Where In The World Is David Adjaye?

What do Manhattan’s most radical new residence, D.C.’s National Museum of African-American History, and the Ghanaian home for a Nobel Peace Prize winner have in common? All were designed by David Adjaye, the Tanzanian-born architect who is suddenly everywhere at once.

A few years ago collector Adam Lindemann and his wife, Amalia Dayan, an art dealer, began thinking about a new home for themselves and their sizable collection of contemporary art. They had in mind something iconic, something that would make a statement—something, say, on the order of such modernist masterpieces as Pierre Chareau’s Maison de Verre in Paris or Philip Johnson’s Rockefeller Guest House on East 52nd Street in Manhattan. But along with providing space for art, the house had to be livable. The couple own large, commanding works by the likes of Tim Noble and Sue Webster, Maurizio Cattelan, and Urs Fischer. Their collection needed both ample room to be experienced and architecture commensurate with its bravado.

Lindemann, a private investor and a son of billionaire George Lindemann, had purchased a wreck of a carriage house on East 77th Street with the intent of tearing it down, leaving in place only the building’s landmarked facade. “We wanted to push the envelope of what was possible within a little piece of New York City,” he says. While the couple had their pick of big names for the job, they chose David Adjaye, a Tanzanian-born British architect of Ghanaian descent, then a rising star in the UK but little known anywhere else. “It was a bit of an experiment,” Lindemann says. Adjaye, who was working on Denver’s Museum of Contemporary Art, hadn’t yet unveiled a major building in the U.S. To Lindemann and Dayan, though, that was part of his appeal: He was innovative, a new name, and, above all, had serious art-world cred, having made his mark designing gritty, luminous homes and studios for a number of the artists that the couple collected. (Adjaye was also a fixture at London’s Frieze Art Fair and the Venice Biennale and had collaborated on pavilions for artists Chris Ofili and Olafur Eliasson.)

At their first meeting, however, the architect told Lindemann and Dayan that he probably wouldn’t take the job. “I wasn’t convinced if [Lindemann] wanted to make a project that explored ideas about art and architecture, or if he just needed a stylish home by a trendy architect,” Adjaye explains. “I don’t want to do stylish homes.”

Charismatic and engaging—if fond of architectspeak—Adjaye, 44, is a rarity among his peers, and not just because he’s a black architect working in a predominantly white world. A self-described Robin Hood, he balances spare, geometric private retreats and galleries for art-world A-listers with socially driven public buildings designed to function as urban catalysts. His much lauded Idea stores in London’s East End reimagined the modern library as a bustling community center and helped earn Adjaye an OBE from the Queen in 2007 for services to British architecture. Spend five minutes with him, in fact, and he’ll persuade you that architecture can spur communities to become as open and democratic as an outdoor market.

Since the architect launched Adjaye Associates in 2000, his rise has been meteoric, especially in a profession known to award big-ticket commissions late in a career: He has designed the Nobel Peace Center in Oslo and a home for a Nobel Peace Prize winner in Ghana; the Moscow School of Management; and flood-resistant houses in New Orleans for Brad Pitt’s Make It Right Foundation. (During the same period, Adjaye made a point of visiting all 53 capitals on the African continent, intent on photographing its overlooked modernity and variety.) Now, though, after edging out vets Lord Norman Foster and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, he’s immersed in the largest and most prestigious project of his career: designing the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture—what is likely to be the last major building to be erected on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

Adjaye is tall and solidly built, with a shaved round head and a jawline ridged with a pencil-thin beard that curls around his upper lip. When he speaks, he uses his long, elegant hands expressively, as though drawing in space. On a sunny day this past November, in the office on Canal Street in lower Manhattan that he shares with industrial design star Yves Behar, Adjaye was wearing his uniform of black pullover, narrow black trousers, and pointy black shoes while spooning white bean salad and artichokes out of Dean & DeLuca take-out cartons. Behind him, on spotless white shelves, were samples of the organic cotton underwear he designed for Behar’s PACT project to fight deforestation throughout Africa. The night before, he’d spent his first Halloween in New York. “It was completely bizarre—kind of shocking, really,” he says. “Just a complete hedonistic moment, and naughtiness everywhere.”

