In People of the Mud, Luis Alberto Rodriguez Examines the Tenderness of Sport

The former dancer-turned-photographer traveled to Ireland to shoot hyper-masculine hurlers, who exhibited moments of vulnerability on the field.

As I continue to distance myself from friends and colleagues, I’ve found myself looking through Luis Alberto Rodriguez’s new book, People of the Mud. Having only started photography five years ago, and after fourteen years of working as a dancer, Rodriguez’s foray into the world of picture-making is unconventional, but has been monumental nonetheless. His first book illustrates the complex relationship shared by a team of hurlers—players of a sport native to Ireland—revealing their closeness, despite society’s rules of masculinity. What’s at the core of Rodriguez’s book, though, is an appreciation for Irish heritage and its ability to foster community and support, something that’s felt much more pressing right now, while the world is under quarantine. Read our conversation below.

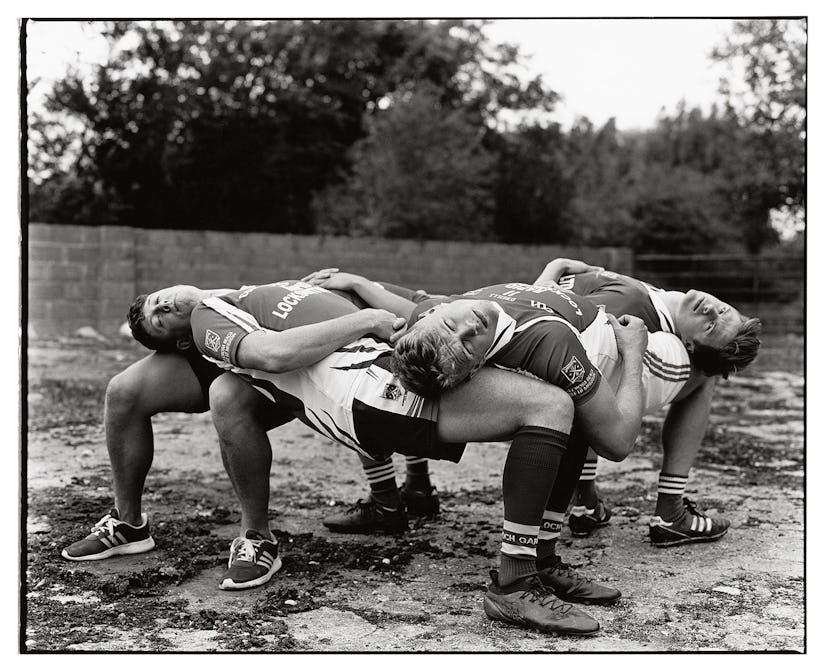

One of the first pictures I saw of yours was on Instagram. It was of these three men in sportswear—they were all stacked on top of one another, in this sort of fetal position pose. It struck me right away. When I found out you were releasing a book, I was so excited to speak to you.

Thank you. I just made this funny post on my Instagram because unfortunately, the book launched at the worst time ever [laughs]. I had a launch in London, and the next day, the coronavirus hit. So everything has been a little bit anticlimactic, because I had a launch in Ireland after that, which I was really looking forward to. After you’ve put so much work into something that, is your personal work and you’re so excited, then you get hit by this mess that’s happening right now. It’s just like, oh my god, are you serious?

At the same time, though, it’s a great time to be looking at work on our computers, and going through people’s archives. When did you start taking pictures?

I grew up in New York City and went to Juilliard for college. From there, I moved to Europe and worked professionally as a dancer for 14 years. When you are working in dance at such an intense, high level, your life is just consumed by it, which I’m very grateful for, but I didn’t have a formal arts education in photography. I started taking pictures seriously after I stopped dancing.

And this is your first book.

Yes!

A look inside Luis Alberto Rodriguez’s new book, People of The Mud. Photograph courtesy of Loose Joints.

How did you decide what your first book, People of the Mud, would be about?

