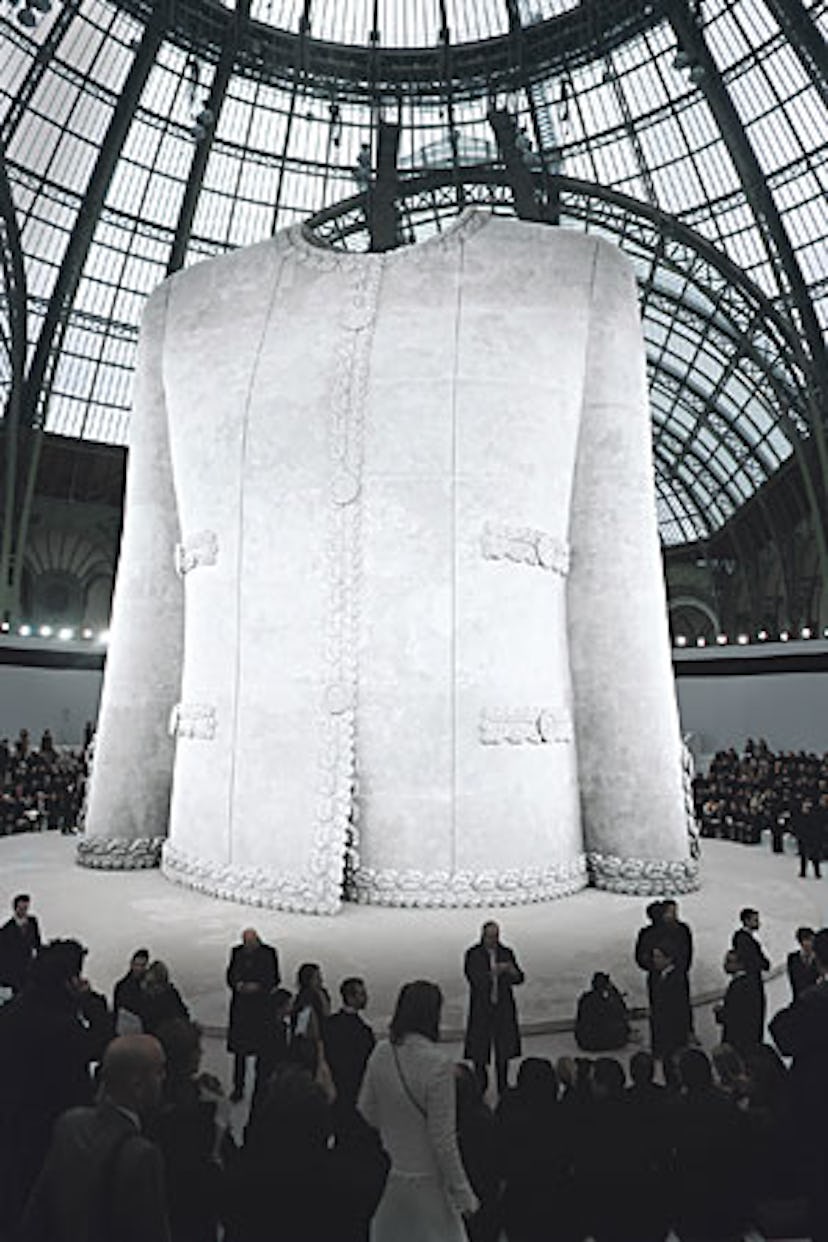

Pity the tree that falls unheard in the forest—and the designer with a plain-Jane runway show or convivial showroom cocktail party. Making an impact with a new look or product is no small feat in a luxury fashion world populated with huge rotating Chanel jackets, merry-go-rounds, Dior runways the length of football fields (at Versailles, no less) and building-size images of David Beckham in his skimpy Emporio Armani skivvies.

“Everything these days has to occur in a bigger way in order to get people’s attention; the volume on everything has to be turned up,” says Marc Jacobs, who had Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth writhing onstage at his latest fashion show in New York—and sent radically high heels stomping down Louis Vuitton’s runway to blistering techno. “You have to build a bigger, better, faster, harder [fashion] house.”

An ice replica of Cartier’s Paris flagship in Harbin, China.

Welcome to an age of extreme marketing that has today’s biggest luxury players forever raising the bar with events, shows and advertising of the jaw- dropping ilk. Need to launch a jewelry line? How about partying with Naomi Watts and Juliette Binoche at the foot of Switzerland’s most iconic mountain as you’re serenaded by Bryan Ferry? (Hello, Montblanc!) Celebrating a relocated Paris boutique? How about an intimate concert with the astonishingly talented but mercurial, notoriously unreliable Amy Winehouse? (Thank you, Fendi!) Eager to remind people about your firm’s roots in travel goods? How about a stirring and painterly 90-second commercial with music by Oscar-winning composer Gustavo Santaolalla, of Brokeback Mountain fame? (Brought to you by Louis Vuitton.)

