Public Offering

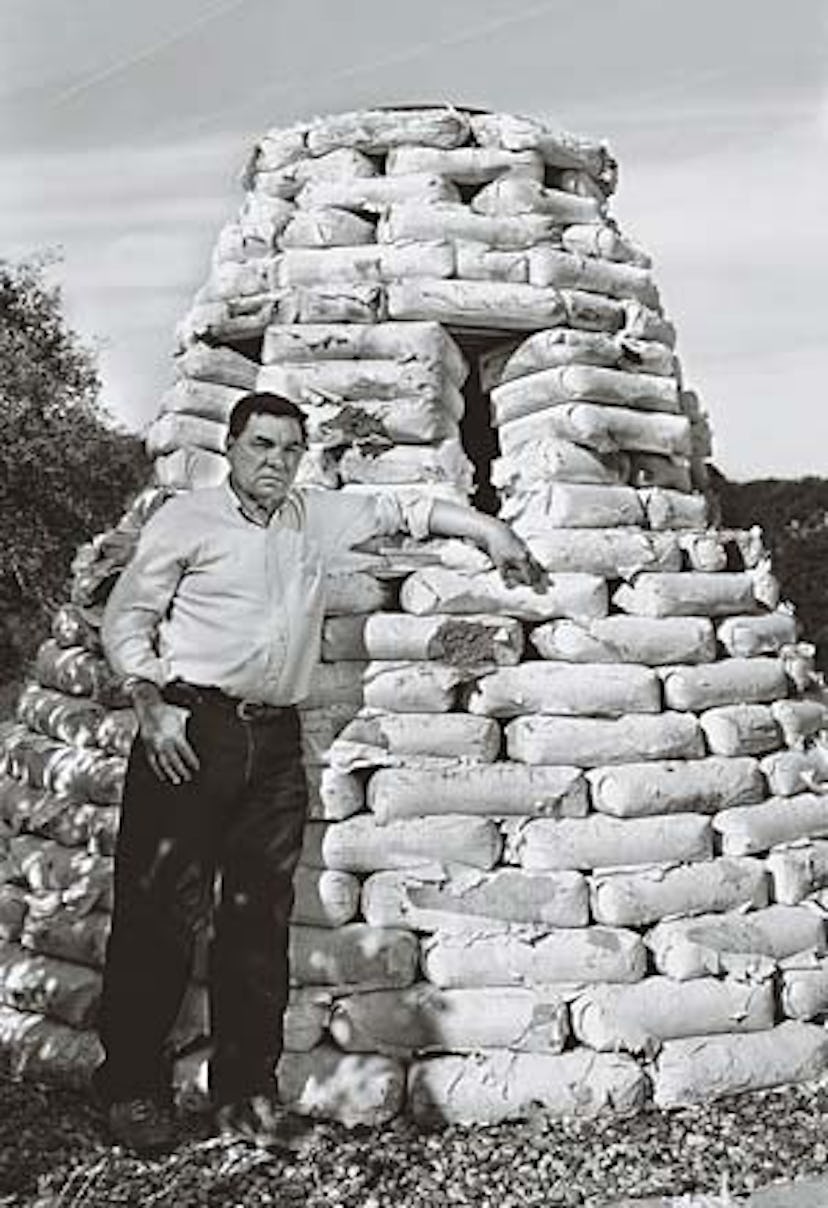

Sculptor Chris Burden, a cult figure on the L.A. art scene, unveils monumental projects on both coasts.

Chris Burden has, in the name of his art, been shot, nailed to the top of a Volkswagen Beetle and set on fire. He has crawled naked across broken glass, starved for 11 days on a desert island and stuffed himself into a student locker for an entire workweek. Burden, 62, originally trained as a sculptor at the University of California, Irvine, but the realities of his life in the Seventies forced him to exploit the most accessible raw material—himself.

From the performance Shoot, 1971, in which Burden was shot in the arm with a .22 rifle.

“One of the motivations for doing performances, which is going to sound dumb, is that when I got out of graduate school, I didn’t have any money,” recalls the artist at the Topanga Canyon compound where he works and lives with his wife, artist Nancy Rubins. “I really wanted to keep making art.”

These days Burden shows no ill effects from those earlier physical trials. Since the Eighties, he has mainly created outsize sculptures, and as he talks, a team of studio assistants are busy assembling his latest monumental creation: a 65-foot model skyscraper made with approximately one million stainless steel replicas of Erector set parts, which will be on view in June at New York’s Rockefeller Center with support from the Public Art Fund and developer Tishman Speyer. The tower recalls the fact that Burden wanted to be an architect before becoming an artist, and its title, What My Dad Gave Me, is a tribute to his engineer father.

“What I’m doing with these parts is kind of nuts,” says Burden, noting that A.C. Gilbert, who invented the Erector set in 1911, was inspired by that era’s novel steel architecture. “To me there’s a beautiful circle, in that I’m finally building a building with them.”

Given the dark mystique of his performances, Burden exhibits a surprising amount of gee-whiz enthusiasm in person, whether discussing Erector sets or the miniature train he’d like to build on his property. And unlike some artists, he is happy to talk about past work, including the notorious Shoot. Performed in 1971 during the height of the Vietnam War, the piece could not be simpler or more radical: Burden called a group of friends into a gallery to watch an assistant shoot him with a .22 rifle. “The bullet went into my arm and went out the other side,” recalls Burden, who essentially treated his body as a sculptural material to be reshaped by the bullet’s passage. “It was really disgusting, and there was a smoking hole in my arm.” The extreme act defined Burden’s career but to some seemed inexplicable, if not entirely deranged. The artist counters that the piece, in fact, was carefully rehearsed to minimize the chance of more serious injury. Cheating death was never the intent, he insists. “I was trying to think about a big fear,” says Burden. “Rather than turn from it, I was trying to face it, to eke something out of it, to doodle it out.”