What convinced Adjaye to take on the Lindemann-Dayan house was the couple’s kinship to the artists who are among his closest friends. “Amalia mentioned all the right names,” he says, punctuating his conversation, as he often does, with easy laughter. “I felt she had empathy with my language, because she liked the work those artists did, and she liked the places I’d made for them.”

It’s a language developed in London’s formerly unfashionable East End, in the places he made for the soon-to-be Young British Artists he had met at the Royal College of Art in the early Nineties. His first client was Ofili, whose dealer, he recalls, had just given him “some derelict rundown”—a former sweatshop she’d bought at auction—to use as a live-work space. When Adjaye bumped into Ofili on the street one day, he suggested they go have a look, and on the spot, as Ofili tells it, Adjaye offered to make him a studio and place to live. Ofili later gave him a painting for the work he’d done.

The building’s roof was gone—Adjaye remembers pigeons flying around—and only an interior staircase and bits of floor remained. “Chris wanted to respect the nature of the building, not fight it,” says Adjaye, who kept the staircase and rebuilt around it. “His aesthetic is to try to search for the essence of things. So luxury was in the plainness of things—and that position rhymed very much with my own sensibility.” At the time Ofili, like the other artists Adjaye knew, was rethinking what art could be made of: While Ofili was using elephant dung in his paintings, his friends Noble and Webster were making works out of recycled trash. Forced to come up with inventive solutions himself, Adjaye eschewed high-end materials in favor of simple, familiar ones—concrete, plaster, glass. Their lack of refinement, as he saw it, packed a visceral punch.

What Adjaye ultimately developed with Ofili was a way of working that brought an artist’s sensibility to his architecture. Seeing one’s home as a refuge from urban life, a kind of emotional incubator, Adjaye created a sensuous internal world hidden from the street, with the spaces for living and artmaking connected in unexpected ways. (Ofili’s studio, for example, was designed with a factory-glass-brick ceiling and sat directly beneath a cubelike glass conservatory open to both the back and the sky.) The experience underscored Adjaye’s growing realization of how profoundly architecture shapes our psyches on an almost granular level.

“That house is really the DNA for almost all of the artist houses that I did,” Adjaye says. “It was a complete collaboration. In the beginning I wasn’t very articulate; I needed people who understood what I was doing rather than what I was saying. I’d draw something, and Chris would say: ‘Yeah, that’s amazing. Let’s go.’ Artists nurtured me to be confident about the language I was developing.”

A dozen or so years later, Adjaye is now “the model of the new architect,” says Aaron Betsky, director of the Cincinnati Art Museum. “He’s not just someone who makes abstract forms wearing a conceptual white lab coat. He’s well versed in contemporary art and architecture and is part of a global culture mash-up in which all the various arts and design fields are talking to each other.”

Adjaye has gone on to collaborate with Ofili on projects ranging from “The Upper Room”—13 paintings of rhesus monkeys displayed in a chapel-like environment—to a new studio and a beach house for Ofili in Port of Spain, Trinidad, now under construction. “We sometimes speak about how things are best designed on the run,” Ofili says. “Walls get built and knocked down and reshaped. It’s a bit like making a painting with him, because you can change it as you go along.”

In the case of Dirty House, the studio-home Adjaye designed for Noble and Webster in East London in 2002, it was more a case of pay-as-you-go. The couple, not yet supernovas, invested as much as they could up front and then made their own work on the construction site to pay for the house’s completion—literally turning trash into cash. “Halfway through the project I’d say, ‘Okay, David, I’ve got enough money for a kitchen,’” Webster recalls. “It focused their minds on the value they needed to make,” Adjaye says, laughing. “Production follows need.”

Dirty House bears many of what have come to be known as Adjaye trademarks: Its cantilevered roof appears to float in space, and the building’s exterior, painted “the color of David’s skin—we actually color-matched him,” says Webster (though Adjaye disputes this), looks dark and foreboding from the street. Webster describes it in an e-mail as “disappearing into the night when darkness falls, with mirrored windows that sink like eye sockets of a skull.” Inside, though, she hastens to add, the space is “bright white and airy—a softer center once you’re able to penetrate the crust.”

