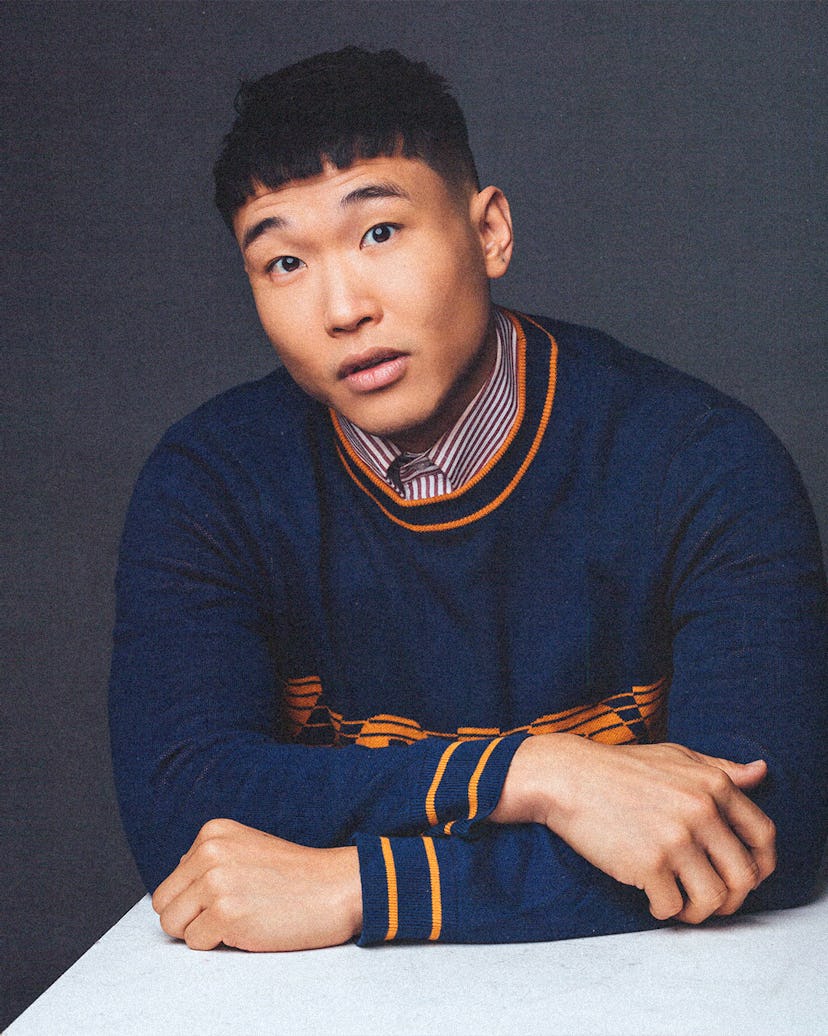

It is relatively unusual to see Joel Kim Booster stare off into the middle distance. But in Fire Island, the film he wrote, executive produced, and stars in, we see him lose his gaze in a mix of wonder and yearning, his eyes wandering on the ferry to the Fire Island Pines. Later, through a glass window watching friends, he surveys a neon-soaked underwear party. Before this performance, Booster’s stage presence depended on what he has described as a “Hot Idiot” persona: libidinally driven, yet astute in his observations; mockingly facile, but self-assured; cheekily illiterate, but also, as one character in Fire Island says with admiration, “biting.” It’s a clever costume and putting it on has been a useful kind of drag in the last decade or so of Booster’s career, but Fire Island lets him add another dimension.

Booster, born in South Korea and adopted into a white family in Illinois, got his start in standup in Chicago and then moved to New York, his name steadily rising with his queer peers. It was in the endless runs of open mics and shows that this flippant and appealingly glib persona emerged. Booster’s stage persona then became accessible on a national level when he appeared on Conan in 2016. (“I literally knew I was gay before I was Asian,” he jokes both bluntly and with a whiff of performed naïveté.)

When I speak with Booster on Zoom, he elaborates on how the funny and discriminating Hot Idiot character has allowed him some critical distance: “I think I created that persona as a form of protection.” The Hot Idiot, or himbo per our common parlance, has usually been the province of white and mostly straight men; for Booster, it was a chance to be subversive, “a fresh take on being an Asian man” that could raise a middle finger to the fraught politics of Asian-American masculinity—while sipping on a vodka soda and getting laughs with precisely-structured jokes.

Now, before the premiere of his Amy Heckerling-esque riff on Pride and Prejudice, his first Netflix special called PsychoSexual, and a role on the upcoming Maya Rudolph-led Apple TV+ series Loot, Booster is “back[ing] off” of that “bimboy” persona. “You always want to stay two steps ahead of where the cultural conversation is,” he says. Pop culture is reaching a himbo saturation point, and it’s been a part of Booster’s act for so long that it’s become what people expect of him. Fire Island, brash not only in its approach to the social dynamics of gay male culture, but also in its sensitivity and tenderness, allows Booster to move from his initial confrontational character and unsheathe himself. In this film, he can be sexy, hot, powerful, and vulnerable—all made possible because of the actor’s vulnerability. “This movie and the special are much closer to who I actually am at my core as a person. Removing that layer of protection—of, Oh, I'm just stupid—has been really scary,” Booster says.

Booster is evolving his persona at an interesting time, tossing away a set of tools that essentially welded his success. He has asserted himself as attractive, queer, and the object of people’s desire—but only as long as there’s something slightly disarming about it. He figured that if he sandwiched himself between self-assuredness and a scintillating appearance, a wider audience outside of queer Asian people would not be threatened by him. This isn’t inherently a problem, but Booster’s approach offers a solution to a question: how can one negotiate the ways the culture perceives queer people and Asian people, and find the right kind of paradox that’s engaging and consumable? There are relatively few contemporary Asian-American sex symbols, fewer of whom are queer, and even fewer developed their public identity as a parody of that idea. On one hand, Booster's bit suggests that it's precarious to consume him; on the other, he encourages you to do it anyway.

