In a Season of Fashion Upheaval, Designers Return to the T-Shirt

Draped in satin and dusted in jewels, the humble wardrobe staple goes from off-duty standby to red carpet contender.

Of the more than 20 designer turnovers that have roiled fashion in the past year and a half, perhaps the most anticipated was the debut of Matthieu Blazy at Chanel. The French-Belgian designer had steered Bottega Veneta, where he was previously employed, away from its established ethos of quiet good taste toward a more ebullient expressiveness, a precedent that hinted at major transformations to come. Any change at Chanel is meaningful, simply because no other French house has had such a lasting impact on what we wear. Coco Chanel wasn’t quite the one-woman revolution she claimed to be, but her radical simplicity and insistence on comfort foretold the future. Her most famous aphorism, “Elegance is refusal,” says it all.

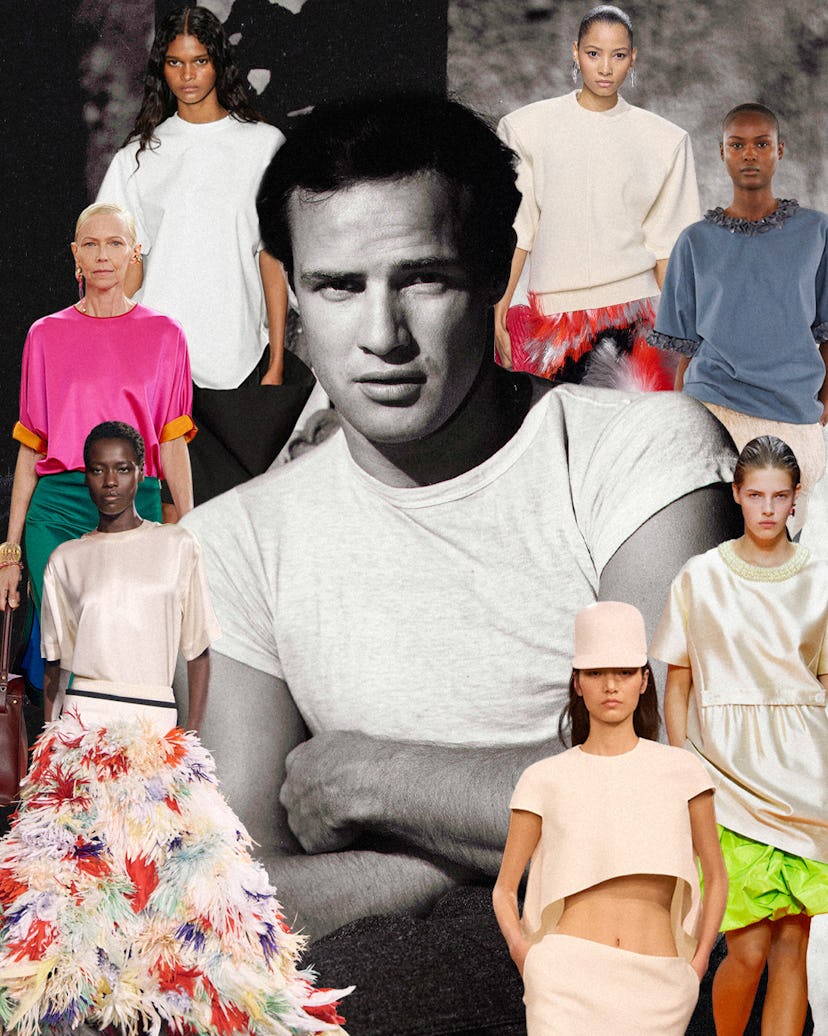

Blazy’s definition of elegance is embodied in his first collection’s final look: a feathery, multihued evening skirt topped with…a satin cream T-shirt. It’s a pairing that unites unabashed artistry with the utilitarianism of a garment that had its genesis in the men’s underwear department (a nod to Chanel herself, who appropriated wool jersey from the same source). Beautiful and easy, the combination so delighted model Awar Odhiang that she twirled in spontaneous glee as she completed her circuit on the runway.

If that had been the sole T-shirt on the spring catwalks, the story would end here. But, in fact, the tee is one of the season’s key silhouettes. At Fendi, a satiny pink version with casually rolled sleeves was tucked into a brilliant green skirt for a relaxed take on formality. At Diotima and at LII, the tees were slouchy and oversize, as worn on the streets of New York, where both brands are based. Louise Trotter, who took over from Blazy at Bottega Veneta, gave her tees structure via built-up shoulders. For his first Balenciaga collection, Pierpaolo Piccioli experimented with cropped styles. At Prada, tees got the off-kilter embellishments—such as jeweled collars and martingales—that are the brand’s signature.

In its straightforward way, the T-shirt wears its etymology on its sleeve, literally: It’s named for the shape made when it’s laid flat. This silhouette is so elemental that it predates the late Middle Ages (which was when capital-F fashion kicked off); before that period, the T-shaped robe was as exciting as things got. The actual T-shirt is much newer, a descendant of the flap-seated wool union suit of the 19th century, which was eventually separated into more comfortable top and bottom components. By the early 20th century, advances in knitting technology had made the crewneck possible. This innovation soon displaced the old button-up henley style, and was hailed in an ad by the Cooper Underwear Company (now Jockey International) as perfect for unmarried men, who couldn’t possibly be expected to replace their own lost buttons. Side-by-side photos showed a glum chap in a clumsily repaired henley, contrasted with a confident-looking alpha male, luxuriant handlebar mustache bristling, wearing the new crewneck style. But these “bachelor undershirts,” as they were called, had long sleeves.

The first truly modern tee dates to 1913, when the U.S. Navy adopted a snug, stretchy white cotton crewneck with short sleeves for its sailors. Seven years later, the T-shirt was an established part of the young male wardrobe, listed by F. Scott Fitzgerald as an item of clothing Amory Blaine packs for prep school in This Side of Paradise—one of its first appearances in print.

During World War II, millions of American men donned tees as part of their military uniforms. Images of them were seen back home via newsreels and magazines, and the soldiers continued wearing the style when they returned to civilian life. Still straddling the line between inner and outerwear, the postwar tee had rebellious, hypermasculine connotations. No one embodied this more vividly than Marlon Brando in the 1951 film A Streetcar Named Desire: As the loutish but swaggeringly erotic Stanley Kowalski, he wore his torso-hugging tees the way an animal inhabits its skin.

Although women have been sporting T-shirts since the 1930s, it was only after fashion relaxed in the 1960s that the garments took on wardrobe hero status, anchoring the looks of mood board stalwarts like Jane Birkin and Carolyn Bessette Kennedy. Less fussy than a blouse, more versatile than a shirt, the tee is the platonic ideal of a top, conferring effortless cool.

Despite countless “most wanted” lists claiming otherwise, there is, of course, no single perfect tee. But the staple’s wide availability, range of prices, and high-meets-low aesthetic are constants. The fashion industry, as noted, has been experiencing seismic shifts. In an ocean of uncertainty, the tee is a life—or at least a wardrobe—preserver.

Runway, clockwise from bottom left: Courtesy of Chanel; Courtesy of Fendi; Courtesy of LII; Courtesy of Bottega Veneta; Courtesy of Diotima; Courtesy of Prada; Courtesy of Balenciaga. Center: John Engstead/Warner Bros./Kobal/Shutterstock.