At the root of conceptual artist Lamar Robillard’s interdisciplinary practice lies a crucial ethos: resistance. Whether the Brooklyn native is resisting oppressive modes of thinking, institutions within the art world, or those establishments in larger society, Robillard uses his work as a way to challenge mainstream notions of visibility, nonconformity, and spirituality—so much so, in fact, that the artist sees his work as a way to connect with divinity. In his pieces, Robillard engages primarily with sculpture and assemblage, working in the tradition of artists like Betye Saar and David Hammons, to examine Black material culture. He’s also focused on creating authentic representations of Blackness in the absence of the Black body; imbued with a spirit of resistance, his artistic practice gives form to the formless.

All of these concepts are explored in Robillard’s debut solo exhibition, “Afrospirituality: Something Like a Phenomena,” on view through May 27th at Hausen gallery in Bushwick, Brooklyn. In “Afrospirituality,” Robillard enacts an intimate self-excavation grounded in his identity as a Haitian-American artist. Curated by the gallery’s founder, Usen Esiet, the exhibition draws heavily on West and Central African customs and traditions—most notably Kongo and Yoruba, which are both known for their strong ties to Haitian culture. “Afrospirituality” also builds on lines of inquiry posed in Robillard’s 2021 MFA thesis show, “Soliloquy: Hidden Acts of Resistance in the Plight of Black Visibility,” and his residency at Jank Museum, organized by the Center for Afrofuturist Studies.

If Sun Ra Gave Me The Keys To His Spaceship, 2022. Incense, wood, enamel house paint, pantyhose, staples, cowrie shells. 37 x 37.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Upon entering the space in Brooklyn, I’m met with an installation called From Slave Ships to Spaceships, which features a poem written by the artist himself named My Myths, and a dazzling mixed-media assemblage titled If Sun Ra Gave Me The Keys To His Spaceship. I sit on a low wooden stool to read the rhythmic text, eventually shifting my gaze upward toward the sculpture that looks like a hybrid of a spaceship and a dreamcatcher.

Placement Painting V: Soul(Ed) Across the Black Atlantic (With My Hues), 2022. Enamel house paint, African night soap, U.S. currency and stocking on canvas, 48 x 72 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Placement Painting V: Soul(Ed) Across the Black Atlantic (With My Hues), Robillard’s largest painting to date, prominently features a complex network of layered sneaker marks from the sole of Nike Air Force Ones in symbolic hues of blue, black, and brown. Robillard explains that the shades of brown represent the range of complexions on slave ships journeying across the Atlantic—while the blending of blues and blacks refers to the Black psyche, as described in Louis Armstrong’s song “(What Did I Do To Be So) Black & Blue?” The title of the painting also references W.E.B. Du Bois’s seminal work, “The Souls of Black Folk.” Sections of the painting are etched with thick coats of African night soap, creating a heavily textured finish and nodding to Robillard’s exploration into healing and purifying.

A Prayer’s Shadow, 2022. Window, incense, nails, Holy Bible, charcoal and oil stick on drawing paper. 30 x 38 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Across from the large-scale painting lives a powerful work titled A Prayer’s Shadow, which Robillard says is his favorite in the show. Within the frame of a white wooden window, an abstracted figure drawn from incense, charcoal, and oil stick features prominently; a copy of the Bible rests ominously in the bottom right corner. The ghostly figure appears to be clinging to the Bible, calling to mind the complex relationship between African diasporic communities and Christianity.

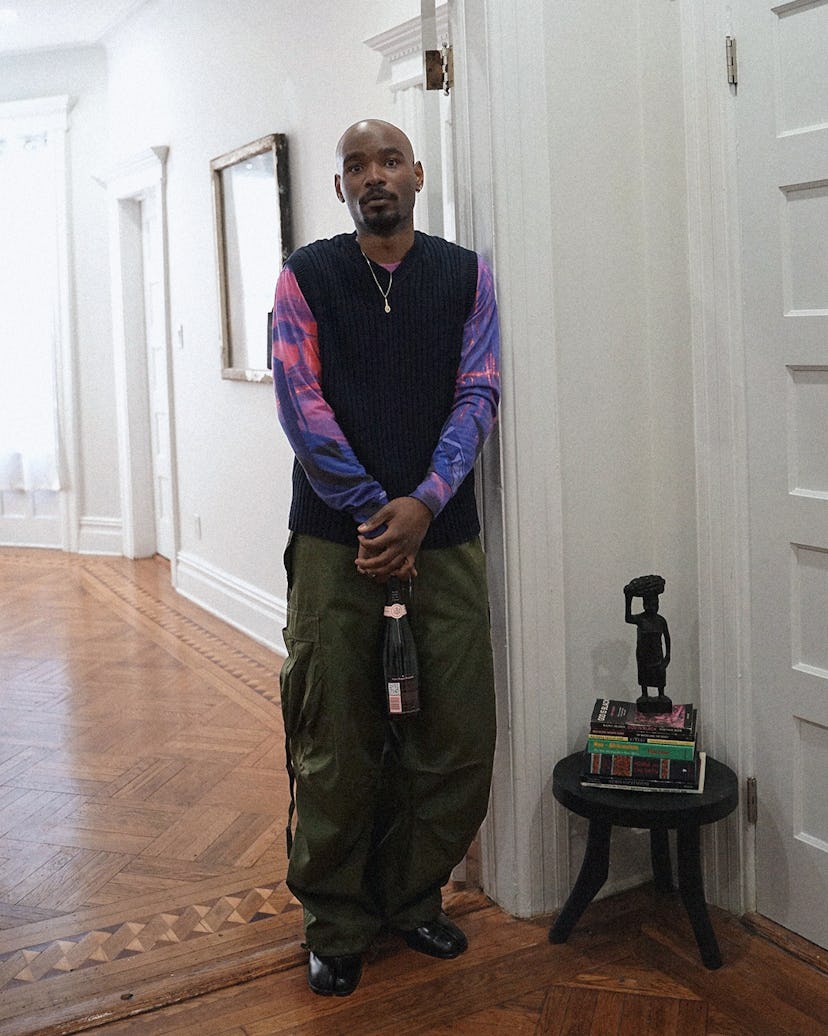

The final centerpiece is a black and white monochrome print titled, The Bull’s Horns (Papa Legba), which shows a self-portrait of the artist. In the work, Robillard frames himself as Papa Legba, a spirit in Haitian and West African religion who is described as a trickster, as well as the gatekeeper between natural and supernatural realms. The artist says his embodiment of the character is a reflection of his resistance to the art system.

The photograph also exists within a larger series titled, “Shadow Boxing” in which Robillard mulls sparring with his shadow self. Possessing an almost sculptural quality in its composition, the work stands out as the only photo in the exhibition, marking a shift for an artist who is typically recognized for his photography.

The Bull’s Horns (Papa Legba), 2022. Monochrome print. 35.5 x 47 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Perhaps most importantly, the photograph exists as a resounding expression of self-assertion from Robillard. “I think about [this photo] as a representation of a power figure,” curator Esiet says. “Lamar is talking about African spirituality, reclaiming our own sense of self, recognizing and celebrating our indigenous identity. This is part of stepping into that power.”