Perfect Vision

One afternoon a few years ago, while Diane von Furstenberg was talking to designer Bill Katz about how to renovate the 19th-century Connecticut barn that had served as her beloved retreat for more than 25 years, Katz told her she should demolish the place. The building, one of five on von Furstenberg’s 100-acre farm, was beautiful, Katz acknowledged, but it was poorly laid out with no proper foundation, and rebuilding was the best option. Von Furstenberg looked pointedly at Katz (who’d previously designed four other spaces for her, including her New York home and studio) and asked, “Are you sure?” He was, and she agreed to move out of the barn so Katz could start over.

Katz’s name may be unknown to the general public, but for decades he has served as designer, architect and aesthetic consigliere to many of the world’s creative heavyweights—particularly A-list artists such as Anselm Kiefer, Cy Twombly and Jasper Johns. Although these aren’t generally the kind of people who seek out second opinions about how things should look, they all rely on Katz as their secret weapon. When Kiefer saw a run-down 17th-century hôtel particulier for sale in Paris’s Marais neighborhood, he flew Katz in from New York to help decide whether the space could be transformed into his new home and studio. Recently completed and already legendary in art-world circles, the compound now takes up 60,000 square feet of central Paris real estate, including three underground floors that stretch almost an entire city block.

Katz’s latest project, opening in late February, is the much-buzzed-about new European headquarters of auction house Phillips de Pury & Company, in an old mail-sorting depot on Howick Place in London. Over the years he has also worked on dozens of more personal projects, from installing Twombly’s exhibits to designing every detail of Johns’s Connecticut house—even the artist’s bed and kitchen countertops.

The raw space that Katz is turning into Phillips de Pury’s new European headquarters

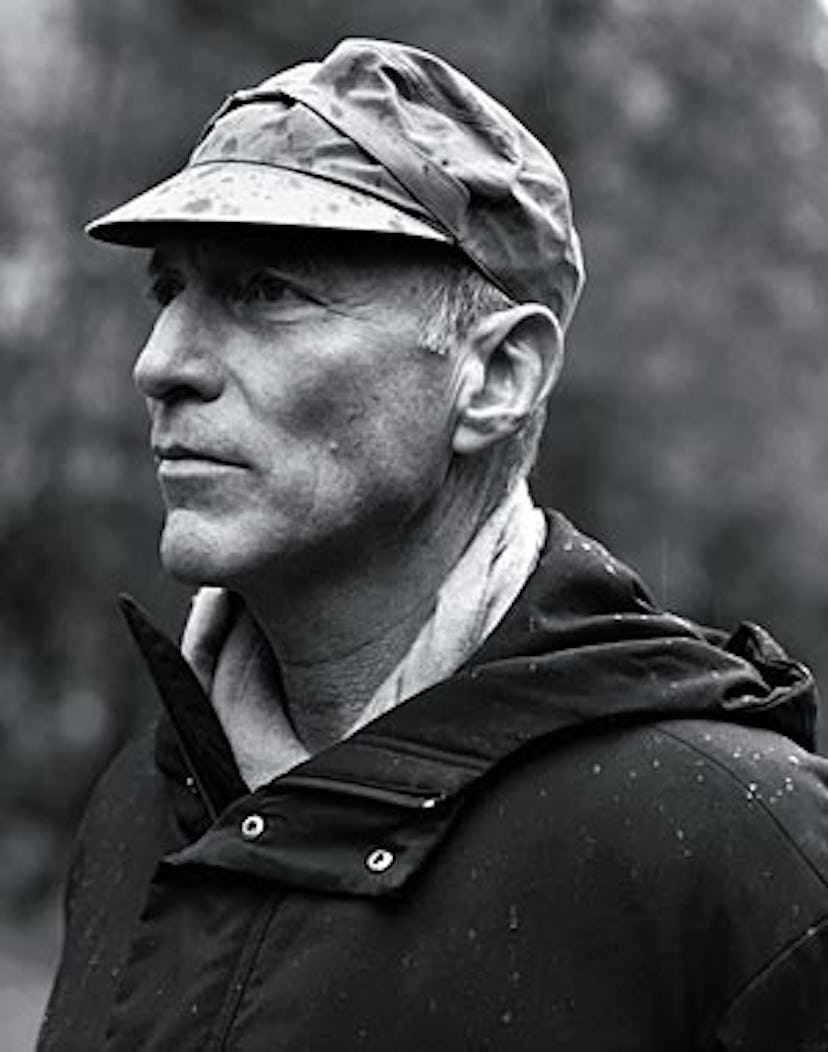

If Katz has a signature style, it’s a kind of glorified invisibility—a penchant for pure materials, clean lines and details so subtle that they don’t register as details. “An architecture of no effects” is how he himself describes it. As he gives a tour of Kiefer’s Paris lair, Katz, a tall, unflappable 66-year-old dressed in a navy shirt and Banana Republic pants, combines a folksy loquaciousness with occasional Zen-like pronouncements. “When people walk into a building, they should have a sense of something, but not of the building itself,” he says.

