Emily St. John Mandel Steps Into Her Own Multiverse

The Station Eleven author discusses her sixth novel, Sea of Tranquility—which features time travelers and more pandemics.

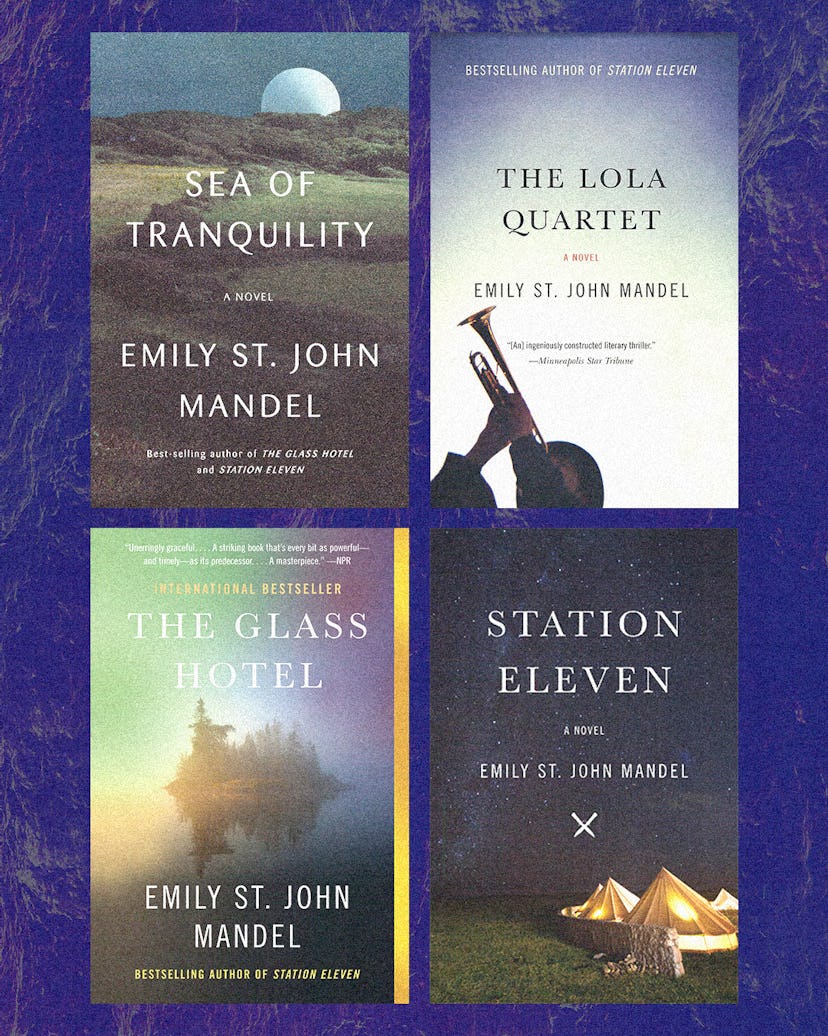

In March 2020—a period that feels like it could be either an eon ago, or yesterday, or both—the author Emily St. John Mandel released her fifth novel, The Glass Hotel. A study of the constellation of people adjacent to and implicated in a massive Ponzi scheme, the book also features a handful of characters familiar to those acquainted with Mandel’s previous work: the shipping executives Leon Prevant and Miranda Carroll, from Station Eleven; the fraudulent investor Jonathan Alkaitis, from The Lola Quartet.

“I’m very interested in group dynamics,” Mandel says. “The way people kind of bump up against each other.” The author’s knack for pulling at the threads of connection both within and across her works, and their uncanny reflection, in turn, of contemporary themes (like, say, scams, or global pandemics and their fallout)—has earned her a reputation as something of a prophet. Her fourth novel, Station Eleven—the pandemic novel—was recently adapted into a hit HBO miniseries with Mackenzie Davis. And her newest, Sea of Tranquility (out April 5), finds her entering another pocket of the zeitgeist: the theory (aptly called the simulation hypothesis) that what we experience as reality is in fact an immersive virtual simulation.