Adjaye himself embodies similar contradictions. “His public persona is bulletproof,” Ofili says, “whereas his private persona has more fragility.” Artist Lorna Simpson, for whom Adjaye designed a four-story studio in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene neighborhood—his first U.S. commission—describes Adjaye as funny and down-to-earth. “David’s personality belies his ambition and the level of work he’s done,” says Simpson, who shares the building with her husband, photographer James Casebere.

The watch Adjaye wear has three faces, each set to a different time zone: London, New York, and “wherever I happen to be,” he says. This past fall that could have been anywhere from Qatar to Berlin to Denver. Thelma Golden, a close friend and the director of the Studio Museum in Harlem, says she ends each e-mail to Adjaye with “Where are you?” His London apartment is more way station than home; even some of his closest friends haven’t seen the inside of it. “He’s like a member of the family, but we have no idea where he lives,” Webster says. “I think out of his suitcase, doesn’t he?”

The apartment, in a late-19th-century building near the British Parliament in Westminster, a neighborhood steeped in tradition, may seem oddly located for a contemporary architect. (“It’s not where you think,” Adjaye said. “You’d never believe I live there.”) His younger brother, Peter, a London DJ and teacher, says Adjaye was attracted in part by the area’s symbolic meaning: “He’s very much into leaving a permanent mark and placing himself close to where the very powerful decisions are made.”

The apartment is a “magpie space,” Adjaye explains, “filled with things that act as my triggers and reconnect me to places.” These include books, models of various architectural projects, artworks by friends he has designed homes for, even vials of sand from various deserts he’s been to. Also vying for space is a vast collection of jazz, funk, and soul albums dating from his own stint as a DJ, when he was a teenager. Adjaye is now weighing the purchase of an apartment near his Canal Street office in New York, an area teeming with the kind of urban vibrancy that inspires him. Located in a former metal factory, it “allows me the most flexibility to define myself,” he says. “I can’t slip into an apartment that’s done already; I need a neutral container. I’ve become more spatially sensitive.” He’s also learned that his business isn’t recession-proof: In 2009, after several commercial projects were canceled, Adjaye had to lay off staff and restructure more than $1.6 million in debt.

On a cloudy, end-of-November day, Adjaye and I take the subway from Canal Street to the Upper East Side so he can give me a tour of the Lindemann-Dayan town house. The couple and their two young daughters moved in more than a year ago, but until now no pictures of it have been published. (Later this month Rizzoli will publish David Adjaye: A House for an Art Collector.) The house is concealed behind the facade of an 1897 carriage house, making the property virtually indistinguishable from its stately neighbors. Step through the gate, though, and there looms a black concrete box—a nod to Marcel Breuer’s Brutalist Whitney Museum, located a few blocks away—as boldly unorthodox as the art within.

To enter, you must first cross an open courtyard flanked by cascading pools of water. When a landmark designation forced Adjaye to keep the facade, he came up with the idea to create a floating library on the second floor, which, when viewed from the street, looks to be a room inside the main house. In fact, the library is tethered to the new house by a glass bridge leading to the living room. And crossing that see-through slab is not for the faint of heart: There’s a 40-foot drop beneath it, and as you look down you see Maurizio Cattelan’s Daddy, Daddy (2008), a life-size sculpture of a dead Pinocchio floating facedown in one of the pools.

Adjaye delights in such vertiginous perceptual shifts and off-kilter geometries. His buildings aren’t experienced all at once—they’re revealed in a series of “aha” moments that occur as you spend time in them. “Nothing is where you think it should be,” he says, pointing out skylighted spaces and trapezoidal cuts in the walls that frame views of inner courtyards and the rooms beyond. “This is a house that looks inward, not outward to the city.” Rather than put a roof over every inch of available space, Adjaye made open-air courtyards in the center of the two connected structures he designed, “to bring nature right into the heart of the house.” As if on cue, it begins to drizzle just as we wend our way outside. “Sorry you’re getting rained on,” he says, “but it’s more beautiful to me like this. It’s part of the gritty reality of it—not just pretty sunshine.”