Like his designs, Katz’s career path evinces a deceptive simplicity: You don’t immediately see the effort and ambition behind it. While an undergrad at Johns Hopkins University in the Sixties, Katz was staggered by a Baltimore production of Edward Albee’s The Zoo Story. He found Albee’s address and convinced him to guest-lecture at Hopkins. Afterward, “Edward said, ‘If you’re ever in New York, come visit,’” he recalls. Katz managed to squeeze it into his schedule a week later.

After graduating, Katz moved to Manhattan, where he quickly zeroed in on some of the city’s most interesting people—Robert Indiana, Marisol, Andy Warhol—and made himself indispensable. “I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do,” he recalls. “So I would work in the studio, stretch canvases, run errands.”

Later, Katz worked for many years as a set designer and accidental architect, designing, among other spaces, the restaurant Chanterelle. (Because he’s not a licensed architect, he collaborates with established firms on most projects.) The first artist’s studio he worked on, in 1974, was a log cabin in New Mexico for his friend Agnes Martin. They built the whole thing together, but from the outset, Martin made it clear who’d be calling the shots. “Agnes was a do-it-yourselfer,” Katz says. “She told me, ‘The last studio I built, I built with a 12-year-old boy.’ I said, ‘Okay, Agnes, I understand the message here.’”

One reason for Katz’s success, clients say, is his sixth sense for grasping each artist’s wants and needs. “Bill genuinely knows the artists and has ideas about their work,” says Johns. “That allows him to interpret their needs in a meaningful way.” Von Furstenberg often teases Katz for being the ultimate “artist groupie,” though she points out that the admiration goes both ways. “The artists trust him and depend on him,” she says, calling Katz a “magician” who may have the best eye of anyone she knows.

It helps that Katz’s style is not about making its own grand statement but about letting the artwork be the star. And even that, Katz believes, is easily overdone. One of his pet peeves in museums and galleries is lighting that draws attention to art in an obvious way. “It looks like you are trying to sell something,” says Katz, who usually favors inexpensive bare bulbs.

For Phillips de Pury, of course, selling things is the raison d’être, but the auction house has nevertheless hired Katz to design all its spaces in recent years. Its new European headquarters, 40,000 square feet of mostly open-plan layouts, required an approach that was, in typical Katz style, both radical and understated. His main directive was to cut a 100- by 20-foot hole between the first and second floors, directly below a skylight of the same dimensions, so that the entire building would be flooded with daylight. “Bill has this holistic, almost shamanistic approach to figuring out a space,” says Rodman Primack, who runs Phillips’s London office. “It’s not about showing how clever he is. It’s about simplifying to the best extent.”

The Katz-designed interior of Mitchell-Innes & Nash gallery in New York

The ultimate test of those abilities was Kiefer’s Paris compound: a mega-artist’s Valhalla with endless white-walled studio spaces, vaulted underground storage areas and an electric ceiling crane that transports Kiefer’s monumental works from the basement to the street. When Kiefer bought it, the main building, despite its grand exterior, was a warren of tiny rooms and corridors. Luckily for him and Katz, most of the decorative details had already been destroyed, so they could achieve their desired spatial purity without breaking the law. Pointing to a limestone staircase, Katz says he filled in some large windows behind it because they’d been clumsily placed: “I said, that’s kind of an ugly little detail, isn’t it?”

“Bill is very minimal, very intellectual, and he doesn’t compromise,” says Kiefer. In one case that meant ripping out an elevator and reconstructing it a few inches to the right, to open up a stairwell.

“You know,” Kiefer says, “when you look at a room, there’s always something that bothers you. Maybe this door is too low, or that wall is not right.” Thanks to Katz, he says, “nothing in my home is disturbing me now. That’s important.”

Katz knows the feeling. Though he has a large apartment in SoHo, his spiritual home is an adobe building on a mesa near Taos, New Mexico. Katz built the place in the Eighties, in a spare style with no decor to speak of. Instead of ordinary mud, the walls are made from tierra bendita, revered for its healing properties, though of course you wouldn’t know that by its appearance. Aside from adding an Ellsworth Kelly sculpture to the courtyard and a Francesco Clemente painting in the bedroom (both gifts from the artists), he has kept the place exactly as is for 18 years. “I sometimes think, Isn’t it strange that I don’t want to change anything?” Katz says. “But I don’t.”

Phillips de Pury’s headquarters: David Lambert/Courtesy of Nissen Adams/Phillips de Pury & Company; gallery: Courtesy of Mitchell-Innes & Nash Gallery