You’ve been the bouncer at Berghain, the world’s most famous techno club, since its very beginning. You were hired in 1998 at the club’s first iteration, Ostgut, located in a former freight railway station. When it was renamed and relocated to an old thermal power plant, you moved with it. Last year marked Berghain’s 20th anniversary, which was celebrated with a weekend-long party. How was that?

Sentimental and a little melancholy. It’s been a long time—nobody would have thought it at the opening. To have been part of it all for so long, to have stayed true to an idea—I am very proud of that.

Is it nostalgic?

No, I don’t think I’m a nostalgic person—not yet. [Laughs] I’m not one of those people who say, “Oh, things used to be so much better.” I thought, Let’s see what happens next.

To be a bouncer, is it necessary to have been part of the scene?

It’s not a bad basis.

Berghain is notoriously difficult to get into, with people waiting in line for hours just to be turned away with a terse “Sorry, not today.” There’s an active online community that discusses everything about Berghain, including hacks for how to get in. Do you pay attention to that at all?

I’ve only been active on social media for two years. Everything you’ve just described, I don’t deal with that. Zero.

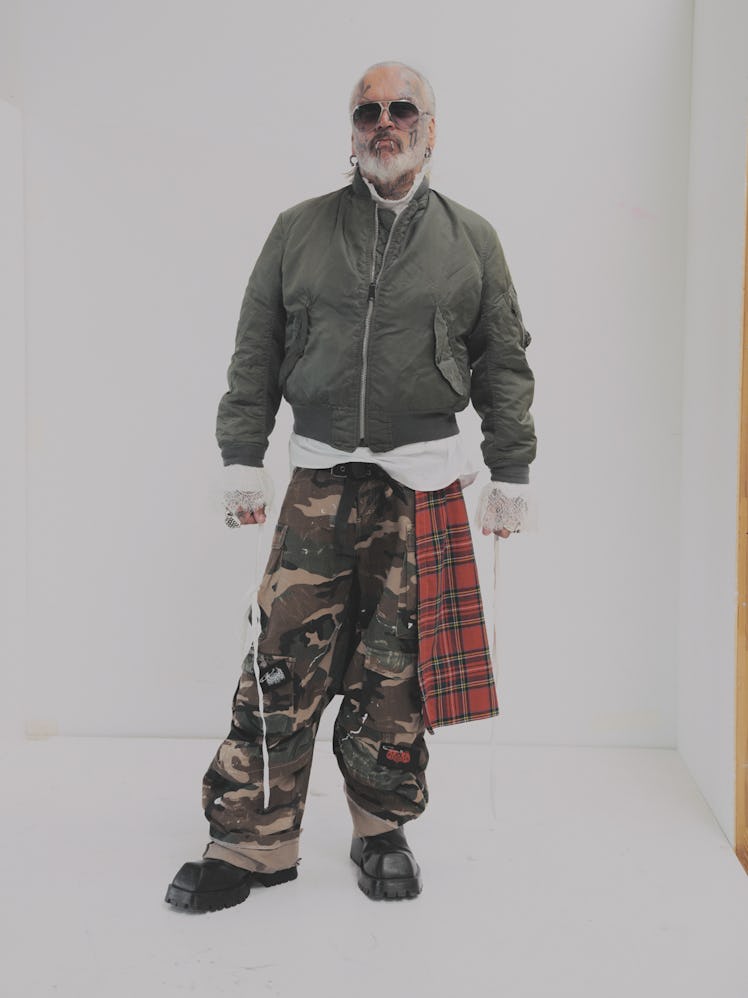

The types of people who get into Berghain have evolved over time. For example, clubgoers today dress less kinky, more sporty. To what extent have you steered this change? Or is the clientele more an expression of the zeitgeist?

I think the phrase “expression of the zeitgeist” is actually a very good one. So much has changed with the zeitgeist. There’s always a new, young audience, which is great for the club, because partying, music, and ecstasy should be sexy.

You were born in Germany the year after the Berlin Wall was erected, in the Soviet-controlled, eastern half of Berlin. What was it like coming of age under a communist regime?

It was a dictatorship. The freedom that we artists and dissenters needed was found in the club scene. Although the term didn’t exist yet, the scene represented a “safe space” for us.

After graduating from school, you became a punk and started photographing your peers. When the Soviet Union collapsed, you stopped taking photos. Eventually, you picked it back up, and now your signature black and white portraits are exhibited around the world. Why did you stop?

I once talked to a journalist about it. He asked me if I realized that with the fall of the Berlin Wall, in 1989, millions of East Germans suddenly had a migration in their own country. It meant the loss of their own identity. Everything was taken away from them, for many people in a material sense: apartments, houses, jobs. In my case, it meant that I put the camera away. I felt it was no longer important. In the ’90s, my time with the most parties, the most drugs, the most tattoos, I didn’t take any photos. At some point, Ostgut closed down and I suddenly had a lot of time. That’s when I started photographing again.

You could have devoted yourself entirely to photography, but you still enjoy working at the door.

I’m at Berghain less, but it’s still totally inspiring. I interact with a new generation that I wouldn’t otherwise have any connection with. I find it more inspiring than sitting in an office with 20 curators.

In your 2014 autobiography, The Night Is Life, you wrote that you used to end your shift at the door with a round on the dance floor, but that you no longer do that. You’re 63 now. Do you still feel part of the club scene?

I still belong to the scene, but I’m no longer the party generation. I’ve always liked the fact that the club is a mix of different generations. I think that’s very important—that the others, who are a bit older, feel comfortable.

Grooming by Anna Burdine. Producer: Joshua Kurths; Photo Assistant: Jakob Müller-Meernach.