As professional milieus go, the fashion world has never been known for its adherence to taboos. Indeed, it draws much of its mystique from the three D’s: decadence, debauchery, and drugs. There is, however, one D-word that this permissive tribe’s members tend to avoid—and that word, dear readers, identifies an attribute that yours truly has possessed, and worked assiduously to hide, for her entire adult life. My name is Caroline, and I am a D-cup.

Comical as it may sound, this is a hard confession for me to make. I came of age in the early Nineties, just as the underfed waif—exemplified by a scrawny new Calvin Klein model named Kate Moss—was replacing the previous decade’s glamazons as the fashionable feminine ideal. The resulting “heroin chic” aesthetic inculcated style watchers of my generation with the belief that, as fashion publicist Kelly Cutrone recently proclaimed, “Clothes look better on thin people. The fabric just hangs better.” Complicit in promoting this view, the fashion industry has held its models to increasingly dangerous physical standards—standards for which it has come under justifiable fire. Still, the view of emaciation as elegance has continued to reign supreme, and so too has the converse equation of voluptuousness with vulgarity. Although absurd, and in my case, self- defeating, these biases have driven me to hide my chest at all costs.

The operative term here really is “costs,” by the way. Over the years I have spent a fortune on sack dresses, unstructured jackets, and oversize cardigans—anything and everything I could find to mask my buxom upper body. A pricey effort, yes, but a successful one, given that every single friend to whom I have mentioned this article has reacted with some version of “No way do you have a big chest!” Prompting me in each case to make the same sheepish confession: “It’s true. I have stealth boobs.”

So why, you may ask, have I decided to bust out of the cleavage closet now? Well, I’d like to claim that I’m doing it in support of those models who have started speaking out about being deemed “too fat” for the runway. (Just to make clear what “fat” means in the fashion world: Three of the models so labeled—Lara Stone, Coco Rocha, and Filippa Hamilton—are five feet ten and a U.S. size 4.) But as much as I admire these young women’s courage, my inspiration came from a rather more improbable source. This season two of fashion’s most influential houses, Louis Vuitton and Prada, dispelled my mammary shame by celebrating, at long last, the belle poitrine. Miuccia Prada offered a typically thoughtful variation on va-va-voom, building up the bustline of otherwise primly elegant New Look–ish frocks with rows of frothy ruffles inflating the chest and pointy, exaggerated darts outlining the nipples. At Vuitton, Marc Jacobs also referenced the Fifties sumptuous hourglass silhouette but in a mode that was more showy than suggestive. Inspired by And God Created Woman, the 1956 French drama starring Brigitte Bardot, Jacobs paired wasp-waisted circle skirts with fitted bodices so tightly corseted and unabashedly cleavage baring that the models looked poised for an haute replay of Janet Jackson’s Nipplegate. As reported in Women’s Wear Daily, Jacobs had been “thinking about tits.”

And so, suggestible creature that I am, I began thinking about mine. In positive terms, that is. I wondered if perhaps my longtime habit of hiding my bosom was not—as Jonah Hill’s oversexed adolescent character notes in the film Superbad, about a girl who has gotten breast-reduction surgery—“like slapping God across the face for giving [me] a beautiful gift.” Certainly the models on the Prada and Vuitton catwalks made a strong case for buxom as beautiful. Each show featured a cast of voluptuous Victoria’s Secret sirens: Adriana Lima and Bar Refaeli at Vuitton, Miranda Kerr and Doutzen Kroes at Prada, Alessandra Ambrosio at both. Historically disqualifying for runway work, these models’ curves made the clothes look irresistible, luscious, downright sexy. More to the point, they made the clothes look suitable. One glimpse at Vuitton show opener Laetitia Casta’s abundant assets and I was transported into a parallel fashion universe: a place where designers had come to praise my bosom, not bury it. Literally and figuratively, my cup ranneth over.

I wish I could say that this is where my story ends—with me and a Vuitton steamer trunk full of D-friendly getups riding (bouncing!) happily off into the sunset. And for a while, despite all the heartbreak that fashion has visited upon me and my D-cups over the years, I really did believe that was going to be the case. When my editor had first approached me to write about the new curvaceousness, he made me an offer that I’d defy any fashion lover to refuse. “I’ll arrange for you to visit the Louis Vuitton showroom,” he said smoothly, like a benevolent stranger offering a child a nice, shiny lollipop. “They’ll let you look through the collection at your leisure, borrow the outfit of your choice, and wear it around town to see how it feels.” While he had me at “showroom,” “outfit of your choice” sent me over the moon.

The employees at the Vuitton showroom were faultlessly welcoming and kind. The samples I found there? Not so much. Sure, they were gorgeous. And exquisitely crafted. And sexy as all get-out. They were also, however, minuscule. Attired for the occasion in a white Empire-waist sundress with—an anomaly in my wardrobe—a plunging neckline, I did a quick visual comparison between the size of the clothes on the rack and the size of my rack. The former, accommodate the latter? My mind curled up in a sad little ball. You see, I don’t know much about geometry, or physics, or whatever cruel science it is that determines how volume G (gargantuan) fits into space t (teeny-tiny), or how mass M (massive) relates to object l (Lilliputian). But I do know—knew within minutes of sizing up those garments—that Operation “Outfit of Your Choice” was, well, a bust.

