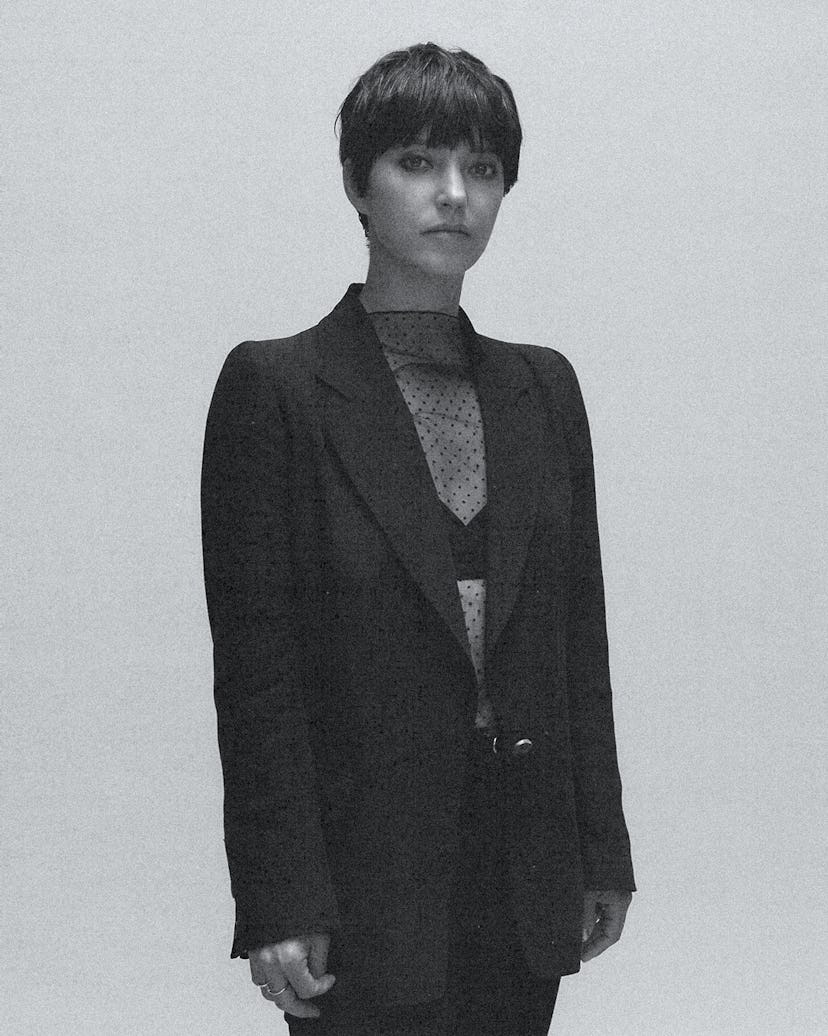

Sharon Van Etten Brings It All Home

By now, Sharon Van Etten can’t quite remember how many times she watched The Sandlot over the pandemic with her five-year-old son. But what she does remember is this: During one particular viewing in 2020, she came up with the title of her forthcoming sixth album, We’ve Been Going About This All Wrong.

For a while, she thought she’d call the record Good For You. She liked the play on words—like a kiss-off, but also like something positive, beneficial. She had a playlist by that name, filled with songs that she hoped to use as sonic references: some Cocteau Twins, Rowland S. Howard, a lot of English alternative rock. Then she had a minor epiphany while watching The Sandlot, during a scene when the kids attempt to retrieve a lost baseball from the neighbor’s yard and things go terribly, horribly awry. “We’ve been going about this all wrong,” one of the boys sighs.

“I laughed, and then I teared up at that sentiment,” Van Etten, 41, says over video chat. “You feel you get over these humps, and you feel you’re almost there, and then something happens.” It’s also an appropriate mantra for the past two years, when time passing was tracked as much by reports of rising and falling Covid case counts as by weeks or months. Before she started doing interviews this year, members of Van Etten’s publicity and management team asked her if she was going to “go there”—to refer to We’ve Been Going About This All Wrong as a product of the pandemic “If anyone says they’re not putting out a Covid record, they’re fucking lying to you,” she tells me.

Van Etten began writing We’ve Been Going About This All Wrong in 2020—aside from two songs, “Darkish” and “Far Away,” which she wrote earlier and then set aside because, at the time, she thought they were “too apocalyptic.” (I find this funny, I say, because her writing tends to be fairly dark. “Right? I mean, I put jokes in there. I temper it a little,” she says. “I have to have a joke in there somewhere, to remind people that I am a human being.”) The album does bear an apocalyptic imprint—near the end of “Darkish,” Van Etten asks, “Where will we be when our world is done?”—but it’s also a sort of reorientation around the idea of home. On “Darkness Fades” and “Headspace,” there’s a sense of estrangement from a partner; on “Come Back,” she grasps again for connection. On “Home to Me,” Van Etten addresses her son directly: “Don’t turn your back. Don’t leave,” she sings. “You’re on my mind, do you not see?”

Earlier this year, she put out two songs—“Porta” and “Used to It”—which emerged from the same writing period. But she released no singles from the album, which comes out this week. She wanted listeners to take it in from start to finish and assign their own meaning to songs. Like a hand outstretched, saying: This was my experience. Maybe it was yours, too.

