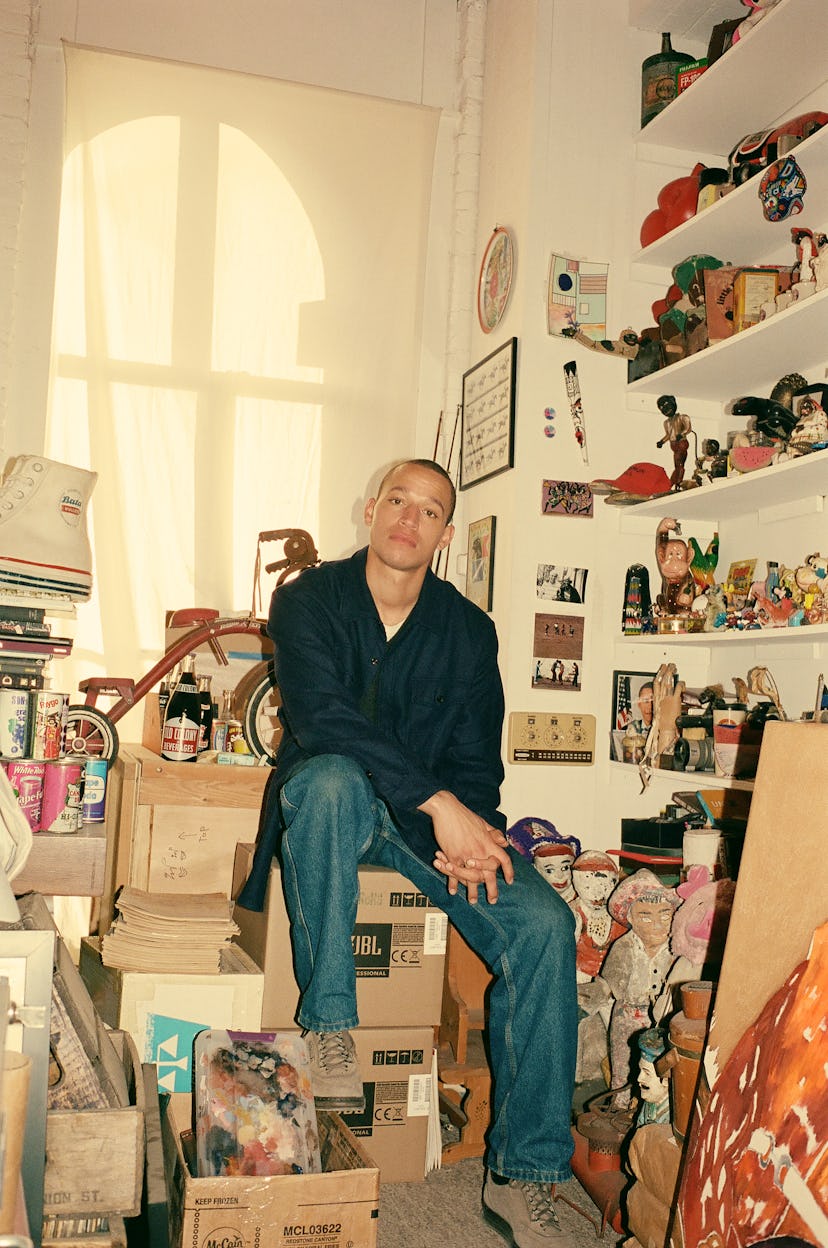

Chase Hall in his studio.

Does your debut European solo show being held in Switzerland bear any significance?

I don’t think the show’s location has played much of a role. I work in a way where I am up early and up late, working every day and editing together work that I feel can be a selection that’s successful to me and has a through-line. I attempt to work through some of these ideas, not only contesting with different languages literally, but also in dialogue with different relationships to history, material, and place.

I’ve been thinking about painting and its relationship to Fred Moten’s idea of Black improvisation— these innate gestures and actions culminating in a painting. The work in the show engages with that feeling of being in your zone, understanding your story, being and becoming and trusting your internal discussion, and I am sure these syntheses have helped me develop into a better human and artist.

Chase Hall

I’ve always appreciated the titling of your works.—they so often bring the viewer right into the action and into the narrative. One that comes to mind in particular is Told you he ain’t comin.

I believe titles have been a way to give a bit of an origin story—a title can create a riddle or an Easter egg for someone to notice or consider. I’ve always been interested in the malleability of language. There can be a bit of poetry and a bit of audacity and a bit of truth, all in a small arena. It’s a lot easier to decide on three words than it is to decide, you know, a book’s worth [laughs]. For me, that’s an area to feel creative outside of the physical creation.

