Faux Couture

Light-switch covers, T-shirts, hairspray—mucho mundane stuff has co-opted the moniker of fashion’s haute métier.

For anyone lucky enough to catch it on the Sundance Channel, the documentary Yves Saint Laurent: 5 Avenue Marceau 75116 Paris offers a crystal-clear window into the intensity, the sky-high level of craft, and the painstaking labor poured into a single couture creation. As he readies his spring 2002 collection, the last of his storied 40-year career, Saint Laurent holds court from a table in his atelier while his senior staffers and petites mains swirl around him. After working together for so long (decades, in some cases), Saint Laurent’s team members are expert at articulating the boss’s vision. While the clock ticks and the pressure mounts, they never lose their cool as they build each look from sketch to toile to finished garment. And as Saint Laurent heaps on the praise between drags on his ever present cigarette—there are many a “merveilleuse” and “sensationnelle” peppering the film’s soundtrack—the pride of the old-school couture makers is palpable.

Juicy Couture’s Gela Nash-Taylor (at left) and Pamela Skaist-Levy.

Somehow, viewed against this backdrop, a $48 bum-skimming number from Whore Couture—with cutouts, no less—doesn’t conjure up quite the same lofty image.

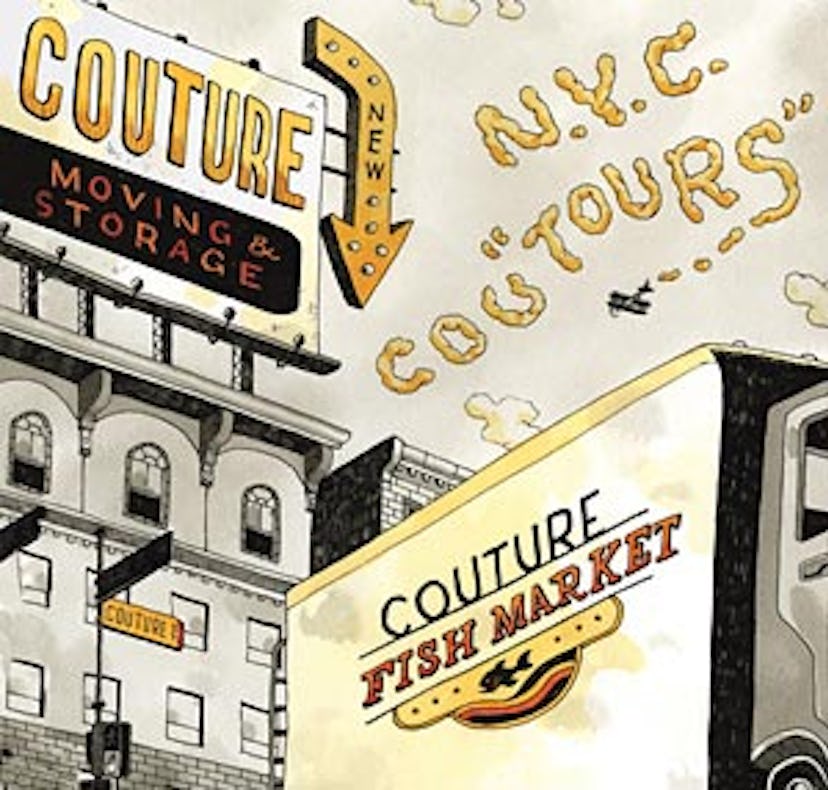

No, it’s not your imagination—the entire world has gone positively “couture” cuckoo. What started as a slow creep has become a full-on avalanche. A recent scan of trademarks issued by the United States Patent and Trademark Office revealed more than 1,000 bearing some variation on the word “couture.” And fashion is the least of it. All manner of merch is now available at the (alleged) couture level, from light- switch covers and saddle pads to rosé wine, doggie nail lacquer and hairspray. Retailers have hopped on the bandwagon too, creating special sale areas for some of their priciest (although not technically couture) duds. Even Zappos, the popular online store, has a “couture” site-within-a-site featuring high-end shoes and clothes. While it’s stocked with plenty of Jean Paul Gaultier and a smattering of Alexander McQueen, none of it is actually couture.

Although the term “haute couture” is still precisely defined by France’s Chambre Syndicale—reserved for custom-fitted clothing created by only a handful of firms meeting strict guidelines—the word “couture” itself has been utterly hijacked. When that moniker is attached to pretty much anything else, products are positioned as a cut above the herd, regardless of whether there is anything even remotely handcrafted about them.

