Row and Behold

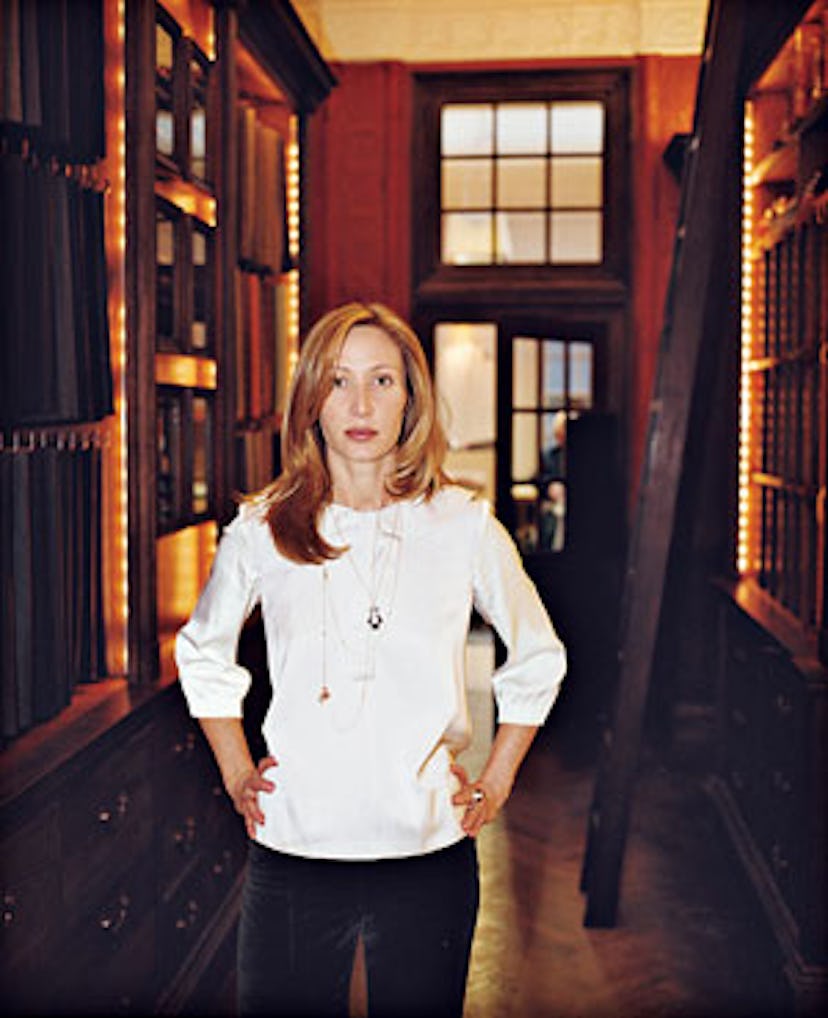

As the sole female on Savile Row, Anda Rowland is reinvigorating her father’s staid shop.

Savile Row is no place for little girls, as Anda Rowland discovered at age six. That’s when she paid her first visit there, accompanied by her father, the famously dapper multimillionaire Roland “Tiny” Rowland, who owned Anderson & Sheppard, the London tailor—and Row fixture—that has dressed customers from Fred Astaire and Duke Ellington to Bryan Ferry. Back then, the store was a stuffy stalwart with a Dickensian air: bolts of fabric piled high in the windows, cutters snipping away behind curtains and clerks perched on high stools, scribbling measurements and orders into fat leather-bound books. “It was always very scary,” says Rowland, 37. “Unless you were very self-confident—or a public school boy—you could feel that you weren’t really welcome.”

Those apprehensions are long gone. In 2004 Rowland quit her job at Parfums Christian Dior in Paris, moved home, and took over the day-to-day operations at Anderson & Sheppard, where Alexander McQueen first trained when he was 16 and where Ralph Lauren and Tom Ford have come, periodically, to observe John Hitchcock, the head cutter and managing director of the company, in action. Today Rowland is the only female principal on Savile Row, and she is transforming her family’s prestigious but fusty firm into a 21st-century luxury-goods operation. Before her arrival, the company was without a Web site or viable computer network; costs were left untracked; and 500,000 pounds, or about $1 million, worth of unpaid bills had piled up. “There was this sense of embarrassment about asking for payment—it’s very charming,” says the soft-spoken Rowland, who resembles Cate Blanchett, with her reddish-blond hair and fine features. “But that’s the beauty of coming in from the outside. You say, ‘Wait a minute, that 500,000 pounds could be spent on a shop refit!’”

The shop’s librarylike waiting room.