I actually didn’t even know it would be a book at first. In 2017 I was one of the finalists at the Hyères festival, a competition of photography and fashion in the South of France, and I ended up being one of the winners of The American Vintage Prize, which allows you to have an exhibition at the festival the following year. So in 2018, there was this new program at the festival called Futures, where they pick six photographers for residency programs in partnership with France, Poland, and Ireland, and send two photographers to each country. I was nominated and ultimately selected for the residency in Ireland where I had to make work surrounding Irish Culture Heritage. The book is called People of the Mud because the town I was in, Wexford, was founded by Vikings. Mud is just earth and water and it’s always changing shape depending on who is leaving an imprint on the land.

How did you find these subjects?

At first, I was thinking about what I’d want to shoot. I was interested in physicality, and I had done this one picture before of two brothers hugging in the Dominican Republic, where my family is from. They sort of looked like they were in a knot, or it almost sort of looked like wrestling. So I was like, What if I referenced my own work for this, instead of basing this off someone else’s work? So then I was speaking to a friend of mine, and then he introduced me to his friend, in London, and she was from Wexford, the town I’d be staying in while I was in Ireland. So I started getting to know her and she was like “I’m going to be honest with you, in Ireland, people are not really comfortable with touching like that.”

I wanted to photograph a large family and create a very classical family portrait, but have them physicalize, so it’s almost like a big wrestling match. But soon I came to realize that was not going to be the reality of it—where the hell was I going to find a family that was willing to do that, especially how I wanted it? So then my friend suggested I look into hurling.

What’s hurling?

Hurling is this big national sport in Ireland, and the whole family is involved—it’s almost a religion, really. It’s a big deal. Sometimes there are five brothers involved, and people grow up and they stay on the same teams from childhood. Everybody’s cheering them on—the grandmother’s involved, the father, the sisters, everybody. So my friend introduced me to her brother, who is one of the main guys on this team, from the city where I was staying, and she suggested I try and work with them. I started watching hurling on YouTube and seconds into the game, the players are pushing and shoving, lifting each other up off the ground, and there’s this real sense of intimacy in all this. So I became really interested in their relationships as teammates and the relationship of the team.

Photograph from Luis Alberto Rodriguez’s new book, People of The Mud. Photograph courtesy of Loose Joints.

How did you get the team to agree to work with you?

I gave my proposal to my friend’s brother, and then he suggested I go to their locker room and pitch the team my idea. I went to watch one of their games and at the end of the match, I was so fucking scared, I went to their locker room and I told them what I wanted, what I was there to do, that I wanted to photograph the game, and learn from them—that I had no interest in making them uncomfortable, or having them do things that they were not accustomed to. So it was about taking what they were already doing, and shifting it a bit, and taking the time to learn from them about the history of the sport. I asked if any of them would volunteer to be a part of the project, and every weekend I’d go to meet with a core group of them and we’d make pictures. From there, I met more players and their friends.

I was actually going to mention that you can tell, when you’re flipping through the series, that your subjects look like they’re excited to collaborate; none of them look unhappy to be posing for you or like they didn’t want to be involved. I wasn’t familiar with this sport and from the photographs alone, I wasn’t able to identify it. I was struck by the camaraderie, but also small undertones of homoeroticism in the pictures. At the same time, though, nothing about these pictures are really that sexual, we’re just not used to seeing men touch one another in a platonic way.

It’s interesting, because what I learned is these guys have been on the same hurling team since they were children, and they’re playing for their parish. They’re actually not allowed to play for another team, ever. They’re comfortable and intimate with each other, but I don’t think they’re very aware of this intimacy, since they’re almost like family, having grown up together. I’d watch their games and drills and I would extract things that would work in a photo setting, but I basically just wanted to capture their closeness, and visually discuss the relationship formed among them.

A look inside Luis Alberto Rodriguez’s new book, People of The Mud. Photograph courtesy of Loose Joints.

