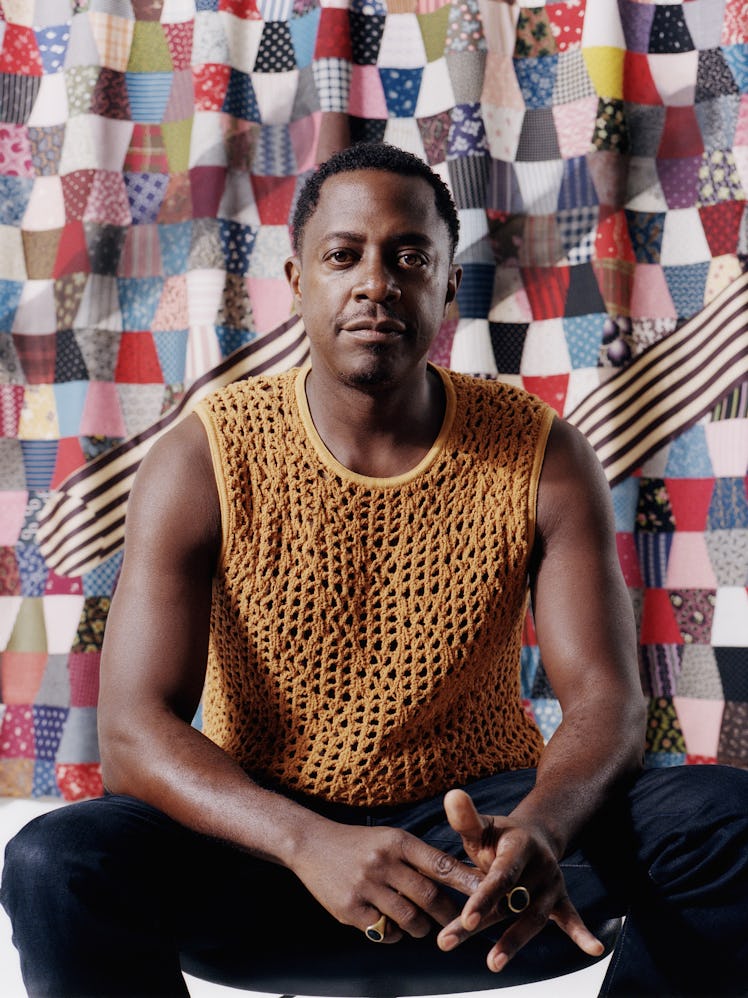

In a New Exhibition, Sanford Biggers Lives With “The Ruins of History”

The artist opens up his sprawling New York City studio to discuss a brand-new show at Monique Meloche Gallery in Chicago.

When I visit Sanford Biggers at his Bronx studio on a recent morning, the foyer resembles a gallery, with enormous quilts mounted on the white walls, tiny sculptures stationed on pillars, and a handful of employees typing away at their computers. Beyond the entryway, a whole team buzzes around, readying for the day; a large 3-D printing machine whirrs in its own room. Biggers—an artist whose mediums span video, music, performance, installation, photography, and more—runs around scooping up scraps of fabric, folding them, and arranging them in plastic tubs.

Biggers calls the fabric bits and paper cutouts taped up all over the room “rough drafts”—evidence of ideas he’s been playing with that weren’t quite developed enough when it came time to put together Back to the Stars, his show at Monique Meloche Gallery in Chicago, opening September 14. It is one of several projects coming to fruition this fall; Biggers also has an exhibition at Marianne Boesky, in New York, called Meet Me on the Equinox, up through October 14; and he’s unveiling two marble sculptures at the Newark Museum of Art in New Jersey on October 20.

The central idea behind Biggers’s fourth solo presentation at Monique Meloche was experimentation. “We wanted to do a show that had more of an installation feeling as opposed to lots and lots of objects,” Biggers explains. “Instead of saying, here’s the location and I’m going to tailor-make everything for the site specifically, it was more like, ‘Let’s make the work and then figure out how to best utilize the space.’ I wanted to have that freedom. Just play!”

