The ‘It’ Girl Is Dead. Long Live the People’s Princess.

A new cohort of down-to-earth and lovable stars is bringing realness to the cult of celebrity.

A term has been going around among the chronically online and celebrity-obsessed: the People’s Princess. A People’s Princess isn’t quite an “It” girl. There’s something more normal, everyday, and attainable about a People’s Princess. She is among her fans, not above them. She may even be in on the joke when it comes to the cult of celebrity.

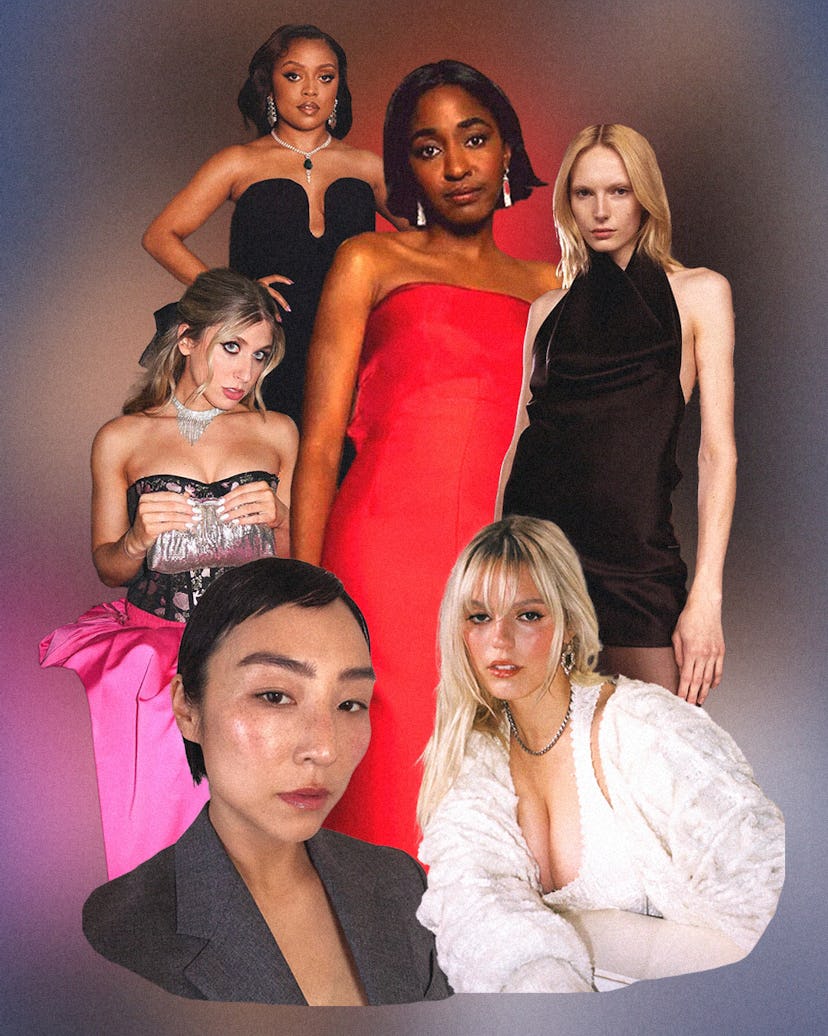

Among those crowned with the term include Quinta Brunson, Alex Consani, Greta Lee, and Reneé Rapp. But the undisputed queen of People’s Princesses—besides Princess Diana herself, who was originally given the nickname in the ’90s by her fans—is Ayo Edebiri. Throughout her awards streak—she won Best Supporting Actress at the Golden Globes, the Critics Choice Awards, the Emmys, and the SAG Awards for her performance in The Bear—the 28-year-old Boston native has captivated fans with a grounded, honest, and lovable vibe.

As the People’s Princess, Edebiri remains the picture of unproblematic, even when she gaffes. Case in point: After footage of her smiting Jennifer Lopez’s musical abilities surfaced days before she was due to host Saturday Night Live, with J.Lo as the performer, the singer later clarified that Edebiri apologized tearfully in her dressing room prior to hitting the stage. It was a situation that could have devolved into the stuff of diva-feud legend. But instead, Edebiri’s reputation remained intact because she handled a tricky situation as any normal person would.

