Kazuyo Sejima: The Closet Starchitect

She has designed icons and won the Pritzker, and is curating this fall’s Venice Architecture Biennale. So why don’t you know her name?

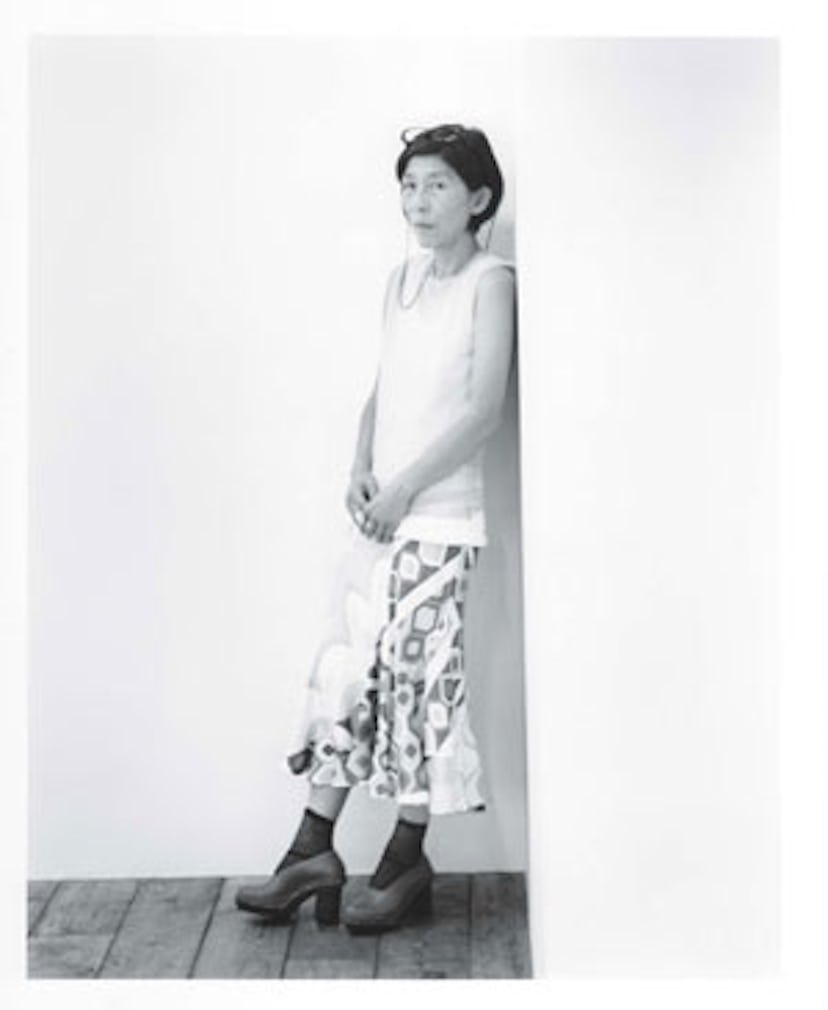

Analytic and poetic, assertive and recessive, Kazuyo Sejima is the moonwalker of architecture, gliding in opposite directions with mind-bending grace. In 2004 the Tokyo-based firm SANAA, which she and Ryue Nishizawa had formed less than a decade earlier, catapulted onto the world scene with the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, in Kanazawa, a city on the Sea of Japan. Winning the Golden Lion at that year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, the museum placed SANAA and Kanazawa on the map of contemporary culture. As SANAA went on to complete increasingly prestigious commissions, including the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York, Sejima herself remained as hard to pin down as her architecture. In both her buildings and her manner, she is the opposite of that other prominent female architect, Zaha Hadid. Sejima dresses, speaks, and works in a way that deliberately deflects attention.

So it is with ambivalence that Sejima has responded to a year that thrust her into the spotlight. In the spring she and Nishizawa were awarded architecture’s highest honor, the Pritzker Prize. They also saw the inauguration of the Rolex Learning Center, a library and student complex in Lausanne, Switzerland, that happens to be their most audaciously attention-grabbing building to date. And this fall Sejima—on her own—is curating the 12th Venice Architecture Biennale. When she was offered the position, Sejima responded typically by asking if she and Nishizawa could be codirectors. Informed that under the rules there could be just one, she agreed to take the position, and then promptly enlisted Nishizawa as her adviser, along with Yuko Hasegawa, the former chief curator of the Kanazawa museum.

In recent years the Biennale has been curated by critics and scholars rather than by practicing architects. When I asked why Sejima was selected, Biennale president Paolo Baratta emphasized that an architecture exposition, unlike an art show, cannot display its actual subject matter, and an offering of models, renderings, and plans is redundant in a media-saturated culture. He hopes this Biennale, which opens August 29, will be viscerally powerful for visitors. “The exhibition is to make you have the experience of architecture, using the language of emotion more than of rational explanation,” Baratta told me. That impulse led him to Sejima. “Sejima is really the architect who refuses to conceive architecture as a way of representing the power of somebody, or the money of somebody else, or the ambitions of the client,” he said. “She instead comes back to an idea of architecture where functions, relations, and the division of space are what matters.” Her pared-down architecture is so functional, it’s lyrical.

