Gus Van Sant on Dead Man’s Wire and the New American Fringe

With his first film in seven years—a true-crime saga starring Bill Skarsgård—the director proves he’s as unpredictable as ever.

The filmmaker Gus Van Sant secured his place at the center of American independent cinema by making movies about characters who live on the margins: Matt Dillon as an addict in Drugstore Cowboy (1989); River Phoenix as a hustler in My Own Private Idaho (1991); Matt Damon as a math prodigy working as a janitor in Good Will Hunting (1997). There’s always a strain of romanticism to his stories, of longing and desire to belong, that’s cut with a subversive sense of humor. But Van Sant’s worlds are also haunted by death, from the teenage shooters in Elephant (2003) to the murder of Harvey Milk, one of the first openly gay politicians in America, in the 2008 biopic Milk.

Van Sant’s latest movie, Dead Man’s Wire, explores a new sort of fringe character through the bizarre but true story of Tony Kiritsis, an Indianapolis trailer park manager who unsuccessfully tried to pivot to real estate. In February 1977, after falling behind on mortgage payments, the 44-year-old Kiritsis took one of his bank’s executives, Richard Hall, hostage. As TV crews broadcast the kidnapping, Kiritsis kept police at bay by fastening a shotgun to Hall’s neck with a wire—the “dead man’s wire”—that ensured the captive would be shot if Kiritsis was. What sounds like an edgy, high-concept thriller takes on both comic and tragic dimensions in Van Sant’s hands. Kiritsis, played by Bill Skarsgård, can’t stop running his mouth and undermining his half-baked plan.

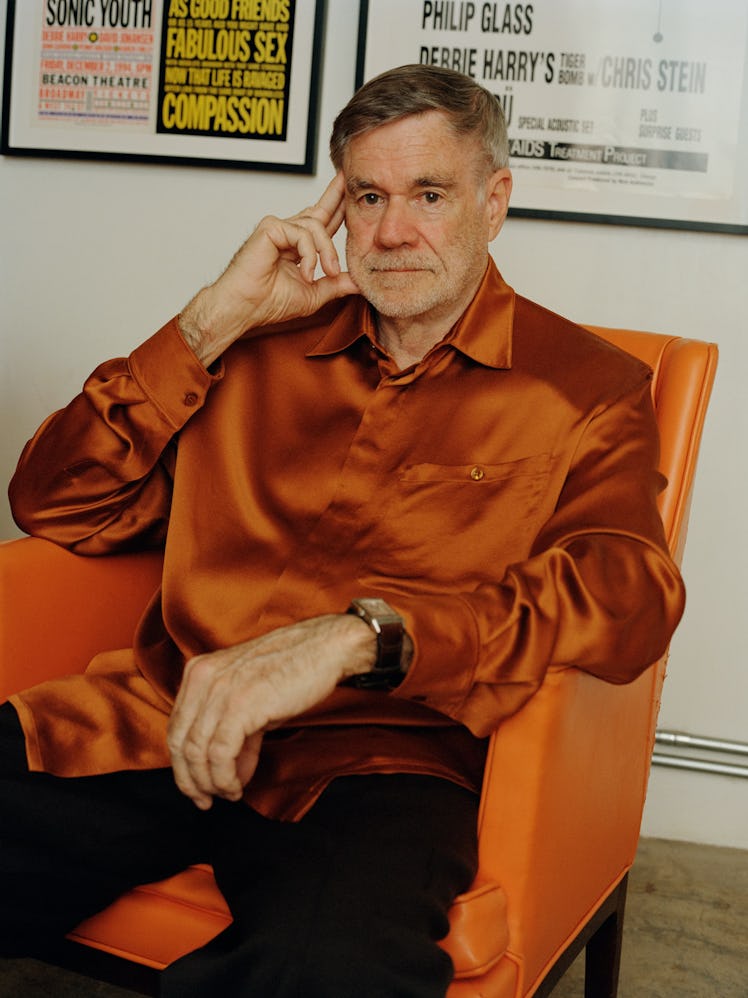

Van Sant didn’t seek out the project—it came to him through a producer he knew, who had funding ready and needed a director. The sheer oddity of Kiritsis’s story captured Van Sant’s imagination. “Most of my films are about people who are antiheroes. You are on their side, but you aren’t exactly rooting for them,” Van Sant said over coffee in Manhattan. At 73, he has a low-key presence and the same boyish sweep of hair he’s maintained for decades. He started shooting Dead Man’s Wire in Louisville, Kentucky, in January 2025, weeks after Luigi Mangione, driven by a “disdain for corporate greed,” had shot United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson on a Midtown street just a couple blocks away from the hotel where we were chatting. A young assistant on the film declared that Mangione deserved a statue in Central Park. “I had never really been presented with that thought process,” said Van Sant. “I still can’t quite get there. I put it down as a generational thing.”