It was Booster’s observations on gay culture that brought him here. Eight years ago, he and Bowen Yang (who co-stars in his film as Howie, the Jane to Booster’s Lizzie) went to Fire Island. Booster brought a copy of Pride and Prejudice, found Jane Austen’s observations of class and society a good map for how (mostly) cis gay men treat each other, wrote an essay about it that has been lost to the Internet, and was later convinced by his agent to turn it into something bigger. The project moved from Quibi to Searchlight and Hulu, and it has demanded of Booster not just a fun and free approach to riffing on Austen, but a more serious examination of himself, with essential collaboration from acclaimed Spa Night filmmaker Andrew Ahn, who directed Fire Island. Ahn told me that interrogating Booster’s vulnerability was a crucial part of the process: “It’s an aspect of Joel’s own personality that we kind of pulled out and magnified.”

Booster is aware of the scrutiny that comes with exposure as a queer Asian-American man, having discussed capital R-representation before, albeit on a level that felt much less on his terms and more out of obligation. He says in our conversation that, at the time of our Zoom call, only two queer Asian journalists are interviewing him, including me, which makes him more inclined to be candid. The topic of queer Asian desirability can hold more power between two queer Asians who are both children of adoption, and we discuss how, in his work, Booster problematizes questions around representation instead of settling for bland tokenism.

The actor is introspective and engaging, aware of his artistic evolution without seeming self-conscious. It’s a sparkling reminder of his confidence, as are scenes in Fire Island, like one where his Lizzie Bennett (here, named Noah) argues with his Mr. Darcy (a lawyer named Will, played by Conrad Ricamora) about a short story in Alice Munro’s Runaway. In this frequent balancing of what Booster says is a “heightened version” of himself and this more exposed person, Fire Island explores territory beyond straightforward romantic comedy conventions. The film challenges our preconception of Booster, finding its most striking moments in understatement. It balances pensive looks with Noah’s introspection, and gives us a peek inside of Booster’s head, too.

“The difference between me and Noah is that if I were doing a movie about me, so much of it would be behind the curtain,” Booster says. “Noah is much more apt to speak what is going on in his mind than I am, as satisfying as it is for me to be right.” I see the gears in his head turning, the ones that fuel the attention to detail that he builds into his stand up sets. “I'm constantly making observations; it’s the reason I’m a writer in the first place,” he tells me.

Booster is highly aware of the surveillance he’s under as the object of his film’s gaze. He tells me about going to the gym for himself, instead of going for other people. He didn’t exercise at a gym while filming Fire Island, finding it scary to be shirtless, and says it brought him back to darker moments of his past when he was, as Noah says in the movie, giving power away to other people. He dips into an occurrence that happened while filming on the island, when he overheard two passersby discussing the film shoot. “One guy pointed at me and said, ‘And that's the lead.’ The other guy said, ‘That's the lead?’” Booster recounted. “I was so rocked by that moment.

“I wrote this movie because I thought I had moved past all of those insecurities,” he says. “And then in one moment, it all came rushing back, because suddenly, I was like, Oh, my god, many people are going to see my body. I'm supposed to be the leading man, but is that how I see myself?”

Making the film (and tripping on LSD during one Fire Island adventure) helped Booster to see himself from a more objective place. He also feels that the ability to access those parts of himself, particularly the most sensitive ones, would not have been possible without Ahn. The director, who has received accolades for his thoughtful, probing, simmering dramas of Asian-American and queer life in films like Spa Night and Driveways, was a key ingredient to Fire Island’s point of view. “I really can't imagine doing this with anybody but Andrew,” Booster says. “It's such a specific story and such a personal story about being gay and Asian that it only made sense to have a gay Asian director to collaborate with on this. He really was the ideal shepherd to lead us through those moments. Because he understands what our experiences are on a really intrinsic level.”

Ahn’s (and cinematographer Felipe Vara de Rey) camera loves Booster: he shimmers in natural light and his gaze pierces through a crowd, but the lens betrays Noah’s loneliness and uncertainty of how to situate himself within queer happiness, in the context of a gay culture that reifies other social caste systems and structures of desirability. Early in the film, when Noah narrates his ferry ride from off-screen, a note in his voice lingers. “We’re invisible to these people,” he says, toggling between intellectually sustained derision and the more human desire to belong, even to a (white, gay) social landscape that doesn’t have a place for him.

Although Booster has moved away from writing about his adoption in his material, he admits its inevitable influence on making Fire Island. “I've always felt like an outsider, in my own family, too, which is why the chosen family aspect of this film is so important,” Booster says. “Chosen family has always been deeply important to me, but I especially have felt sort of outside looking in for my entire life, on both the Asian experience and just every experience [being] filtered through this feeling of being one or two steps removed from everything. This movie is in large part about that feeling. Even if it's not explicitly about the experience of being adopted, it is like the experience of being outside of something.”

But Fire Island is about being inside of something, too. It’s about the solace you can find when you stop longing for the space that doesn’t want you and commit to the joy of embracing your people, your community. The events of the film are mostly recollections and amalgamations of a past self for Booster, and Noah’s arc reveals an evolution of how he navigates himself and the society around him. Most importantly, though, it’s about how he contextualizes himself within the community that cares about him. Fire Island, and Booster, even in transition between public personas, finds the thrill in that communal embrace. What does queer joy and happiness look like to Booster? “It looks like the very last scene of dancing [with friends] on the dock of Fire Island. It's reckless and hopeful. That is what queer joy looks like to me.”

This article was originally published on