Glenn O’Brien Could Do Everything Except Live Forever

Linda Yablonsky remembers her longtime friend, the protean writer, Style Guy, and “TV Party” host Glenn O’Brien, who died last week.

On Sunday afternoon, Glenn O’Brien lay in a rose-smothered casket at Frank Campbell Funeral Home, which has a history of sending New York’s most prominent citizens to their final rest. Friends and family seated themselves in pews facing the casket, murmuring to their neighbors as if waiting for the show begin. “Tell people to mingle?” Glenn’s widow Gina Nanni said. (Glenn was a mingler.) “I don’t want it to be so quiet.”

Indeed, there’s almost too much to say about Glenn, who has been somewhere in my life for decades, as both mentor and friend. He died last Friday, from pneumonia, at NYU Langone Hospital, just over a month past his 70th birthday, the second of March.

Nan Goldin stepped to the podium at Campbell and told everyone present to move around and talk, at Nanni’s request. Robert Aaron, a member of the old TV Party orchestra, sat at the piano on the dais and started playing—something soft, lovely. Over the next two hours, the room filled with the faces of artists, writers, actors, musicians, and thinkers whom Glenn befriended and promoted, trading memories and coming to terms with the end of a life that captured and shaped a New York that is also gone—a stark reality that did not go unnoticed.

It was like TV Party, without the drugs.

Glenn was the kind of person who made me want to live in New York, even if he did come from Cleveland. I arrived from Philadelphia a few years before he did in the ’70s, and had a whole other life, but even while living it I heard about Glenn. He was a lord of the still vibrant New York underground, a writer who caught its beat, a guy who made the scene but not just as a fixture of it. He gave it a name.

Glenn O'Brien posing in his briefs for the Rolling Stones' “Sticky Fingers” record sleeve in the Interview office in a Polaroid taken by Andy Warhol.

Right out of college, Glenn landed in the center of the social universe, Andy Warhol’s Factory. He was hired to edit Warhol’s Interview magazine for a minute before moving on to Rolling Stone and High Times, which didn’t stop him from writing “Glenn O’Brien’s Beat,” a music column for Interview that he wrote in the rhythms of New York, which had quite an influence on the music business. He discovered people. He also created TV Party, a chaotic spoof of late-night talk shows. I only saw it once. That wasn’t because it went on very late—prime time in those days—but because I lived downtown and it was broadcast on a public access cable channel that was only available uptown. In 1982, when cable came to the rest of Manhattan, TV Party went off the air. So punk.

Glenn was the E.B. White of our generation, but more fun. Where White co-authored The Elements of Style, the writer’s bible, Glenn was the original Style Guy, handing out fashion and life advice to readers of Esquire, and later GQ. He also wrote How to Be a Man for “the modern gentleman,” a book-length guide with the winking wit of an Irish poet. He launched the book between racks of suits in the Bergdorf men’s store. Afterwards, he told me that he was starting a companion volume, How to Be a Woman.

Glenn had nerve. He had wit. He had class. He had cool. He never ran short of enthusiasms or ideas, and he didn’t mince words. Ambiguity was never his thing. He went in for truth, which he made palatable—desirable, even. In the process, Glenn himself became a kind of goal.

Chris Stein and Glenn O'Brien on TV Party.

He cared about stuff—politics, poetry, art, beauty, humor, design, the life of the mind—and was as quick to voice a resentment as he was to advocate for a friend. He was the one who broke me into freelance journalism when he returned to Interview briefly, after Warhol’s death, and assigned me to interview a celebrity restaurateur. It was supposed to be one or two typed pages. I gave him 25. It was a mess. He didn’t get mad or roll his eyes. He just trimmed the piece to size and gave me another assignment. (In 2008, he returned to Brant publications for a short-lived stint as editorial director of Art in America and Interview.)

I have no idea how or when we met, but probably it was in one club or another. New York in the ’70s was all about the night. One day he was just a byline. The next he was in my life.

That was probably in the early ’80s. We had shared tastes in music, art, fashion, and books, but we actually bonded over the Sunday Times crossword puzzle. He always aced it. He’d come to my apartment alone or with a friend and we’d get high while we filled in the blanks. He talked about art and the girls who piqued his curiosity or enraged him.