I should add that, for professionalism’s sake, I did retire to a changing room with the biggest of the handkerchief-size bodices: the only sample, a staffer informed me, into which an extra panel had been sewn “to fit one of the, um, curvier models.” On a still curvier moi, though, that extra panel did not make the difference between the top’s fitting and its not fitting. Rather, it simply meant that a mere 30 inches of my chest—as opposed to all 34 inches of it—remained, once the piece was “on,” wholly and humiliatingly unclothed. To stave off a crying jag, I forced myself to imagine that I was in ancient Crete, where the women wore dresses with bell-shaped skirts (check) and skintight bodices (check!) that left the breasts completely bare (BINGO!). But that fantasy lasted only as long as it took for me to change back into my own (I now understood) grotesquely large dress.

At this point you might surmise that fashion had become—to rephrase James Joyce’s description of history—“a nightmare from which I [was] trying to awake.” Yet even in my lowest large-chested moments, fashion for me has always, more than anything else, been a lovely dream. A dream of bodies not just disguised (as by my signature shapeless styles) but transfigured by the designer’s art, transformed by a miracle. And something quite like a miracle awaited me fewer than 20 blocks north of the Vuitton building. Moved by an instinct I still can’t explain, I took a cab straight from the scene of my disgrace to the Madison Avenue Prada store. I didn’t expect to find the new collection there: Like Vuitton’s, Prada’s fall line only existed, as yet, in too-small sample sizes relegated to a company showroom. It turned out, however, that along with just a few other branches worldwide, the Madison Avenue shop had stocked a capsule collection of fall dresses that boasted graceful crinoline skirts, nipped-in waists, and bodices made busty through exaggerated ruffles and darts. Against all odds, the store had one of those rare creations in my size. More amazing still, the salespeople let me borrow it—my editor’s promise fulfilled after all.

And although my new frock was made from the most glorious duchesse satin, I’d vote to name it “Princesse,” or better yet, “Queen of the Whole Bloody Universe, Thank You Very Much.” Because when I slipped the dress on and saw what it did for my body—how it accentuated and beautified the breasts I’ve always hated—that is exactly how I felt. I sailed out onto Madison Avenue and began walking. Catcalls, stares, and unsolicited offers of transportation (two gypsy cabs, one motorcycle) ensued, but to my surprise they didn’t discomfit or offend me. After decades of faux flat-chestedness, I discovered that I actually enjoyed looking like—being looked at as—a woman. My favorite reaction came from a handsome older gentleman on a Park Avenue street corner. Walking up beside me as I waited for the traffic light to change, he tapped me on the shoulder and said something that may sound creepy here but came across as strangely affirming and gallant. “Excuse me, miss, but I must tell you, you have the most distinctive kind of beauty, and I could use more of that in my life right now.” Reflexively, I turned my back on him and started hurrying down the avenue—modest old habits, after all, die hard. But even as I made my escape, I smiled to myself and thought: You know what, sir? So could I.

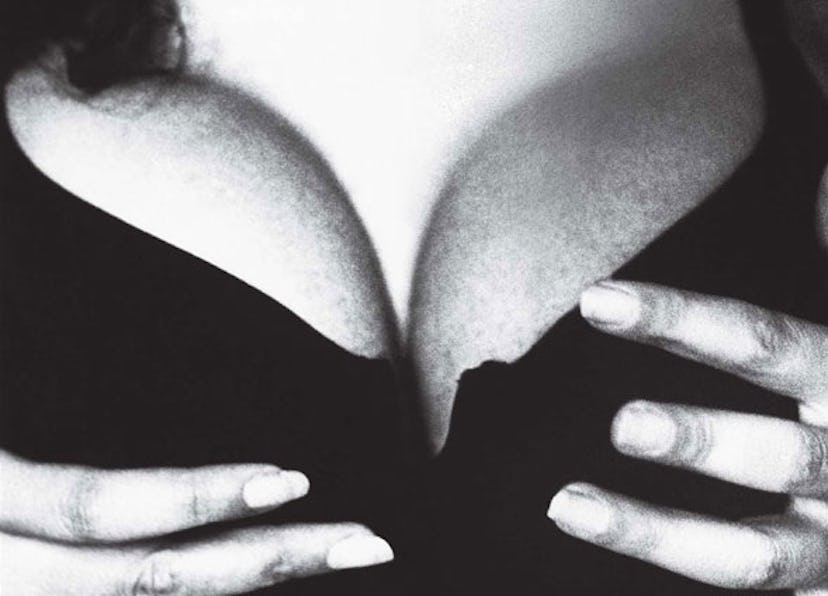

Ellen von Unwerth/Art & Commerce