Sea of Tranquility arcs over a 500-year timeline from 1912 to 2401 and back again—a structure Mandel borrowed from David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, one of her favorites—as a contingent of far-future time travelers investigate a possible “file corruption” that could prove the simulation hypothesis. Is a glitch revealing the flickering edges of the simulation? Or has reality simply broken? “That’s the fun thing about the simulation theory,” Mandel told me on a recent March morning. “You can find very smart people making very strong arguments for and against.” And while certain characters from previous works do crop up again—Paul Smith and Mirella Kessler, both introduced in The Glass Hotel, appear in Sea of Tranquility’s year 2020—the new novel also finds Mandel writing herself into the possible world she’s created, via an authorial avatar named Olive Llewellyn, who embarks on a book tour in the year 2203 to promote a new edition of a novel that has been lately adapted into a movie, just as the first wave of a pandemic is cresting.

While Mandel was on a trip to Los Angeles for a “secret TV project,” we spoke over video chat about autofiction, time travel, and voyages to the moon.

How did the seed for Sea of Tranquility get planted?

A very weird seed of a very strange book. My book The Glass Hotel came out in March 2020, and in the months before publication, I’d started to play around with autofiction. I’d been wanting to write about the experience of the long-haul book tour, which is both an incredible privilege and a very weird, very specific kind of business trip. Then Covid hit, and it lent me a kind of creative recklessness. I thought, why not try things that I never thought I’d try before? Everything’s awful, so I’m just going to write whatever I want. [Laughs.] At the same time, I thought, maybe that’s what the autofiction could be for: Using a sci-fi lens, maybe I could talk about the experience of the approaching pandemic.

I’d also been wanting for a really long time to write a time travel story. But the problem with time travel narratives is that they kind of fall apart under close scrutiny most of the time. Time travel creates an infinite loop, removing both cause and effect and free will from the equation, which is disastrous for fiction. That’s where the simulation hypothesis comes into play. The way to make time travel work for myself, as the writer, was to have a character in the year 2400 saying, ‘We don’t really understand why time travel works as well as it does. We feel like it should always create an infinite loop, and we think maybe the fact that it works at all is evidence that there’s something else going on here and we’re living in a simulation.’

Now that you’re on the other side of experimenting with autofiction, what do you think you got out of it?

The tightrope act of that section is that I feel such incredible gratitude for this life and being able to do this job, and I was really afraid that it would come across as, guys, it’s super hard to be a best-selling novelist on a long tour. That’s not a problem; that’s an opportunity. At the same time, people say the most extraordinary things to me on the road—and I guess by extraordinary I mostly mean sexist. Every interaction is autobiographical in the book. All those things people say to Olive, they said to me. [“I was so confused by your book,” a reader in Dallas tells Olive. “I was just like, Huh? Is the book missing pages?” Later on, a fellow passenger on an airship assumes Olive writes for children.] It was also a really interesting exercise as a novelist of approaching a genre that I really appreciated as a reader. Can you write autofiction, but make it sci-fi? And it does feel like a deepening of something that I think all fiction writers probably do anyway—of course your life is wrapped up in your work. I don’t know that Olive is that much closer to me than Miranda in Station Eleven.

Olive says about midway through: “I’ve never been interested in auto-fiction.”

[Laughs.] I just wanted to be funny. But that was actually me. I had zero interest in writing autofiction until I started playing around with it in late fall, early winter before the pandemic.

I wasn’t sure if that was an effort to distance yourself from her in some way.

Not really. She lives on the moon.

Did seeing the Station Eleven miniseries—and being in the world of what your work looks like on screen—affect how you put together Sea of Tranquility? It feels even more scene-based than some of your previous work.

Yeah, I loved Station Eleven. I think that television has influenced the way I write fiction, but less writing for television or seeing my own work adapted for television than just really good TV. I think that might have started even before Station Eleven. I was kind of blown away by season one of True Detective. I thought that was just storytelling at the highest level. I guess maybe I’d bring it back to that show. I really loved that show. I think it did make me think in a more visual way as I’m constructing scenes.

As someone who was interested in sci-fi as a teen, were there works or ideas that you returned to when you decided you wanted to write sci-fi?