Of course, it’s pretty easy to connect the dots between the vaunted past of the word “couture” and its decidedly alarming present; indeed, it’s hard not to blame two sunny So-Cal gals in particular. And as it turns out, Gela Nash-Taylor and Pamela Skaist-Levy are happy to take the heat. In the mid-Nineties, back when all those velour tracksuits were just a twinkle in their eyes, “couture” was still cloistered behind the gated walls of the fashion community. But after pairing it with “Juicy,” the best buds and business partners just knew they’d hit on the perfect name for their happy, cozy Cali togs. “The idea was a spoof on couture,” says Nash-Taylor. “Because we’re really the opposite of couture, which is sort of 80 hours to make one dress versus 80 hours to make 8,000 T-shirts.”

At the time, Nash-Taylor notes, “No one used that word.”

“One rep used to pronounce it ‘coater,’” adds Skaist-Levy.

Ten-plus years, massive success and one Liz Claiborne Inc. buyout later, plenty of other brands are looking to ride those “custom” coattails.

“It’s pretty amazing that ‘couture’ is now the word to add to any fashion label—even food—just to make it appealing,” says Nash-Taylor. “There’s even a bathroom line.” (She’s right: It’s the AdattoCasa Couture line of pricey leather and elaborately tiled vanities.)

“‘Couture’ is part of our modern world now, and we did start that craze,” Nash-Taylor adds. “I feel kind of proud about that.”

Not everyone finds attaching a term connoting rarefied expertise to mass-produced hoodies (or worse) quite so innocuous. Even more egregious, to some, is the inappropriate use of the term by newly minted fashion “experts.” Drop a mic into the hands of some of these red-carpet insta-pundits and you’re virtually guaranteed to hear “couture” butchered beyond recognition.

“Television commentators use ‘couture’ in the way they used to use the word ‘posh,’ as in ‘Oh, she’s wearing a couture gown.’ And I personally find that a gigantic drag,” says Simon Doonan, creative director of Barneys New York. “Nothing should be called couture unless it’s got hours of handwork in it, and blood and sweat.

“Unless 500 nuns went blind beading it,” Doonan continues, “the word ‘couture’ should not be used at all.”

Perhaps because she spent 14 years as a magazine editor before transitioning to TV six years ago, Stacy London isn’t one of the serial couture abusers, although she confesses to “giggling” at those who are. “It’s an injustice to use the term incorrectly, because couture has such a rich history,” says the What Not to Wear host. “It’s just disappointing.”

Still, London can understand why, especially on TV, the true meaning of couture has become thoroughly bastardized. “Television has democratized fashion,” she says. “To not give couture its due is a shame. But at the same time, how relevant is it in pop culture—particularly to the audiences who are watching these shows?

“Couture is nice as an art form. It’s nice as an idea,” London continues. “But it’s only people in the industry who think, Wow, I never thought of velour sweatpants as made to order.”

It’s important to note that not all of the new “couture” lines are completely plebeian. Some even carry on the handcrafted, custom-fitted tradition, albeit in a less refined fashion. Flipping through the current Morgana Femme Couture catalog, for example, one is immediately struck by the sheer number of tattoos sported by the lingerie-clad models, some of whom pose languidly against a Munsters-style hearse. But here’s the backstory: The founder of the line, 32-year-old Morgana Breadman, has been sewing since the age of six. The bulk of her work, corsetry, is completely custom.

“I do it all by hand—all the beading, lace appliqués, all that,” says Breadman. “And I consider that couture. Couture is just basically French for ‘sewing.’ That’s all it really is. But it’s also about very expensive fabrics and attention to detail. A lot of care goes into it. And it’s very time-consuming. My corsets are all done by me, by hand. So I do consider myself a couturier, in that sense.”

As such, Breadman has a bit of a bee in her bonnet when similarly named lines take the easy way out. “They might only be T-shirt makers—it’s not couture at all,” she says. “It’s just mass printing, and they slap the word ‘couture’ on the end of their name. Often I wonder if they even know what ‘couture’ means.” And if they do know, do they even care? Until another trendy fashion word appears—and “bespoke” is barreling down the tracks—there’s every chance that “couture” will suffer the same fate as that other French goodie, “champagne.”

“The problem with ‘couture’ is that if you leap to the defense of the word, people will perceive you as some horrible elitist,” says Doonan, who leaps nonetheless.

“The value of the couture comes from the fact that it preserves the notion of craft in fashion,” he says. “It’s not the fact that it’s a bunch of rich ladies hurling money at the Paris collections. And it’s not the fact that the misuse of the word is blurring the distinction between a dress from Strawberry that’s $19.99 and one that’s $40,000. I don’t care about any of that.

“Crafts are holy,” Doonan continues. “I feel exactly the same way about couture as I do [about] old hippies in Big Sur making tooled leather belts or American Indians making beautiful blankets. Exactly the same reverence should be attached [to couture]. Not because it’s posh. Not because it’s expensive. But because it’s done by hand, and it’s a dying art.”

Nash-Taylor and Skaist-Levy: Jesse Grant/Wireimage