According to cultural critic Evan Ross Katz, fans are drawn to stars with People’s Princess energy because of “a combination of regard for their work *and*—this is the part that makes it ‘people’s’—reverence for their ability to have not shed the exoskeleton of humanness that some celebrities do on their ascent to fame,” he says. Think of Jennifer Lawrence back in 2013, whose fall on her way to the Oscars stage cemented her status as a lovable star. Instead of a perfectly choreographed moment, we got a glimpse of real life.

But this new cohort takes the realness a few steps further. People’s Princesses often showcase a reluctance to, or detachment from, fame—combined with a clear-eyed understanding of how being famous affects mental health and the ways Hollywood can be a detrimental and damaging industry. And although she is famous and presumably booked and busy, she faces the same financial realities as the rest of us. During a year of Hollywood strikes and an economic downturn, this feels especially poignant. In Los Angeles, average rent costs nearly 60 percent of the average monthly earnings of a U.S. adult, and in the United States generally, grocery prices are higher than they’ve been in the past four years, according to the Washington Post. No one has been untouched, including the People’s Princess. Edebiri’s sound bites from her media tour promoting projects like The Bear, Bottoms, Theater Camp, and The Sweet East reveal her everyday struggles: she still rents her home and only recently got healthcare coverage. In an interview during the Emmy Awards red carpet, she revealed that as a child, she didn’t dream of accolades, but rather of the more workaday goal of having dental insurance. A People’s Princess has no qualms about discussing less-than-glamorous topics during TV’s most glamorous night.

But Edebiri is not the only person who has used her platform to reflect on America’s shortcomings. So how is a People’s Princess any different from an “It” girl, or perhaps those celebrities fans have dubbed “Mother”? Just ask writer Hunter Harris. “There is no higher designation than ‘mother’ and it implies a certain status and longevity—see: Julia Mother Roberts—and also knowing you have children to feed,” she says. “An ‘It’ girl strikes me as very downtown, a little aloof and offbeat. There is something surprising about an ‘It’ girl. People have only a broad, fuzzy idea of where they know you from. Parker Posey or Chloë Sevigny are the ultimate examples: I know them from Party Girl and Last Days of Disco, respectively, but I know them just as much from that New York Magazine cover and that Target photo call that goes viral once a year.”

Harris describes a People’s Princess as “someone who has graduated from being a regular person with regular problems to, like, a glamorous person with glamorous problems.” Of course, that trajectory is nothing new. So why create a term to differentiate it today? “I wonder if it has something to do with the nepo babies (both talented and not) and plants infiltrating every industry,” Harris says. “You have to put in work to be a People’s Princess; they don’t just appear out of nowhere.” Indeed, the recent cultural fascination with the spawn of celebrities and rich people means that seeing someone make the ascent to stardom from nothing feels significant in a way that it didn’t used to be. Maybe the People’s Princesses are so fun to root for not just because they are relatable, but also because the mere fact that their behavior is refreshing pokes a hole in the narrative that Hollywood is a meritocratic institution.

Social media has its fair share of People’s Princesses, mostly because relatability is one of the key tenets of being a successful creator. Sabrina Brier, a 29-year-old comedian who has found massive fame on TikTok and Instagram for her character videos that feature bits like “the girl who bullied you in high school and is trying to be an influencer” and “that friend who is embarrassed to have rich parents,” is often referred to as a People’s Princess by her fans.

“I hope part of why I’m sometimes called that has to do with the fact that I am speaking directly to ~the people~ in my content,” she says. “But hopefully also because they think I am a literal princess. Like in a big puffy dress.” In her eyes, the term is experiencing a resurgence because “people are less interested in celebrating exclusivity—as in, actual princesses and monarchies—and want to cheer on the everywoman.”

Perhaps People’s Princess just works because the term “It” girl is starting to feel dated. For Brier, the People’s Princess is “someone who is successful and powerful, but always remembers their roots, and slays in the service of others. The People’s Princess never pretends to not be a person. She embraces vulnerability.” And much like Princess Diana, who was the first People’s Princess, she interacts with the people who love her in a genuine way. And she isn’t afraid to express her gratitude for them.

But playing to your audience can be a tricky balancing act, especially in our social media age. What happens if a People’s Princess’s problems become less relatable? Does she lose her power, or simply graduate to Mother status? Only time and fickle Internet fandoms will tell. But for her part, Brier is the first to admit that she would not be where she is today without her audience. “They can call me whatever they want,” she says. “I would be honored to be the People’s Kitchen Wench.”

This article was originally published on