The moon colonies—the bubble, the closed city. In a series of books I remember reading, there was a closed science center where the remnants of humanity lived, and outside was dystopian wilderness. That idea was something that I found myself returning to: What if we’re under domes or in very enclosed spaces with unknown territory—or, in the case of the moon, unlivable territory—outside?

I feel like our language gets a little bit inadequate here. If you think about the word colonization, it’s just so different if you’re talking about displacing indigenous populations versus building a city on a moon. With the moon colonies, I was thinking more about the parallel to the simulation hypothesis, this kind of simulated environment. Then, in the same vein, I feel like the simulation hypothesis speaks to the displacement colonizing, in the sense that it seems to me that a big part of the tragedy of colonialism is it has to do with living inside a false narrative. In Canada, it was this completely false idea that this land was there for the taking. Something about living inside a lie that kind of echoes, for me, the simulation hypothesis.

It also seems like it echoes the themes you’ve been interested in in previous novels—there’s a fair amount of questions like, to what extent can we deceive ourselves? What narrative are we telling ourselves, and is it real, and at whose expense?

Yeah, the condition of knowing and not-knowing at the same time.

The novel spends a lot of time considering what it means to belong to or be exiled from a place or a time. I think during the early pandemic especially it felt like we were unmoored from time—the past two years have passed very strangely—and at the same time, we’ve been very stuck in place. How much were those themes related to the period we were living through?

When I realized a lot of the narrative was going to be set on the moon, I thought I was trying to escape from my apartment, you know? In lockdown conditions, I just wanted to get away. The world became so small in the spring of 2020. I was like, it’s got to be the moon, because anywhere else is too close. I told someone, and they were like, ‘So … it’s a narrative about people living in a very tightly contained situation?’ I was like, darnit. It wasn’t what I was consciously doing!

I have seen the characters that carry over from one book to the next—Jonathan Alkaitis, Mirella, Leon Prevant, Miranda Carroll—referred to as Easter eggs. I feel that term trivializes them in a way—they feel more significant than that. But what motivates them?

I agree. I don’t see them as Easter eggs; I see them as more of a cinematic universe—or a multiverse? The works are in conversation with each other. At first, I liked the sense of order. The more I’ve done it, the more I’ve enjoyed thinking of all of the novels as somehow part of the same massive story. So there are a lot of connections that have become more pronounced as my books have gone on.

Why have they gotten more pronounced?

Sometimes, it just makes sense to bring in characters who I already know into a book. With Sea of Tranquility, I knew that I wanted to write about that period when it felt like we all knew the pandemic was coming, but we were doing things like getting on the subway and hugging people and going into crowded restaurants. We just weren’t making that imaginative leap. I just had these ready-made characters who made sense in 2020 and I wanted to see more of, Mirella and Paul.

That sense of impending doom feels like it permeates the other timelines in the novel too —in the opening, Edwin’s experience of going west is one of sheer environmental dread.

He’s based on one of my great-grandfathers, Newell St. Andrew St. John. He was in the same, very privileged predicament: He was from a wealthy family; he was the recipient of an incredible classical education and would have spoken Greek and Latin; but the law in England back then was that the entire inheritance had to go to the first son. The thing done back then if you were a second or third son was to be shipped off to the “colonies” and just expected to make a go of it. On the one hand, these are wealthy people with a ton of advantages. On the other hand, they were wholly unprepared for anything.

You’ve mentioned that at the beginning of the pandemic people were calling on you to write essays about plagues; last year, someone also asked what you thought about the supply chain issues because logistics are a prominent part of The Glass Hotel. Is there a part of Sea of Tranquility that you think people are going to call on you to prophesize about?

That’s a great question. I don’t think so, although I would say maybe people who are freaked out about how Station Eleven was about a pandemic and The Glass Hotel was about the supply chain, maybe they’ll find Sea of Tranquility reassuring. I think any book that has moon colonies is kind of utopian. That’s not a future that collapses into a wasteland with a traveling Shakespearean theater company. That’s like, Star Trek futurism. That’s the United Federation of Planets and a certain degree of organization and technology. I see it as a very hopeful book—at least compared to the problems in the other two books. Although there are pandemics in it…

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

This article was originally published on