“You have to find a way of projecting your own distinctive voice through the background noise,” says Giorgio Armani, a pioneer in leveraging his celebrity following, from dressing Richard Gere in sexy suits in American Gigolo to having Beyoncé Knowles wail about diamonds for the latest Armani perfume. “Fashion is all about evolution and change, and so it is only to be expected that we should change the way we bring our message to the customer.”

A handful of leading luxury fashion and jewelry houses, armed with big budgets and bold ideas, are out to dazzle their clients with attention-getting spectacles that express excellence, create excitement and fan that all-important urge to spend. “We want our customers to feel inspired and aspire to engage with the brand,” says Maureen Chiquet, global CEO of Chanel, which has been one of the prime champions of the bigger-is-better trend with its massive shows and exhibition projects. “There is no hidden purpose or marketing plan behind our events; they are the modern expression of Chanel as Karl Lagerfeld sees it. I am always surprised at how effortless it all looks.”

Lagerfeld says that he spied the cinematic potential in fashion more than three decades ago. He built his first set for a runway show back in 1974, when he was still designing for Chloé; it was a re-creation of a trellis garden at the Palais de Congrès in Paris, with one model coming out holding a green parrot. Today, the designer’s sets for Chanel are monumental: a 105-foot tower shielding a winding staircase for couture one season; for ready-to-wear, a bow so gargantuan it made a Richard Serra sculpture seem puny. In February the carousel that whirled under the soaring dome of the Grand Palais in Paris weighed 10 tons and took workmen five weeks to carve and nine days to install—all for a single use. The 66-foot-tall Chanel jacket created for January’s spring couture show—with models strolling out from its placket—was also built for 15 minutes of glory, wrought from wood, plaster and polyester resin and artfully painted to look like stone.

Lagerfeld, who is obsessed with photographs and video, reasons, “You make a movie, you have to build a set.” And he’s right: Fashion is its own movie. His shows get lots of airtime and are also broadcast in Chanel boutiques around the globe. A plain white wall as a backdrop just doesn’t cut it. “We live in a world of image, of television, of things seen on screens; empty screens don’t look so good,” Lagerfeld says, his eyes shielded by mirrored, wraparound Michalsky sunglasses. “This is something big companies do.”

Last October the designer took the notion of bigness to a new zenith for Fendi, sending the spring collection down the Great Wall of China, arguably the most spectacular 4,000-mile-long runway on the planet. “It did a lot for the globalization of Fendi,” he says of the event, which was rumored to have cost north of $10 million and featured everything from heated bench seats to cashmere shawls to protect Zhang Ziyi and Kate Bosworth, among others, from Beijing’s late-evening chill. “The payback is huge.”

A dancer at Fendi’s party in Beijing in 2007.

And how. Michael Burke, CEO of Fendi, says the Great Wall show racked up an estimated $150 million worth of media exposure. “You have to be bold, very innovative, doing things in a unique way and with extreme perfection and quality,” he says. “That’s what sets luxury fashion companies apart from the rest of the crowd…going where no one else has gone before.” That also means getting the message out to customers in fast-growing emerging markets like the Middle East, Russia and China, who are taking up the slack as purse strings tighten in the West. Notes Burke, “We have customers in the far reaches of Sichuan Province.”

The scale of events today reflects the global scope of the luxury-goods industry, which exploded in the Nineties, leaving its carriage-trade image in the dust. “It’s extreme compared to the past, but it’s not extreme if you look at the world today,” Burke says. Not so long ago, designers relied on department-store buyers and fashion editors to deliver the message about their products and trends to the final consumer. “When you can see Fendi on the Great Wall on CNN, CCTV or Good Morning America, it’s direct—there’s no filter. In the past, communication was top-down.Today, it’s more horizontal.”

Sidney Toledano, CEO of Dior, has witnessed such flat-world phenomena. He was surprised to hear friends of his 20-year-old son, Alan, tell him how much they liked Dior’s latest fashion show—especially since none of them was invited. “They talked about it as if they were there, but they saw it on the Internet,” Toledano recalls over a lunch of lobster risotto in Dior’s hushed, plush gray salons on the Avenue Montaigne.

Dior’s couturier, John Galliano, is a consummate showman who has been thinking big for years. There was his Versailles outing for the house’s 60th anniversary in July 2007; a launch party for the fragrance Dior Addict at the Lido in October 2002 that saw him enter the party, stage right, aboard a fake aircraft suspended from the ceiling; and the “Diorient Express” locomotive that steamed into the Gare d’Austerlitz loaded with high-fashion Pocahontases in July 1998. Yet Toledano insists that a house like Dior has to communicate in ways big and small—from intimate dinners for its Russian jewelry clients on their New Year’s Eve, January 12 (based on the Julian calendar used before 1918), and private visits to art exhibitions Dior sponsors to its no-holds-barred couture spectacles. Some events have more regional scope, like the 2006 opening of Dior’s Moscow flagship in Red Square—the ribbon cut by Sharon Stone—followed by a feast of beluga caviar and roasted lamb under the gilt-encrusted cupola of the Turandot restaurant. “It can be monumental or intimate,” Toledano says. “We believe that, at this level, you need direct contact between the product and consumer. What’s important is not just to make a party. You need a spin. All these people you invite have been everywhere. People need something to remember. You always have to be above expectations.”