If Van Etten’s previous album, 2019’s Remind Me Tomorrow, was about looking back on her life so far, We’ve Been Going About This All Wrong focuses on where she’s at now.

“I think there’s a fearlessness that’s really become front and center with her,” says Zachary Dawes, who plays bass on We’ve Been Going About This All Wrong and Remind Me Tomorrow. “She’s not scared to make it personal, and in her singing style, she’s not scared to scream and to really deliver.” (Dawes emailed me later and wrote that, after working on a couple of other projects with Van Etten, he “realized I wanted to work with her as much as I could, and I wasn’t afraid to let her know that.”)

Van Etten had lived in Brooklyn for nearly 15 years when, in September 2019, she moved to Los Angeles with her partner (the music manager, and her former drummer, Zeke Hutchins), and their son, then 2. She wanted “to try to slow down,” she says—to have more space for her family and to build a home studio from which she could write and record herself, and to work on more projects that wouldn’t require her to be on the road. She and Hutchins were supposed to get married in May 2020; in February, traveling to Mexico for her bachelorette party, she found that LAX was empty. “That was the first time I remember thinking, ‘Oh, this Covid thing might be something,” she says.

Then everything shut down. “Here we are in our new home, still unpacking, still figuring out, ‘Where are we? Who are our neighbors? What are we doing here?’” Van Etten says. She and Hutchins had to learn to navigate their jobs, her classes (she resumed work on her undergraduate psychology degree in 2020), their relationship, and parenting under the same roof, while trying not to let on to their son how scary the world around had become. It wasn’t only the pandemic; it was also the longer, increasingly ferocious fire seasons in California brought on by climate change; rising gun violence; protests over racial justice—all the ways that individual anxieties were exposed to be community ones, too. It comes through in the music. “I wanted to acknowledge what we were going through in our political climate,” she says, “and just be able to put into words my frustration and my anger.”

“Her art comes from her experience—like everyone’s art—but hers is in a very profound, honest way,” says the music supervisor Maggie Phillips, a close friend of Van Etten. “She is making this music because she is fully compelled to do this.”

Van Etten’s creative universe has expanded lately. Since 2019, she’s worked with Jeff Goldblum, Angel Olsen, and Big Red Machine. She has a forthcoming song with Margo Price. And that’s a partial list. She’s written and recorded songs for movies, and she made her film debut in Never Rarely Sometimes Always, Eliza Hittman’s understated drama about a teen seeking an abortion in New York, which premiered at Sundance before its release in March 2020. (Her song “Staring at a Mountain” appears at the end of the film, which Phillips music-supervised.)

Hittman was polishing her script when she began listening to Remind Me Tomorrow, not long after its release in early 2019. She met Van Etten at her apartment—still in Brooklyn then—to talk about the script, and the conversation quickly turned to “what a challenge it was to juggle our lives and career goals” as working mothers, Hittman wrote in an email. Later, on set, Van Etten was nervous. Hittman encouraged her to wordlessly channel a sense of maternal responsibility in her scenes. “Her performance transformed and became more grounded and personal,” Hittman wrote.

“A lot of my acting in that is quiet and internal,” Van Etten says. “It’s really about my presence.”

Part of the lure of Los Angeles was to collaborate more. Though isolating prevented doing so in person, Van Etten, Dawes, and other friends sent tracks back and forth; she says working with other artists at a remove helped her “not feel the pressure of being in a room with someone and creating something magical in that one session” and embrace her home studio. “I’m a Pisces, so I’m scattered and I have a lot of projects all the time,” she says. “Those types of deadlines are so good for me.”

She knew she wanted to mostly record We’ve Been Going About This All Wrong there, too—in her space, on her terms. She sent reams of files from different studio sessions to Beatriz Artola, her mixing engineer. Artola (who was pregnant while working on the album, adding resonance to songs like “Home to Me”) says that a collaborative ethos comes through in Van Etten’s solo work, too. “Oftentimes, many artists are like, ‘I’d love to hear you do your thing, I’m open to interpretation’—and more often than not, it’s like, ‘I like what you did, but no,’” she tells me. “When Sharon asks you for your opinion, she really means it.”

But as her career has taken off, Van Etten has grown more wary of having a public profile. After the release of Are We There in 2014, she “toured incessantly,” a recent Stereogum story describes. It was challenging. “It became too hard for me to go to the merch table,” she later writes in an email. “My voice wouldn't last and my stamina emotionally was at odds with the needs of the fans and the personal stories they would tell.” (This is also one of the things that inspired her to study psychology.) When we speak over Zoom, she’s visiting family; afterwards, through her publicist, she asks me not to include her location in this story.

“It’s starting to make me uncomfortable,” Van Etten says. “There’s a power of anonymity…” She pauses. “I have these concerns, being a mother and being in the public eye. I just want to sustain where I’m at without changing anything in my life.” It’s made her reluctant to pursue more acting (though she’s had recent auditions), and she’s “dreading” touring; for all the difficulties of the past two years, she says, having so much time to be present with her son was not one of them. “But it’s also nice to miss each other, too,” she says.

Before she embarks on tour, Van Etten has assigned herself a new project: repairing a pair of refrigerator-size Magnepan speakers she found at a thrift store. In or out of the studio, there’s always something to make next.