Though a friend of Lindemann and Dayan’s describes the house as “a moated dungeon,” Dayan says it feels like a medieval castle. To Adjaye, however, it’s simply “a gallery with a home welded around it.” The front door opens to the gallery, where, hidden behind one wall, a narrow staircase climbs to an expansive double-height living room. “It’s not a set,” Adjaye said. “It’s about making environments for art.”

That art is anything but cozy. In the living room alone, there’s an enormous Damien Hirst painting of cancer cells studded with scalpel blades, an Urs Fischer skeleton work, and another life-size sculpture by Cattelan, of a female artist lying in a crucifixion pose in a coffinlike art crate. “It’s very much an alternative view of the world,” Adjaye says of the couple’s collecting taste. “I share some of those concerns. For me, it’s about not glossing over the brutal reality of life. I wanted to explore what that could mean.”

Just what that means in a custom-built town house off Park Avenue is that the materials are used in a way that Adjaye says “always feels raw.” So the gallery floor is oil-stained travertine—the kind of limestone that builders reject—while the black concrete is as rough as can be and sliced in several places to expose the stones inside. “It’s all imperfection,” Lindemann says, “which relates to the artists I like who have a more handcrafted, rougher aesthetic.” The idea was to let Adjaye lead, Dayan told me, recalling how the architect convinced them to go with dark hand-poured concrete by showing them the 1956 Venezuela Pavilion (designed by Carlos Scarpa) while the three were attending the 2007 Venice Biennale. “We fell in love with it, but we still had no idea what to expect,” she says. “Now my favorite thing about the house is the black concrete—it’s austere and warm at the same time, in a very strange way. The surface changes. It’s like an amazing painting.”

The house is not all tough veneers, though: The library is lined in walnut, the master bedroom in tiger wood, and both have such an intimacy of scale that they feel like urban sanctuaries. However radical the house, Adjaye insists that he opposes “domestic tyranny”—that is, when the architect’s vision is so rigid that any deviation from it means everything is spoiled. Not only was the gallery designed to accommodate changing exhibitions (to allow Lindemann “his curatorial moments,” as Adjaye puts it), but recently the architect arrived to find Dayan hosting a women’s yoga class there.

Architects, of course, are peripatetic by trade, but even by the standards of a new global age, Adjaye is remarkably well traveled. He was born in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, to Ghanaian parents who both were the first in their families to leave their village “to go global,” as the architect says. Adjaye’s father was a diplomat flush with the promise of a newly independent Ghana, and the family was regularly on the move from one foreign posting to the next. By the time Adjaye was 12, he’d lived in Ghana, Egypt, Lebanon, and Saudi Arabia in mostly modernist bungalows that came with a staff. He and his brothers, Peter and Emmanuel, learned early and often how to adapt. “It was very traumatic moving around, and it made us completely tight,” Adjaye says. “My whole beginnings are about instability through cultural or religious friction. I still remember being in Beirut and playing on my balcony, watching the Syrian tanks roll up.”

Not surprisingly, his childhood travelogue left a lasting impression. “I was always very aware of the atmosphere of places,” he says, recalling how the African continent in the Seventies was undergoing convulsive change. “There were these incredible new skylines as towers were being built out of the forest, and a metropolitan urbanism was emerging. I was smack in the middle of that.”

The family stopped moving around for good after Emmanuel, then five, fell into a flu-induced coma in Ghana that left him mentally and physically handicapped. “It changed the entire dynamic of the family,” Adjaye says. “My father gave up his career and took a local posting in London so my brother could go to a special school. We retreated from a porous public life to a hermetic one.”

Arriving in London in 1979 at age 13, Adjaye discovered that his cosmopolitan upbringing clashed with the provincial outlook of his schoolmates. “Nobody had ever traveled. Ever. It was a complete mind bender,” he says. For the first time he encountered racism. “Kids would say, ‘Go back to Africa,’” recalls Peter. Though the brothers spoke in American accents honed at an international school in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, they were treated as working-class immigrants. “There was a huge disconnect,” Adjaye says. “I wanted to fit in and couldn’t.”