It is a dark, winter afternoon, and over tea and panettone in the tiny office that overlooks the cutting room, Rowland is discussing the advantages of her professional background. “At the top end of any big beauty company is business—in marketing, you’re looking endlessly at your costs,” she says. It also helps that her father never took an active role in running Anderson & Sheppard. “You don’t have the weight of history,” Rowland says. In fact, she doesn’t even feel duty-bound to dress in bespoke clothes. Today she’s wearing a tailored green velvet Chloé pantsuit—and khaki

Converse All Stars. “This really isn’t a look, is it? I did mean to change my shoes,” she says apologetically.

Anderson & Sheppard was founded in 1906 by the Swedish tailor Per Anderson; Rowland’s father purchased it in the late Seventies. He died in 1998, and the Rowland family still holds an 80 percent stake, with the remainder in the hands of the cutters and managers. Rowland, a graduate of the London School of Economics and Insead, the European business school in Fontainebleau, France, never planned to follow in her father’s footsteps. But after stints in marketing at Estée Lauder in London, and later as promotions and special events director for Parfums Christian Dior, she returned home partly out of a sense of obligation. In 2004 the lease ran out on Anderson & Sheppard’s 30 Savile Row space, the tailor’s home since the Twenties, and the landlords wanted to raise the rent. After Rowland’s mother, Josie, decided to relocate to the current, smaller premises on nearby Old Burlington Street, she appealed to her daughter for help. “It was a big wrench, but having said that, it was clearly a great opportunity—and a duty. This business had been going on for 98 years, and were we going to be the owners responsible for its demise?” she asks, noting that her three siblings didn’t have the background for this particular trade. Rowland’s brother, Toby, who is married to writer Plum Sykes, is an Internet entrepreneur, while her sisters Louisa and Plum work in TV production and theater, respectively.

Rowland, who is now vice chairman, refused to look back; even though the new store was technically off the Row—and just one third the size of the original one—she was determined to do the company proud. Rowland called in Jérôme Faillant-Dumas, whose Paris-based design agency L.O.V.E. works for such clients as Dior, Chaumet and Nina Ricci, to create the interior of the new location. The shop now resembles the library of an old Mayfair home: dark parquet floors, molded ceilings, sketches of hounds hanging on the walls and a marble fireplace, with, of course, a fire blazing on chilly days. Previously, the cutting room was off-limits to customers, but today they’re invited to watch the making of their soft, draped wares. (Cutters typically take 50 measurements for one suit, while each piece, shoulder pads included, is hand-cut.)

Rowland also spruced up the shop’s packaging, swapping the generic plastic sacks for dark brown paper ones and upgrading garment bags from synthetic to cotton twill. “There was a problem when I tried to get rid of [the sacks] because they were considered well designed and part of the charm to the old English boy,” she says with a laugh. But no luxury- goods firm can afford to be that understated—especially when its suits cost upwards of $5,500. “People today equate the quality of the product to the bag it’s given away in. They are small things, but they count.” The changes paid off: The firm, Rowland says, is now turning out its best profits in 15 years.

The archive book of fabric swatches

Those initiatives have all been noted by the Savile Row Bespoke Association, which aims to protect and promote British bespoke tailoring along the lines of the Chambre Syndicale de la Mode. (Rowland is the association’s only female board member.) The guild was formed in 2004 to promote education about bespoke tailoring and to help counter negative press reports predicting the Row’s demise. Angus Cundey, a fellow board member and chairman of Savile Row tailor Henry Poole & Co., says Rowland has completely transformed Anderson & Sheppard. “It used to be a rather reclusive company that didn’t talk to the press, belong to trade associations or take part in charity work,” he says. “But she’s put the company back where it should be. She gets things done.”

Rowland grew up with a clear appreciation of the well-dressed man. Her colorful—and often controversial—father was a businessman of Anglo-Dutch and German descent who made his fortune in African mining, later building a business conglomerate that included Britain’s Observer newspaper. The British satirical magazine Private Eye frequently referred to him as “tiny but perfect,” because of his dapper style. “My father was always beautifully dressed. He had a dressing room and a wonderful valet, while my mother probably had two cupboards,” recalls Rowland, who appears to have inherited her father’s love of dressing up.

“She’s the most elegant, eclectic person,” says Rowland’s good friend Carmen Busquets, the founder and owner of the Web-based luxury retailer CoutureLab. “She loves mixing vintage clothes with beautiful, modern jewelry, or modern clothes with vintage jewelry from her mother—but she never tries too hard.” Her own wardrobe may be packed with treasures, yet Rowland has already ruled out a move into women’s wear. “There is still plenty to do in the men’s arena,” she points out. “There are enough men who need to look better.”