Glenn O'Brien and Grace Jones after one of Konelrad's last shows at C.B.G.B.'s.

Glenn was a ladies’ man in the best sense possible—the only heterosexual man I ever knew who had as many close friendships with women as he did with men. During a brief period of sobriety in the mid-’80s, he wrote a play, Drugs, with Cookie Mueller. “We had the luxury of time on our hands, a most precious luxury,” he says in the play’s published foreword, “and one of the best ways to spend it was laughing.”

This was when AIDS was killing a lot of people we knew (including, a few years later, Cookie). It was also the moment Glenn chose for his leap into standup comedy. I remember his debut at Tramps, where he warmed up the audience for Buster Poindexter, David Johansen’s post-New York Dolls persona. I seem to recall that they sang a duet on “There Is Nothing Like a Dame,” and that whenever a joke didn’t land, Glenn shrugged it off with, “Too smart for the room.”

Thirty years later, I sometimes joined Glenn on Mark Kostabi’s weekly cable show to compete against the artist Walter Robinson or the critic Carlo McCormick to win cash for titling a Kostabi painting. Whenever I had a title that Glenn liked but that bombed with the jury, he’d turn my way and say, “Too smart for the room.”

Jean-Michel Basquiat and Glenn O'Brien on TV Party.

Glenn’s facility as a writer and ability to meet multiple deadlines a week could be intimidating. I couldn’t keep up with all the magazines he was involved with: Artforum, Purple, the in-house Bergdorf Goodman magazine, and Bald Ego, his own journal with the poet Max Blagg. This was in addition to his work as creative director of Barney’s and other commercial jobs that employed him to name perfumes or write commercials (remember Brad Pitt for Chanel?). In 2000, he landed at the Cannes Film Festival, where he debuted Downtown 81, a movie he made in 1981 with Jean-Michel Basquiat. Glenn was one of the first to recognize Basquiat’s talent. He wrote, produced, and appeared in the movie, too, directed by photographer Edo Bertoglio. Somehow the soundtrack was lost, only to be miraculously rediscovered two decades later. It’s a genuine artifact, a document of a time and a place no longer visible.

Every time I saw Glenn after that, he had a new book coming out—one of so many artist monographs, or Madonna’s Sex, which he edited, or his own books, which include the anthologies Soap Box, Like Art: Glenn O’Brien on Advertising, and Penance.

Glenn O'Brien with a robot on the roof of West Broadway.

To my knowledge, Penance is the first book ever to pull back the curtain back on a church confessional. It was based on an evening in 2012 when Glenn, who grew up Catholic and was educated by Jesuits, wore priestly robes and took the confessions of sinners who came to the Chelsea Hotel to be absolved of their sins. Hilarious! We each received a print by Richard Prince in return for letting “Father G” publish our secrets. Raised in a Jewish household, I’d never done anything like it, except maybe in therapy. Put on the spot, I couldn’t think of any sins.

“Then why are you confessing?” he asked. “Have you ever prostituted yourself?” A leading question. “Did you get f—ed in the end?” How many priests would ask that? “No,” I said. “I had to do all the work.” Other people took the whole thing more seriously, he said. They cried. They admitted wanting to murderous impulses. Glenn played the part to the hilt.

He married Nanni, his third wife, in 1999—she was a publicist at Barney’s when Glenn was a creative director—and they had a son, Oscar, now 16. He sold his house in Bridgehampton and bought a modernist manse in West Cornwall, Connecticut that had been the haunt of a famous yogi. When I’d go there for holiday weekends, Glenn would pick me up from the train in his Tesla. He loved that car. Sometimes he and Gina had other guests, usually Walter Robinson and his wife, Lisa Rosen. Occasionally, Terence, Glenn’s adult son with his first wife, would be there, too. We did country things like go for walks, tell stories, read, swim, eat, visit nearby friends, watch Glenn cook the bacon and squeeze the oranges for breakfast.

David Bowie with Glenn O'Brien, wearing a Dickies jumpsuit, at a taping of TV Party at the club Hurrah.