This project makes me think about how in a lot of places, especially in the western world, any physical contact between men is sexualized, seen as gay, and then frowned upon. Despite participating in a lot of sports as a kid, I always resented this idea that athleticism was an expectation for boys. Sports, in the context of your project, though, becomes this arena for men to show affection for one another—to touch and form this intimacy that speaks to their friendships and how much they care for one another. In the eyes of everyone else, though, they’re just seen as athletes, so they’re protected from any judgement. When you think about it like that, sports are actually this really subversive thing pushing us forward.

For me, it’s all about the community and relationships that are in these pictures. I kept thinking about how seriously committed to the team these players were, from a young age, and how they’re never allowed to join another team for as long as they play the sport.

After shooting this project, what would you say about the value of sports in society?

It’s an opportunity to come together. It’s the opportunity to use the physicality of whatever sport you’re playing to form relationships and to have a community and support, which, I think, elevate the human spirit. You’re working toward a common goal and I think you can take that and apply it to whatever field you’re working in.

Would you say this project taught you anything about the importance of human connection?

Totally. I am a brown guy, going into a very white world in the south of Ireland on a farm. I came into this community, and people were so incredibly warm with me, and welcomed me with open arms. Of course, I had in mind, what I was trying to achieve, but I would always say, “What else do you guys do? Show me.” Because I don’t want to go there and just project ideas onto them.

Photograph from Luis Alberto Rodriguez’s new book, People of The Mud. Photograph courtesy of Loose Joints.

Were there any shots that were particularly difficult to achieve?

There were things that were more challenging, like that photograph of the players stacked on top of one another. The inspiration from that came from watching the games. When one player would miss a goal, he’d slam his body on the floor, to express, “Oh fuck,” and his disappointment. So I thought, what if I take that posing and duplicate it, having them all do it? Like multiple failure, you know?

That concept of multiple failure ties in nicely to this idea of community—because when one player fails or is upset, the entire team empathizes and feels it too.

Exactly. At first, when I suggested they climb on top of one another, there was some hesitation, but then they were like, “Okay, let’s try this!” So that was really special. You really see them go from feeling awkward to, all of a sudden, wanting to make it happen. It’s fun.

How would you say your discipline or your artistry that you developed early on as a dancer has informed your journey into photography?

Any physical kind of art form takes a lot of work. I’m going to stand up for dancers and just say, truly, nobody can fuck with us. I don’t mean that in a sense of, like, I’m the best, at all, but what I’m saying is that we are so underappreciated. The amount of work and sacrifice that a dancer makes for the art form is like no other. The way dance allows you to relate to other people can’t be underestimated, within the context of photography especially. In regards to the work ethic, I personally came from a very low-income family, growing up in Washington Heights in Manhattan, without many resources. I never had anything to fall back on or anything to catch me. So dance, as cliché as it sounds, really was a saving grace for me. It instilled a lot of discipline in me. Growing up in New York City, and going to Juilliard, I’ve always been quite spoiled with the amount of artistry and performance I was surrounded by. The level of talent I have been lucky enough to experience. Once I discovered Richard Avedon’s American West book, that was when photography became something serious for me. I knew I wasn’t going to half-ass this.

What are you most proud of at this point in your career?

The photography world uses this phrase “emerging photographer,” and so often someone who is “emerging,” is like, 24 or 25 years old. I’ve been photographing for five years—and it’s been a really good ride so far. I’m 39 years old, and I’m coming to this with a different set of tools. A lot of people don’t know I was a dancer. They don’t know that I literally had a whole other career before this. I’ve been fired, hired, and broke. I’ve been homeless.

People don’t know any of that. Where I am now took a lot of work. I’m so proud that despite everything, I just kept going.

People of the Mud by Luis Alberto Rodriguez, published by Loose Joints.

Related: Molly Matalon on Masculinity, Female Desire, and Her New Book