Queer Punk Icon Sean DeLear’s Teenage Diary Becomes a Memoir

I Could Not Believe It also includes remembrances from Rick Owens, Telfar Clemens, Honey Dijon, and Shayne Oliver.

The first time Michael Bullock met Sean DeLear at a house party in 2007, they immediately headed to the bathroom together, arm-in-arm.

“It was all the things: sex, drugs, instant bonding,” Bullock, a writer and editor, says from his home in Brooklyn. “There was an immediate camaraderie. He had a very different sense of freedom.”

Ask any of the friends, chosen family, creative collaborators, and folks for whom Sean DeLear was an artistic muse, and they’ll tell you about the way he lived his life: unapologetically, with no holding back. One of the pioneer members of the “Silver Lake scene” of post-punk and power pop in 1980s and 1990s Los Angeles, DeLear was the lead singer of the band Glue, and a notorious “It” Girl who seamlessly weaved between scenes, transcending barriers associated with sexuality, race, and gender decades before it was commonplace to do so. DeLear was a fixture on the New York City and L.A. party circuit, and knew absolutely everybody who was anybody. (According to DeLear’s L.A. Weekly obituary published in 2017, the B-52s were fans of DeLear’s, not the other way around—and “Posh Spice and Yoko Ono were kissing his ass.”)

When DeLear passed away that year after a short fight against liver cancer, he was living in Vienna, Austria. Cesar Padilla, a longtime friend and writer-slash-musician-slash-fashion-archivist, offered to help with the funeral arrangements. While clearing out DeLear’s belongings, Padilla stumbled upon a diary written by DeLear in 1979, when he was 14 years old. The journal, in which DeLear wrote daily, was a treasure trove of thoughts and emotions, straight from the mind of a queer, Black teenager growing up in the Simi Valley of California—a notoriously conservative area outside of L.A.—with Christian Fundamentalist parents. But it was also something of a time capsule, capturing the pop culture landscape in California during the pre-AIDS era.

Sean DeLear in 1987 at the Hollywood sign.

“It was an amazing coming-of-age story that gays hadn’t read because it was an authentic voice,” Padilla, speaking over Zoom with Bullock, says. “It wasn’t looking back on your life, or it wasn’t a fictional narrative. It was honest as can be. No shame, just living a true life. And funny as shit.”

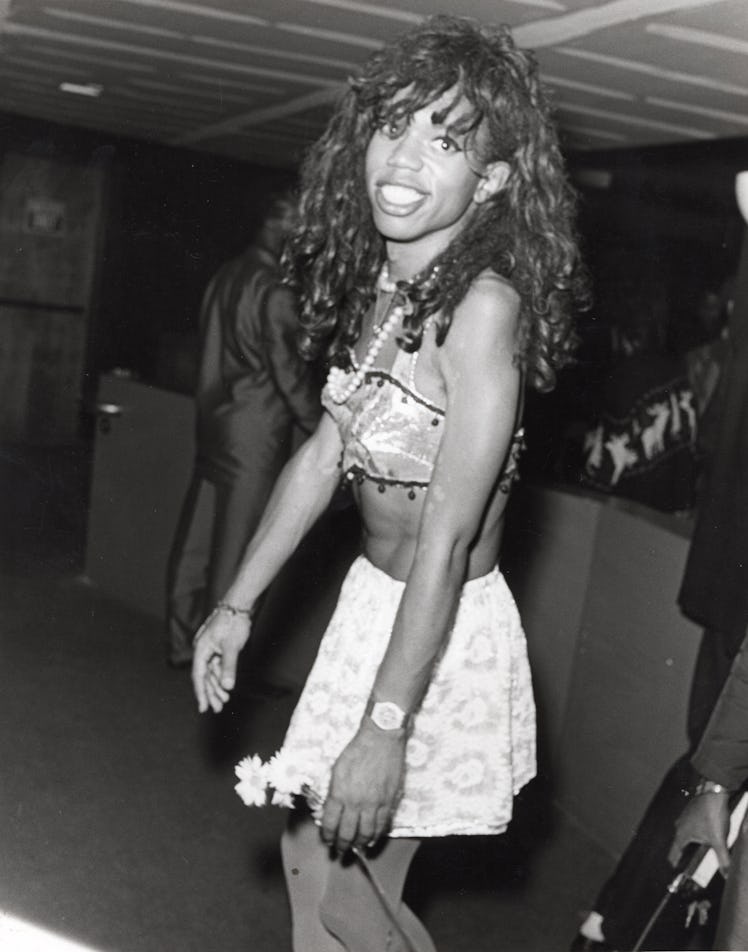

Sean DeLear in 1986.

Together, Padilla and Bullock have turned the diary into a book, titled I Could Not Believe It, published by Semiotext(e). Along with DeLear’s entries, the slim volume contains a foreword by author Brontez Purnell and accounts from Rick Owens, Telfar Clemens, Shayne Oliver and many more creators who were friends of DeLear’s—and who were directly influenced by him.

Sean DeLear in 1981.

But it’s DeLear’s own words that are the most absorbing, bringing you directly into his world of adventure. In his frank and direct tone, the teen describes his myriad crushes and hook-ups; hustling for money; his love for Donna Summer, his new waterbed, and bowling; racist encounters, and many afternoons spent at glory holes, in bushes, and inside bathroom stalls with older men.

Sean DeLear in 1987.

“Up until that point, gay coming-of-age narratives were about: ‘How do I tell people?’ and getting over this deep shame,” Bullock says. “That that wasn’t part of his trajectory was an incredible thing to me. And I thought that could be a very useful idea to a lot of other people dealing with sexuality: not accepting that shame.”

DeLear in 1987.

“I’d read The City and the Pillar, I’d read A Boy’s Own Story, which was the big coming-out book that Edmund White wrote in 1979,” Padilla adds. “This text of Sean’s was written the same exact year, and it’s been hidden. But this is what every one of those writers wanted to say, and they couldn’t.”

The language of DeLear’s diary is certainly up-front: “I always seem to have a hard-on, I cannot believe it,” he writes in one entry; “Nothing happened today. I went to the swap meet to meet a guy and get a trick but no luck as always,” he says in another. But in its frankness, it reads like a young Henry Miller or John Rechy. The book is also an indelible picture of the sexual revolution—a time lost once AIDS came around one year later in 1980.

Sean DeLear in 1986.

“With people blaming gay folks for AIDS and the psychology of sex and death being equal, basically, after that year, for gay men, sex and death were tied together forever,” Bullock says.

“We lived in a world of danger,” Padilla recalls. But DeLear’s existence surpassed those earthly dangers—and that was another large reason why the duo endeavored to publish his diaries. “She was just effortless, graceful,” Padilla adds of DeLear. “To see that kind of beauty walk through danger, through the different scenes, seamlessly and often within one evening, was something to behold.”

DeLear in 1982.