A stint in art school eventually led him to architecture, which, he says, “connected me to the profound things I loved as a child—my memory of places.” But it was visiting Emmanuel in a home for the disabled that clarified his direction. “These people were all disconnected from society, and I thought it was inhumane,” he explains. “I suddenly found the social responsibility of architecture very compelling.”

Adjaye soon forged ties with the art world at the Royal College of Art, where the liveliest conversations always seemed to take place in the college bar. “The whole YBA scene was in and out of that world,” he says, “and we became a kind of gang.” His first projects with classmate William Russell included a set for a Chrissie Hynde music video, a noodle bar in Noho, and a house for their chum Alexander McQueen that was never built. “There was a real sense that we were going to reinvent the world,” the architect says.

Finding his place in that world, however, was complicated. Architecture schools taught only from the canon of the West, and Africa was left out of the conversation—“except for the pyramids,” he says wryly. “I thought the whole notion of my upbringing and where I came from was not relevant to this discourse. And I was very traumatized by that.”

In traveling back to Africa in 2000, Adjaye found his way forward. His girlfriend at the time worked for the United Nations, and he’d visit her on her various postings, hiring cabdrivers as his tour guides, telling them that the meter could run, as he puts it, “as long as they showed me everything.” Soon he had a rich data bank to mine. “I realized there was a lack of imagery in the world about an urban Africa. I wanted to dispute any sense that it’s all village and rural, so I started showing my photographs to people. They were like, ‘What the hell? This is what Addis looks like?’ Nobody had any idea. Their image was either poverty or fiction.”

In Africa Adjaye became intrigued by the way life spilled from the home into the marketplace, where all strata of society seemed to mix. “You’ll have this wealthy ambassador’s wife trucking through with her staff, as well as the girl who is selling stuff,” he says. “I was fascinated by how the market makes a democratic commonality.”

If Adjaye’s private homes are about retreat, his public buildings are all about engagement. Like his first Idea Store—a glass-fronted library built in 2005 in Whitechapel, a neighborhood that’s home to thousands of immigrants from Africa and Asia—Adjaye’s design for the National Museum of African-American History and Culture does away with the 19th-century notion that civic buildings are meant to ennoble. “I’m not interested in these threshold moments where you rise up to enter,” he says. “We’re done with that. I don’t want to go up to the temple.” Adjaye’s glass-fronted main hall, flush with Constitution Avenue, “hoovers you in,” he says, showing me a model of it in his New York office. “It’s a terrible term, but it’s very deliberate—and it wasn’t in their brief.” The building, essentially a three-tiered crown atop a stone base, is clad in a perforated bronze skin that provides what the museum’s director, Lonnie G. Bunch, calls “something that’s been overlooked—a dark presence on the National Mall.”

Adjaye’s design looks to both Africa and America, drawing inspiration from sources as diverse as the porches of the Old South and tribal Yoruban art. “It recalls the crowns on West African sculpture,” Bunch explains, “but also suggests upraised arms in prayer, which gives a strong feeling of America. It’s a wonderful blend of who we once were and who we are today.” For his presentation to the selection committee, Adjaye ended his virtual fly-through of the building with an image of the museum glowing at night at its prime location on the Mall adjacent to the Washington Monument. “That was really the topper,” says Bunch, who chaired the jury that selected the winning team. “It made me realize that he understood how his building has to be distinctive, but also dance with the other buildings on the Mall.”

A major museum—let alone a national one—is the defining commission for any architect. For Adjaye it’s also deeply personal, because it “absolutely describes the kind of trajectories I’ve experienced,” he says, adding that from the beginning he saw the museum as being about cultural identity, not just African-American culture. For the museum to be successful, it has to resonate equally “for an African-American kid from Arizona and the Kenyan kid who’s just arrived from Mombasa for a holiday in D.C.