Sanford Biggers, Promiscuous Platform, 2023

Biggers worked in two mediums that have long been part of his practice: quilts steeped in history, and marble sculptures that blend classically Eurocentric figures with African imagery. This time, though, the quilts take on a three-dimensional quality, while the sculptures—which are usually full figures—focus on a specific feature: a hand, a mask, or a bodice. Biggers cites his year-long stint in Italy at the American Academy in Rome during 2017 as a direct source of inspiration. “My apartment there was above a library, and I got to thinking about living on top of history, living with the ruins of history, the relics of history, the fragmentations of history,” he says. “Essentially, we’re all doing that all the time, but we rarely think about it.”

Biggers sources his quilts from all over the place; dealers and antique specialists will often bring a piece to his attention. “And then there are the random times when someone shows up with a bag of fragments or quilt squares,” Biggers says. “I was speaking in North Carolina once, and a woman drove 90 minutes to gift me a bunch of quilts from her neighbor.” The ones that will be featured in Back to the Stars show the artist’s efforts to “blur the line between soft and hard, organic and inorganic, sculptural versus graphic,” he says, “putting them all together so that they become a little bit more alien.” In a piece titled “Furrow,” for example, the fabric has been manipulated into wavelike ripples. “Sometimes, when I hit a mental block, I’ll put up some quilts on the wall and just sit there to be among them for a while,” Biggers says. “There is a textural, material, physical feeling. But there’s also the aura, the history, the other hands that have touched them, the other hands that have woven and sewn on them, and all of that is palpable to me. I really rely on those sources, that energy, to push me through to the completion of an idea.”

Sanford Biggers, Furrow, 2023

As a child, Biggers, a Los Angeles native, had to work overtime to keep up with the conversations that were happening at the family dinner table. “My dad was a brain surgeon and a Renaissance guy,” Biggers says. “To him, the brain was the universe. He took great excitement from everything the brain could do—our infinite potential—as well as our myopia.” Biggers’s sister, eight years his senior, was “very academic,” his brother was nine years older than him, and his mother was a teacher. “I ended up learning significant amounts of history that they were going through at the time just to be part of the dialogue,” he recalls. When he began studying art in the late 1980s at Morehouse College, Biggers became obsessed with the historical periods when artworks were made. What was happening around those artists at the time and, conversely, how did their work inform society? “It was very difficult being a student with that mindset,” Biggers recalls. “But it was natural to me. I had professors say, you have to decide the thing you want to do. But I was like, that seems antithetical to what I’m trying to do.” Biggers was still focused on the weight of history when his collaborative work with fellow artist David Ellis, “Mandala of the B-Bodhisattva II” gained critical attention in 2001 and launched his career.

Since then, Biggers has become known as an artist who cannot be pinned down. His pieces—which have been shown at the Tate Modern in London and at The Whitney Biennale—might reference African spirituality, Buddhism, Pop Art, Afrofuturism, hip-hop, or his personal experience as a Black man living in America. (He has been a central figure in the Black Lives Matter movement.) “Once you start to name and categorize things, you limit them,” Biggers says. “Those labels, those decisions, confine the work. I think artists have to always subvert that. That’s our job.”

Sanford Biggers, detail from Voyage to Atlantis, 2023

The artist’s diverse range of interests are translated in the works hung up all over his studio. He points to a trio of figures cut out of black cardboard covered in silver sparkles that’s been tacked up on the wall—another “rough draft.” The inspiration? His favorite comedian of the moment, Eric André. “He’s got that irreverence, that sort of punk, oddball, almost surreal approach,” he says. “It makes me think of [artist Steve] Kaufman: is it performance art? I can’t pinpoint it.” Ultimately, that ambiguity might just be the point. “I know it’s got to be hard to make a career that way, but we’re at a time where there is a place for that,” he says. “We need that fresh kind of energy.”