The Unlikely Art World Stars Every Mega Collector Wants to Know

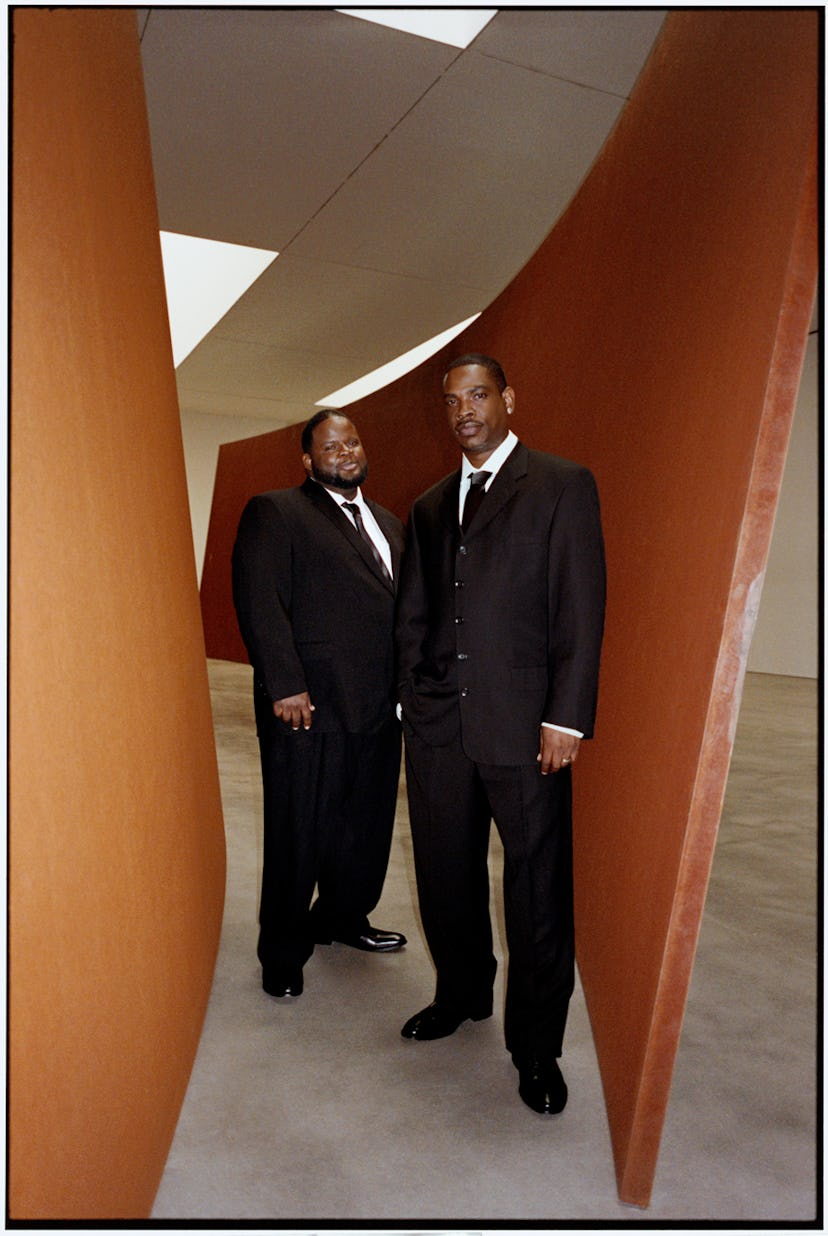

For years, Gagosian’s heads of security, Andre Headley and Anthony Johnson, have protected masterpieces, welcomed billionaires, and become quiet legends in their own right.

The Cady Noland exhibition at Gagosian’s Chelsea gallery this fall was a nightmare for a security professional. The reclusive sculptor often incorporates found objects in her installations, and she is notoriously prickly about how they are placed. In this case, she had covered the gallery’s floor with gargantuan black and white prints and equipment that could have been lifted from a construction site: pipes, white crates, trash cans, and street barricades. Andre Headley and Anthony Johnson, Gagosian’s heads of security, often had to reroute visitors. “Be careful,” Johnson said, as he and Headley steered me through the exhibition on a Tuesday morning. “There’s artwork on the floor.”