He’d spent a fortune remaking the house into a thing of beauty. It had room for his collections—of furniture, art, books, and records—that wouldn’t fit in his NoHo loft. There was always good music in the air, often jazz, sometimes R&B. Glenn had great taste in everything. I loved his library. He had hundreds of books. There were piles in every room (including the bathrooms) of Donald Barthelme, Jane Bowles, Iris Owens, James Baldwin, H.L. Mencken, Virgil, Homer, and so on through the centuries. He’d read everything, and could write anything—unless it was about himself.

A few years ago, he told me he had a contract to write a memoir. It would be his personal experience of the art world since Warhol. But suddenly he was blocked. He couldn’t seem to get it done.

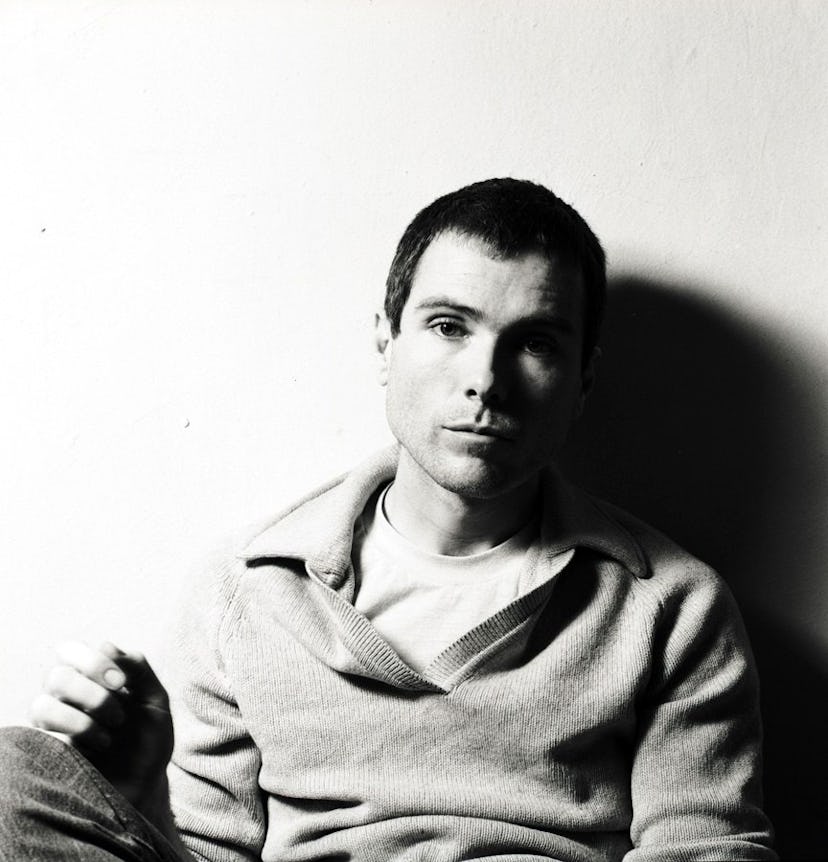

Glenn O'Brien with his “last haircut before I went nuclear.”

Last New Year’s, I drove to West Cornwall with Nan Goldin. (Glenn wrote the essay for her book, Diving for Pearls, and she appeared on his Apple TV talk show, “Tea at the Beatrice.”) Glenn was not the usual Glenn. He didn’t make breakfast. He didn’t play records. He was terribly frail, weakened by treatments for a cancerous spine. He didn’t try to to hide how frightened he was of dying. “I love you,” he said, repeatedly, to every friend who came near. Back in New York, in the succeeding months, many—a great many—did. The other day, Lisa Rosen recalled a line from “Epitah,” a poem by Merritt Malloy that was a favorite of Glenn’s.

Love doesn’t die,

People do.

So when all that’s left of me,

Is love,

Give me away.

What greater gift could there be? Read his books. In them is the Glenn I knew, the Glenn who could do anything—except live forever.

That’s what happens when you’re too smart for the room.

Glenn O'Brien as Le Roi in Paris, photographed by Jean-Baptiste Mondino.