Urban Light, 2000–07, now permanently installed at LACMA.

Burden’s “doodling” in performance art and video would earn him a cult reputation on the L.A. art scene. His longtime teaching position at UCLA, from 1978 to 2004, also ensured his influence on multiple generations of students, including sculptors Paul Sietsema and the late Jason Rhoades. Now, a spate of exhibitions is putting him before a much larger public and establishing him in the California pantheon alongside Charles Ray, Paul McCarthy and John Baldessari. “Chris’s performance work is iconic—it’s written into the textbooks,” says Paul Schimmel, chief curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA). “I think what we’re seeing now is the maturation of a career.”

New interest in Burden’s oeuvre began to crest last year, with the publication of a hefty monograph underwritten in part by Burden’s dealer, Larry Gagosian. Adding to the buzz, his seminal 1979 video work Big Wrench is on view through June 8 as part of the J. Paul Getty Museum’s exhibition “California Video.” In the film the artist recounts the quixotic narrative of Big Job, a junky tractor trailer Burden wanted to convert into an art project before running afoul of legal and financial obstacles. The show’s curator, Glenn Phillips, suggests that the piece reflects a pivotal moment in the early Eighties when artists shifted away from abstract gestures toward personal narrative, and away from conceptual work toward marketable objects. In Burden’s career, the Big Job story also illustrates the artist’s path from performance back to sculpture, which would grow in scale to encompass what Public Art Fund director Rochelle Steiner calls “the grand gesture.”

“From the beginning of his career, Burden’s work has been about looking at limits,” she explains. “How tall can I make a tower with Erector set parts? What are the limits of my endurance? His curiousity is about how far you can take things—politically, socially, physically—and his studio is almost like a laboratory where experiments take place.”

In addition to Burden’s five-ton Medusa’s Head (1990) and his Erector set scale models, a prime recent example of his monumental work is Urban Light (2000–07), which was installed at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) earlier this year. The outdoor piece, 60 feet square, brings together in tight formation 202 antique L.A. streetlights from the Twenties and Thirties. Burden came across the first two at a flea market seven years ago and, caught by the collector’s bug, went on a buying spree that eventually led him to mortgage his house to cover the nearly $2 million cost of buying and restoring the collection. Explains Burden, “To me these poles are an early form of public art.” Frank Gehry wanted to acquire part of the set for a project in downtown L.A., and CAA considered buying a few to adorn its new Century City headquarters. But Burden decided to keep the group together. “I think that I’ve made a building without walls and a roof of light,” he explains. “It’s like walking through the Acropolis or something.”

“It’s a monument of everyday materials, the antimonument monument,” agrees LACMA director Michael Govan. “There’s a ceremonial quality to the work. The Met has its fake columns and pediments. Here are our street lamps, our temple.”

Burden was born in Boston and describes his decision to attend Pomona College, where he majored in art, as spur- of-the-moment. During graduate school at Irvine, he started making odd contraptions resembling exercise machines that viewers were meant to interact with. Frustrated that people often failed to understand that, as he puts it, “the apparatus was not the art,” he staged one of his first performances in 1971 to demonstrate the idea. Inspiration came from a bank of lockers at Irvine, when Burden realized that instead of building a sculpture for others to engage with, he could simply put himself into a ready-made box: “Me inside the locker was the art.” He rigged a five-gallon bottle of drinking water above him, an empty five-gallon bottle for waste below and, at 8 a.m. on a Monday, climbed inside. Eventually news of the performance, called Five Day Locker Piece, trickled out, and despite alarms raised by the administration, Burden stayed there until Friday at 5 p.m. “That was a real turning point in my career,” says Burden. “I realized that I could make art by doing something as opposed to making something.”

Over the course of the next decade, Burden created numerous other performance pieces. Most were poorly documented, although an eight-second film clip of Shoot can now be found on the Internet—an early harbinger of downloadable spectacles of violence. Other works were equally ahead of their times. B-Car (1975) was an ultra-lightweight automobile designed to run 100 miles on one gallon of gas, while Chris Burden Promo (1976) was a guerrilla advertisement that aired on local late-night television. The names da Vinci, Michelangelo, Rembrandt, van Gogh and Picasso flashed against a blue screen, followed by a sixth: Chris Burden. “If I was a billionaire’s son and I played that commercial for five years, then guess what?” Burden says. “For the man on the street, my name would be right up there with Michelangelo.”

Burden admits that such ephemeral works were financially “suicidal,” and through much of the Eighties and Nineties, he relied on NEA fellowships and his professor’s salary to supplement his income. He’s frank about the downside of teaching—“I got tired of raising other people’s children”—and why he and Rubins, also on the UCLA faculty, retired abruptly after a student brought a very convincing replica of a gun into a performance-art class. Burden’s objections have led some to brand him a hypocrite, but he fires back that Shoot took place in a private gallery, not in a public classroom. “Students do all kinds of crazy things,” Burden explains. “That’s to be expected, right? But there’s a whole level of decorum that applies to everybody. So when the university chose not to take any action, I couldn’t be a part of that institution anymore.”

As much as Burden seems to enjoy talking about his own wild years, he has zero interest in re-creating his early performances. He doesn’t want anybody else to do them, either. In 2004 he turned down artist Marina Abramovic’s request to stage her own version of Trans-fixed (1974), in which Burden was nailed, through his palms, to a Volkswagen Beetle. He calls the idea of a reprisal “inane.”

“I never thought of my things as theater,” says Burden, a bit baffled that anyone would fail to understand. “They were like scientific experiments. There’s no second time. The first time you do something only happens once.”

Photos courtesy of the Gagosian Gallery and Los Angeles County Museum of Art.