Loewe jacket, hoodie, and pants; Zegna shoes

That’s not Van Sant throwing his hands up at kids today. While his style freely changes from project to project—his follow-up to a conventional movie tends to be an experimental, almost trippy one—his career is defined by portraits of youth. He’s also matter-of-factly explored queer sexuality since making his first feature, Mala Noche (1986), a drama about a young liquor store employee in Portland, Oregon, who is attracted to a Mexican immigrant. The film is widely admired as a harbinger of New Queer Cinema, the wave of 1990s indie films that subverted traditional storytelling and embraced sexual desire with stylistic brio.

Van Sant was born in Louisville but grew up wherever his father, a traveling salesman and clothing manufacturer, took the family for work: Colorado, Illinois, California, Connecticut, Oregon. “Changing locations as many times as I did, I was pushed to identify the culture in different places, to pick up on habits and fads and things,” he explained. At 16, while in New York working for his father’s clothing company, Van Sant bought a camera. Initially, he was interested in painting, but he noticed that many painters weren’t able to make a living. He shifted to film and attended the Rhode Island School of Design in the 1970s, inspired partly by Pink Flamingos, John Waters’s low-budget, anything-goes classic. As a student, he traveled to Rome on a study program. “We saw [Federico] Fellini making Casanova,” he said. “We watched [Pier Paolo] Pasolini at the dubbing stage of Salò and visited his home in the ruins of a castle.”

Ferragamo jacket, pants, and shoes; Charvet shirt.

Van Sant’s oeuvre leans more toward Pasolini’s street narratives than Fellini’s fantasias. “Almost all of my work is based on reality,” he said. One of his first shorts was called The Discipline of D.E. (1982), a humorous guide to gliding through life with minimal stress, adapted from a William S. Burroughs story. Van Sant bought the rights by visiting Burroughs, whose legendary Beat novels had grabbed him with their mix of dirty realism and avant-garde abstraction. Later, he collaborated with the writer, casting Burroughs in Drugstore Cowboy, composing the music for Burroughs’s spoken-word album The Elvis of Letters, and directing him in the short William Burroughs: Thanksgiving Prayer. In fact, the shoot for this story took place at Burroughs’s old apartment in Lower Manhattan, which the gun-toting author nicknamed the Bunker, and where Van Sant met with him in the 1990s.

Van Sant’s own outsider streak has persisted throughout his career, down to his choice to live primarily in Portland, not Hollywood. At first, he was on the outside by necessity: Mala Noche was made with around $25,000 of his own money, saved from New York advertising gigs. But he was never interested in following a traditional path. After My Own Private Idaho made him a director to watch, and he landed his first of two Oscar nominations for best director, for Good Will Hunting, he made the unorthodox decision to create a shot-for-shot remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. It baffled critics and sank like a stone. The film felt like a personal experiment: Van Sant knew that ’90s Hollywood had remake fever, and the idea of a Hitchcock color redo harked back to his days at art school, when he was interested in ideas of appropriation. It was also, bless the man, what-if artistic curiosity.

Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello shirt and pants; Jaeger-LeCoultre watch.

Dead Man’s Wire is Van Sant’s first feature since Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot, his 2018 portrait of the quadriplegic cartoonist John Callahan. During the past seven years, Van Sant has returned to painting, staged a few art and photo exhibitions, and forayed into television, directing most of Ryan Murphy’s 2024 series Feud: Capote vs. the Swans, a drama about Truman Capote’s falling out with a group of New York socialites. He’d noticed Murphy had stuck with a stable of directors, and proposed himself as a new addition.

In the long run, Van Sant’s creative instincts have served him well—he goes with the flow when it makes sense, and does what’s artistically right for him. “You have to react to what is on set to make your final decision about what the ‘style’ of the movie is,” he said, recalling how, on Drugstore Cowboy, he tossed 30 pages of storyboarded scenes on the first day of shooting once he realized they wouldn’t be feasible for the crew. Van Sant recalled the easygoing casting process for Dead Man’s Wire with his producer, Cassian Elwes. “Cassian would just say, ‘Oh, Colman [Domingo] says he wants to play Fred [a DJ involved in hostage negotiations].’ And we were like, ‘Great!’ And he did it. And then Cassian would go, ‘Oh, I think we might be able to get Al Pacino to be the bank president.’ And we were like, ‘Great!’ ”

Needless to say, there’s no guessing what Van Sant’s next film might be.

Grooming by Inna Shats for ORIBE. Photo Assistant: Storm Harper; Fashion Assistant: Elissa Dziersk; Tailor: Lindsay Wright; Special Thanks to Giorno Poetry Systems.