Jewelry and watch firms have also ramped up the dazzle factor, turning product launches into theatrical productions. To shine a spotlight on two new limited-edition watches, de Grisogono hosted a three-day extravaganza in Geneva in January, peppered with performances by the Bejart Ballet Lausanne company, black-tie dinners—with the tables set on watch- movement gears—and an exhibition devoted to the seven deadly sins. Van Cleef & Arpels swung into the Royal Opera House in London late last year to unveil its Ballet Précieux collection of baubles during the Royal Ballet’s rehearsals of George Balanchine’s Jewels. And Boucheron unveiled its latest high-jewelry creations during the January couture amid contemporary artworks by Damien Hirst, Richard Prince and others on loan from French billionaire François Pinault, who controls Boucheron parent company Gucci Group.

“We are a maker of dreams; we want to incite emotions in people,” says Jean-Christophe Bedos, CEO of Boucheron. “We need one-to-one or one-to-few communication methods, experiential effects that will amaze people while helping them understand the true values of the house and that will have a lasting impact.”

To that end, Boucheron, which is marking its 150th anniversary this year, is sending its high- jewelry collection on a world tour and unveiling a series of surprising collaborations. One is with La Maison du Chocolat, which is creating a snake necklace in chocolate that Bedos notes is “enhanced with a heart-shaped, fancy brownish-yellow diamond specially cut to weigh 20.08 carats, which is worth $1 million.”

Cartier, meanwhile, has used ice to carve out its high-profile image in China, where it constructed an eight-ton version of a famous brooch owned by the Duchess of Windsor—and a full-size replica of its Rue de la Paix boutique—during the Harbin International Ice and Snow World festival. “It was phenomenal,” recalls Cartier’s globe-trotting CEO, Bernard Fornas, who is off next, with Monica Bellucci on his arm, to fete the house’s new boutique in Baku, Azerbaijan. He reckons that Cartier mounts up to 30 major events per year, between store openings; sponsorships of film festivals; exhibitions; and polo matches held on snow (Saint Moritz), sand dunes (Dubai) or with elephants in lieu of horses (Jaipur, India). Then there are the product launches, the latest of which saw 583 new high-jewelry pieces, priced from $150,000 to $28 million, unveiled at London’s Lancaster House, which was transformed into an Indian palace for one evening.

Each fete, Fornas says, “has to be the key social event in every city. You need to be very exclusive, very refined and elegant. It’s incredible PR work you have to do if you want to show the different facets of the brand.”

Of course, many of the marketing tactics pioneered by luxury fashion companies, such as using celebrities, have been adopted by industries that create countless other products, from coffee to cell phones. This means that the race is on for luxury houses to find new ways to amuse, inspire and create iconic fashion moments. “We have to make the trend,” says Fendi’s Burke. “It’s about the idea and having the professionalism and the sense of excellence to pull it off.”

Gigantic stores are the latest status symbols for some brands. You could get lost in Gucci’s new 46,000-square-foot flagship in New York’s Trump Tower, which takes designer retailing to a whole new scale, dwarfing many of its nearby competitors. And coming this fall, on Fifth Avenue at 56th Street, is a 47,000-square-foot Giorgio Armani megastore. The designer hints that a blockbuster event may mark its opening: “You will have to wait to see what we have in mind,” he says.

To be sure, the fireworks set off by the biggest players give them a formidable edge over smaller competitors, plus a leg up in emerging markets, where customers seek brands with a high recognition factor. In February an otherworldly pavilion designed by noted architect Zaha Hadid called Mobile Art, which houses artworks inspired by Chanel’s iconic quilted bags, landed in a parking garage in Hong Kong. Like a UFO, it’s next off to Tokyo, then New York and other world capitals. “To find a gallery in each city [for the exhibition], that’s boring,” says Lagerfeld. Chiquet declines to say how much the project cost, but emphasizes, “Chanel will continue to invest appropriately in ideas that intrigue, surprise and amuse our customers…. [It] reinforces its myth—surprising and provoking the public.”

Jacobs marvels that the fashion show for his signature collection has become something of a cultural event, attracting what he calls an “illustrious” audience of actresses, rock stars and artists. “You can’t send out a nice little dress to an A-list crowd,” he says. “I don’t see it stopping.”

And when Dior opened a flagship in the Landmark Mandarin Oriental Hong Kong not long ago, the French firm erected a giant screen outside and broadcast images of Galliano’s latest couture creations, which were arresting enough to stop crowds of industrious Chinese workers in their tracks. “You could see it on their faces,” Toledano says. “It was, ‘Wow.’”

Cartier: courtesy of Cartier International; Fendi: Stephane Feugere.