Hayv Kahraman is best known for painting women with prominent eyebrows and dark hair, often contorted in surrealist poses. In “Ghost Fires,” her latest solo show at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York City’s Chelsea neighborhood, wisps of smoke rise from her subjects’ fingertips, and they have no pupils in their eyes. Several paintings feature a fine layer of loosely woven flax and marbled black-and-red pigment, a texture that appears scorched, or like bandages fraying off of a wound. “That’s something that I really feel and think of the world,” the artist recently told W. “Shit is falling apart.”

“Ghost Fires” is Kahraman’s first body of work since Los Angeles’s devastating January wildfires, which displaced the artist and her family along with thousands of others. While the compositions radiate with anguish, they do not depict any literal fires, but instead white plumes with a spectral translucency. Although fires themselves are ephemeral, “they haunt,” Kahraman explains, leaving behind a trail of ghosts. They linger in the form of smoke, or the sheen of toxins left on everything they touch—the remains of Kahraman’s Altadena home are coated in unlivable amounts of lead, other heavy metals, and arsenic. Ghosts can also store themselves as memories, or deeper in the subconscious, resurfacing at unexpected times.

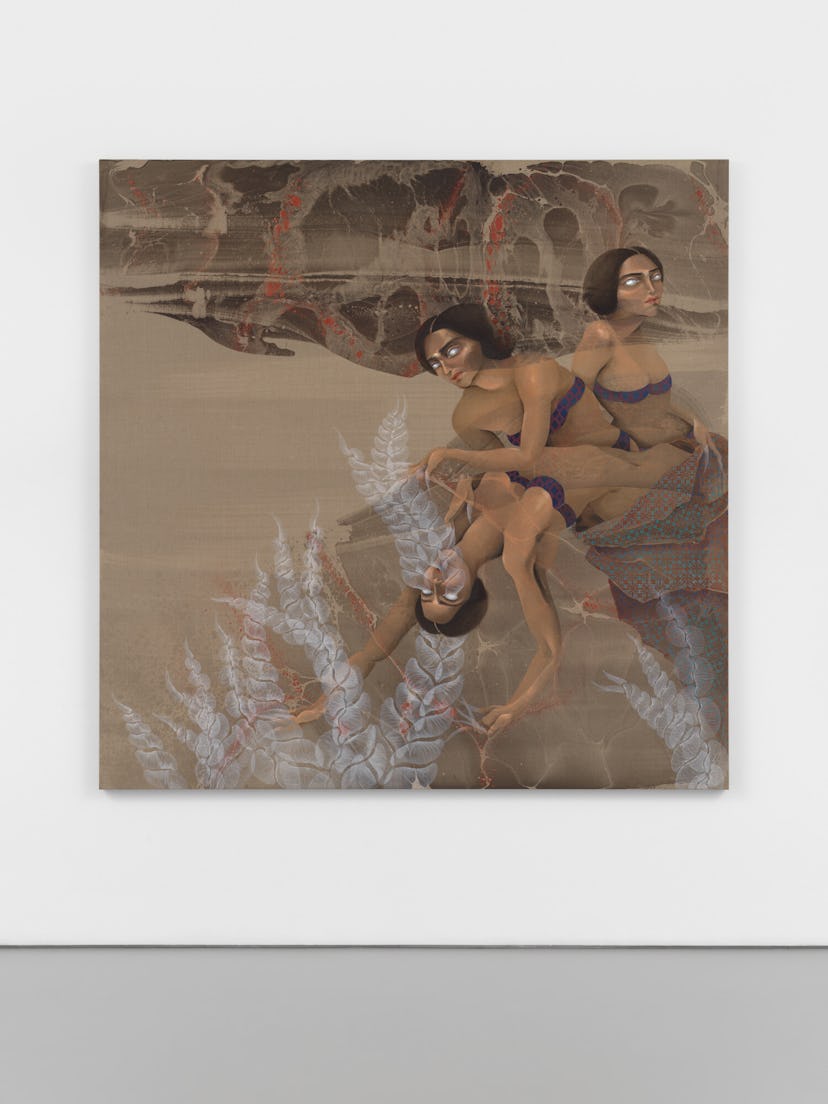

Hayv Kahraman, Ghost Fires, 2025

On the night of the Eaton Fires, Kahraman saw the flames from her daughter’s bedroom window and felt instantly transported to the past. She suddenly found herself in her childhood bedroom in Baghdad, where she had watched air raids falling from the sky. “I was 10 years old,” Kahraman recalls, the same age that her daughter is now.

Having moved to Altadena in 2022, Kahraman was born in Baghdad in 1981, and fled Iraq with her family during the Gulf War in 1991. Although she has few conscious memories of the war, recurring similarities with the fire have unwittingly forced her to relive them. When Kahraman drove back to her home the morning after the fire, the charred rubble on the ground and devastation in her neighbors’ eyes closely resembled the remnants of war. Scorched palm trees summoned images of the family orchard in Iraq, and active flames still burned in the streets. As a fire department helicopter passed overhead, opening its hatch to release water to the ground below, Kahraman instinctively dove to the floor in terror, imagining it would drop a bomb. “The problem is, I can’t connect that reaction to an actual memory,” she says. “My brain has somehow decided to lock that time away.” Feelings she cannot rationalize or put into words exist more as a visceral sensation, she adds. “It’s an embodied sense of fear.”

Hayv Kahraman, Rain Birds Ritual, 2025

Having lived with complex PTSD for the majority of her life, Kahrman was already familiar with the debilitating effects of depression. After the fire, it overcame her with a severity she had never experienced. She had plowed through the first months after the disaster, on a mission to secure the logistics of insurance, housing, and a new school for her daughter. It was the moment she had the opportunity to rest that depression struck her all at once. “I fully detached from reality,” she says. “I didn’t want to get out of bed. I didn’t want to eat.”

Her studio, thankfully, had been unaffected, and after several debilitating weeks, she emerged from the worst of her depression to attempt to paint. “I don’t know how I made it to my studio, but I did,” Kahraman says. After sweeping the floor and picking up a brush, it took about half an hour for her true sense of self to start creeping back in. “It truly felt like this door appeared in front of me, and I opened it, and walked through,” she said. The marbling process—dipping the canvas into a water bath layered with pigments—was especially therapeutic. “I am very controlled in the way I make work, and this was a way to relinquish control of the final outcome,” she says. “The tiniest speck of dust in the studio will change how the pigment moves on the water.”

Hayv Kahraman, Anqa’, 2025

While her Altadena home is still standing, there’s a long road ahead before it can be livable again. In the meantime, Kahraman and her family were able to find an apartment farther east in Los Angeles, “away from the toxins, and closer to her studio,” she says, and where her daughter loves her new school. Recognizing herself as both a war refugee and now also a climate refugee, Kahraman reflects for a moment on how one devastation can prepare you for the next. “I still manage to go on with life. That’s something that I know very well.” In her artist’s statement for “Ghost Fires,” she recounted returning to her Altadena home and finding the cacti in her yard the healthiest it had ever been. “It became glaringly obvious,” she wrote, “that this devastation also brought life, perhaps even the emergence of another world.”