A lot of this work has been about thinking through a different sense of individualism and the steps it takes to become a greater version of yourself: finding value and purpose in life in a way that is more individualized, and understanding what that means. Even in the humility, even in the shame, the haunt and my own fears, overall, I am more focused on making life more legible.

“Told you he ain’t comin” (2021) by Chase Hall. Acrylic and coffee on cotton canvas. © Chase Hall. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber.

The title of the show is Clouds in My Coffee. Could you speak about your process of using coffee as material?

Clouds in My Coffee is the relationship to complications of something clouding your Blackness. I moved most of my life across America—and it is also a nod to my mom always blasting oldies and the fine line between a road trip for leisure versus a road trip for safety.

I’ve been able to develop spectrums of browns out of a single bean. It’s been years of trying to test and experiment. I’ve been tinkering more with its coarseness to fineness in terms of how I’m actually grinding it and creating the pigments. There are different ways that I use it, whether it's a filter drip coffee or a stovetop coffee or an espresso machine. And in terms of the materiality itself, asking how coffee can complicate the ideas of exhaustion, as a seed coming from Africa and being exploited into this addictive drink, that’s commodified as an attempt to battle exhaustion.

Tell me about the process of making these works.

For this show, I’ve been more focused on the paint coming off the brush as well as where it’s actually not touching at all. I understand what I am questioning in my practice, and I am now more focused on how I need to leave it all in the work. I started experimenting with different printmaking techniques and that has allowed me to expand areas of the painting. I have been able to achieve textures on clothing like shearling; I’m using a lot of scrape techniques, a lot of different knives and methods of peeling back paint. I think about cloud formations, ideas of pareidolia and Rorschach testing to create hidden engagements in the work.

“Spelling Bee (Eureka)” (2022) by Chase Hall. Acrylic and coffee on cotton canvas. © Chase Hall. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber.

The material that I continue to question is the cotton canvas itself. Painting with the voids of canvas is an attempt to understand cotton as a conceptual white paint. Cotton acts as light, it acts as emptiness, and it acts as a conceptual play on how this material is showing its weighted history. Oscillating between the cotton as material and coffee as material allows me to animate these hidden figures and faces. There’s a lot that excites me in these gestural abstractions that help share parts of the image, my own personal history, and of the greater questions in my practice.

The cotton and the bean speak on the hybridity of Mixedness. I’m navigating the reality of being Black, but having these moments of humility; moments of genetic confusion, as well as the question of where do you land on the scale of Black to white. Whiteness is an absolute and Blackness is not monolithic. I’m attempting to speak on the space I know, regardless of the longing for a racial absolute.

What have these new paintings taught you?

Painting has allowed me to start articulating the inarticulable, especially when it comes to questioning the idea of pareidolia, which is the phenomenon of when you envision things in the nothingness of something. So an outlet could look like a frowning face, or you can see a dragon in the clouds—your internal psyche is starting to project these imaginations. In this white space, in this cotton space, in this emptiness, that’s where I’m trying to create space for my own deepest critiques but also my deepest traces of memory and fear.

I can imagine this aspect of the work being particularly moving when seeing these works all together.

I’ve been trying to trust that the feelings I feel are very individual and very personal, but are actually very shared. It reminds me of jazz or freestyle rapping—you are able to express your own truth and see what comes from that. Revisiting music or films allows me to reconsider the obvious but also the peripheral, the things you miss. I believe it continues to unfold as you develop a closer relationship to close looking and imagination.

“Damned if I do, Damned if I don’t” (2021) by Chase Hall. Acrylic and coffee on cotton canvas. © Chase Hall Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber.

The process you describe for each work is very intimate. How much are these explorations related to your own personal experiences?

By painting a lot of the subjects in tailored outfits or workwear or different suiting, I’m attempting to show the importance of this chosen armor. There are references of people I admire and sharing a version of yourself. Through labor there is definitely an opportunity to think more about workwear, as a journey or quest that you’re working through. In order to become the next step of yourself, what are some of these crossroads or paths that you have to consider? The work allows you to consider this kind of honorable feeling you feel looking at a family photo of your grandfather, or looking at images of families in front of their first home. On the surface it is stoic, it is respectable—but past the obvious the depth, perseverance and relentless journey is what manifests itself in the coded languages that culminate in my work.

Articulating my concerns is an attempt to consider my younger self: someone who loves history, people, stories, clothing, sports, and mostly the opportunity to learn and question. It is an attempt at building language outside of the literal black and white.