“These chairs weren’t really part of the show,” Headley said, nodding at two gray desk chairs tucked by a display table. “But Cady thought it was great to add them.” It fell on Headley and Johnson to ensure visitors respected the intentionally blurry line between multimillion-dollar artworks and items at a government surplus sale. “A little kid sees something like this,” Headley added, pointing to a white Guitar Hero controller, “and he’s like, ‘Mommy, can I go play?’ ”

In their years at the gallery—20 for Headley, 11 for Johnson—they have watched over the works of Pablo Picasso, Willem de Kooning, and Takashi Murakami. Neither Headley nor Johnson had an art background before joining the gallery. Headley, a 43-year-old father of two, grew up in Barbados and moved to Brooklyn with his mom at age 13. In late 2005, he was working security for Diesel when his contracting company referred him to Gagosian. Johnson, a 34-year-old from the Bronx, joined the gallery in 2014, after working in residential security. While Johnson occasionally plays the junior colleague (“He’s Head Head of Security,” he said of Headley), the two usually operate as a team. In conversation, they tend to finish each other’s sentences. At one point, they began to describe Headley’s personal collection of signed art books:

“One is by Richard Prince,” said Headley, “and one is by—”

“—the Ed Ruscha one,” interjected Johnson.

“Yeah, Ed Ruscha,” said Headley. “He had the—”

“I know which one you’re thinking of, with all—”

“—the garages,” they said in unison, referring to the artist’s book of aerial photography, Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles.

Security is their primary responsibility—they are the ultimate enforcers of no touching, no liquids, no video, and no photos of the gallery space—but their role has also taken on a social dimension. “They’re the first faces you see when you walk through the door, setting the tone for everything that follows,” said Derek Blasberg, executive editor of Gagosian Quarterly. “They greet everyone, from big-deal collectors to first-time visitors.” In other words: They are acquainted with many of the characters of the Gagosian universe—a category that includes the likes of billionaires Steve Cohen and David Geffen. Among Gagosian high rollers, one insider said, being “ ‘in’ with Andre and Anthony” is as much a status symbol as buying anything on the walls.

Headley and Johnson were more modest about their influence. “I wouldn’t necessarily say that,” Headley demurred, grinning. “No egos here,” Johnson agreed. But they concede that many potential buyers do court their opinion. “A lot of guests just want to know: ‘With the time you spend with this piece, does it grow on you?’ Or ‘Do you like it more and more each day you see it?’ ” Headley said. “Then they’ll be like, ‘You know what? I was just asking you that because I’m interested in buying it.’ ”

Headley and Johnson are professionally coy about celebrity clients, though the occasional anecdote does slip out. (Of “Avedon 100,” the gallery’s 2023 show for the centennial of Richard Avedon’s birth, Headley said with a wink, “That was my first time meeting A$AP Rocky.”) They’re more comfortable talking about the artists, partly because they have longer relationships with them. Headley remembered how the sculptor Richard Serra, while installing a 2008 exhibition, kept insisting Headley try his hand at photography. “He was like, ‘Hey, man, you’ve been here so long, I think Larry Gagosian should give you a show.’ ”

Both have warm memories of Brice Marden, the minimalist painter who died of cancer in 2023. Marden had been a security guard himself, Johnson noted, at the Jewish Museum in the 1960s. In his last months, Marden had been working on a new exhibition at Gagosian, titled “Let the Painting Make You,” and completed the show’s six large paintings from his wheelchair, finishing the last one just days before his death. The exhibition opened three months later. “That was one of the most emotional shows,” Johnson said. “Everybody was coming to see the artwork. You see them watch the art, and then all of a sudden you just see them crying.”

Johnson said the mood inside the galleries changes according to what’s on view. A few years back, he’d guarded a piece by Duane Hanson, whose hyperrealistic sculptures of average Joes might be described as Studs Terkel meets Madame Tussauds. The one at Gagosian was called Security Guard. Johnson liked to stand beside it, perfectly still. “People used to joke with me,” he said, “like, ‘Which one is the art, and which one is the guard?’”

Grooming by Adrian Alvarado for Dior Beauty at See Management. Photo Assistant: Christopher Smith; retouching: Jodie Herbage; Fashion Assistant: Dylan Gue; tailor: Luis CasCante at Altered Mgmt. artwork: courtesy of Estate of Richard Serra/Artists Rights Society.