“You’re sort of writing a giant hieroglyph of your civilization,” he continues. “It’s the stuff of architectural dreams—or the perfect architectural tragedy.” Whatever the outcome, the museum’s high profile (and estimated $500 million budget) is sure to bring Adjaye greater scrutiny, something he’s been growing accustomed to as a black architect. “The problem with being a trailblazer,” he says, “is that you get a lot of attention, but you also have people asking, ‘Does he deserve it?’ Who you are is being processed through it all the time. You have to really be on your game, because everything you’re doing is a kind of prototype.” Ground breaking is scheduled for 2012, and the museum is slated to open in 2015. “I was Peter Pan when I started,” Adjaye says, referring to the tricky business of having to navigate a morass of agencies in the nation’s capital. “Now I’m growing gray hairs.” In the meantime, he’s designing seven buildings the size of city blocks in Doha, Qatar, as well as low-income housing in Harlem’s Sugar Hill neighborhood.

In November I joined Adjaye for a birthday party at nearby City College for artist Faith Ringgold, for whom the institution’s children’s museum has been named. Adjaye had been asked to give a toast and was “nervous as hell,” he admitted. “I hate public speaking.” As we walked near the site, he mentioned that he had come up with the idea for the building’s rose-patterned facade while listening to Aretha Franklin’s cover of “Spanish Harlem.” “I listen to a ton of music,” he said. (When he designed a record store in London recently, he bartered his design fees for free CDs for the next decade.)

These days Adjaye is reading books by social thinkers—“people formulating ideas about the world.” Novels are reserved for holidays, something the architect says he doesn’t have much of anymore. He flew to Madagascar for his last vacation a year ago, and soon he’ll be off to Morocco for another. First, though, he was heading to Art Basel Miami for a dinner in honor of industrial-designer-of-the-moment Konstantin Grcic that he didn’t want to miss. “You’d think I’d never want to get on a plane again,” Adjaye says, “but my favorite thing is to drop myself in a place and just absorb. A new way of looking at the world—that thrills me. Really thrills me.”

Artchitect David Adjaye

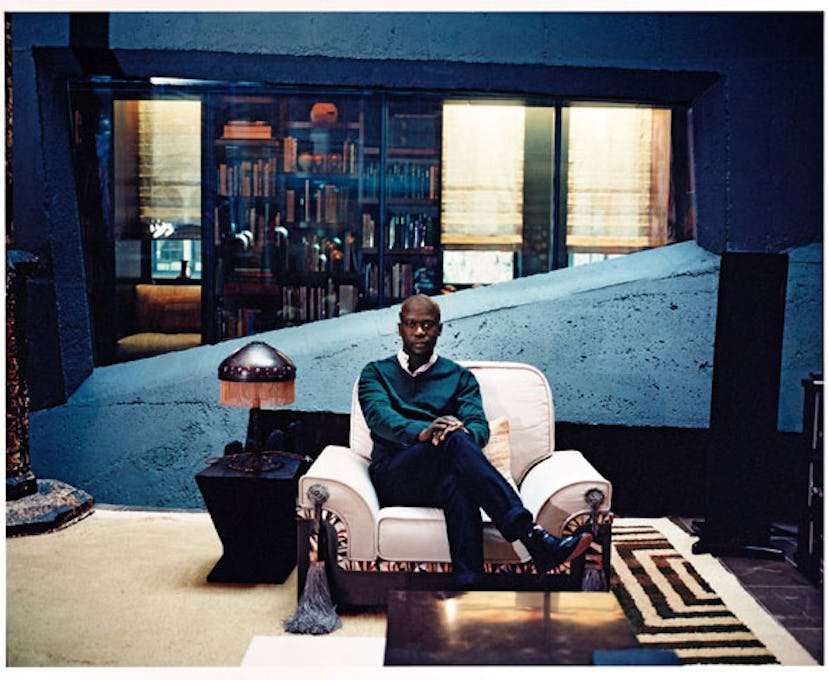

Adjaye in the living room of the Lindemann-Dayan house on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

The Lindemann-Dayan house’s open-air atrium and fountain, with a staircase leading to the rooftop garden.

The bronze front doors open to the first-floor gallery.

Adjaye’s design incorporates trapezoidal windows and skylights.

The Lindemann-Dayan house’s landmarked facade disguises Adjaye’s striking black-concrete box.

London’s Dirty House, 2002

Adjaye’s Moscow School of Management in Skolkovo, 2010.