Sejima made a brief visit to New York in late June to discuss the design of a Derek Lam boutique on Madison Avenue that is scheduled to open in October. Lam’s clothing, like Sejima’s own extensive collection of Comme des Garçons pieces, features a combination of intelligence, detailing, and understatement that appeals to her. She fashioned a store to match. Divided by 12-foot-tall curved acrylic panels that set boundaries for the clothes without diminishing them, the shop exemplifies the qualities Baratta described. “Very often, if an architect makes a place minimal and functional, it is very cold and inhuman,” Jan Schlottmann, the company’s CEO, said. “Or other architects can make a place that is lush and luxurious, and then it becomes very charged and overshadows the product. Nishizawa-san and Sejima-san make the product look even better, but it’s very human and warm. They create a house for it.”

While in New York, Sejima, who will turn 54 in October, discussed her work on the Biennale with me. (Having just come off a tobacco-deprived flight from Tokyo, she would occasionally dart outside for a quick cigarette.) Along with architects, she invited artists and engineers who work with the fundamental elements of light, sound, and water, and she allocated each participant an individual space—in either the ancient, cavernous Arsenale or the late-19th-century Palazzo delle Esposizioni—to design and control. “She gave us complete freedom to do anything, but I understand that freedom has to be directed,” Spanish architect Antón García-Abril told me. During their initial meeting Sejima said to García-Abril, whose architecture is characterized by large, forceful forms: “Why don’t you break the scale of the space? Why don’t you insert some of your big elements inside?” Happy with the suggestion, he designed an installation of two 65-foot beams, one balanced on top of the other, and both at a diagonal to the columned, longitudinal space of the Arsenale. Sam Chermayeff, the SANAA architect managing Venice, said his boss had carefully plotted the rhythm of the visitor’s experience. “Sejima sees it very intuitively: dense, open, light; heavy, open, dark. She orders it that way, almost as if she were squinting.”

The first display in the Arsenale is a 12-ton boulder that was shipped to Venice by Chilean architect Smiljan Radic. Like García-Abril’s beams, it had to dominate the space in order to succeed. “We made a 1:1 model out of cardboard and garbage bags, to make sure it was big enough to hold the room,” Chermayeff said. While virtually every architect relies on models, at SANAA they are generated in almost ludicrous profusion. (For the Kanazawa museum, more than a thousand were fabricated.) Beginning with a lucid two-dimensional plan, SANAA uses small models to explore multiple possibilities and refinements; as the choices narrow, the remaining alternatives are mocked up in increasingly large scale. The models allow Sejima to determine whether her hunches, once materialized, will comfortably house the human body. Model building is the practical way in which her signature contradiction between mind and body is resolved. “Her thought about the physicality of the body is very abstract,” says architect Toyo Ito, in whose office Sejima apprenticed for six years. “Usually, when you become too detached, it is too much. But because of her physicality, the architecture is also comfortable. When you visit a place, you feel something. It is not just an abstract object.”

In a conversation several years ago, Ito recalled that as a young architect, Sejima “cried a lot. There was a time we had a group meeting in the morning, and I criticized her in front of everybody. She came to me afterward and said, ‘You didn’t have to do that,’ and there were tears in her eyes.” Female architects were extremely rare in Japan at the time; they are still not the norm. Unlike many successful women, whose personalities show the strain of achieving prominence in a male-dominated culture, Sejima is unhistrionic, empathetic, and warmly gracious. Perhaps it is a tribute to her parentage: Her mother (whose aristocratic family once owned an important castle) is well educated; and her father, an engineer, had an unusually enlightened attitude for a Japanese man of his time. “My name is Kazuyo, and normally, a girl has a name ending in ‘ko,’” Sejima once told me. “‘Yo’ is a little bit different. My mother said my father gave me that name because he wanted me to make my own way.” At the office in Tokyo, she is acutely sensitive to her colleagues, most of all to Nishizawa, who is 10 years her junior and easily overshadowed by her charismatic persona. (It is telling that in the firm’s name, which stands for “Sejima And Nishizawa And Associates,” the conjunctions are capitalized along with the proper names; the relation between the personalities are as important as the people themselves.)

Although their complementary natures can be exaggerated, making Sejima seem all right brain to Nishizawa’s left, it’s true that her responses are usually intuitive and his are expressed in rational terms. “During the discussions about Lausanne, I explained how to generate structural geometry,” their frequent collaborator, engineer Mutsuro Sasaki, told me at the time of the schematic design phase of the Rolex Learning Center. “Nishizawa always tries to understand it logically. Sejima’s comment is, ‘This point could be higher, and then I would be happy.’” The architects began with the simple premise of wanting to place the entrance to their very large building in the center so that any point inside could be reached without an oppressively long walk. They had originally conceived a large, thin, flat slab over an open space with very few support columns. “I rejected it as nonsense,” Sasaki said. To resist deflection forces, the roof would have to be ridiculously thick—more than one story. Instead, he proposed a gently curving roof that would minimize bending stress. By maintaining a constant height between the parallel floor and the roof, the scheme would create interesting congregation spaces beneath the swoops. “Because of this proposal, Sejima started to think of a new kind of structure,” Sasaki said. “If there is a formalist curve proposed, she would reject it. She will never turn out to do Frank Gehry’s buildings.” The initial motive was functional; then she refined it, to make it beautiful.

Critics tend to stereotype SANAA as working only in white or glass, but Sejima chafes at such limitations. I was with her and Nishizawa five years ago in Ohio, as their first American building, the Toledo Museum of Art’s Glass Pavilion, awaited installation of the glass facade. “I think she loves glass, but she says she doesn’t like glass,” Nishizawa joked. To which Sejima replied, “Not don’t like, but not so interesting.” A couple of months later in New York, she said to me, “White I don’t like so much now. That doesn’t mean I like color. Just natural is also uncomfortable for me. So I am trying to find a type of new space, but I cannot do it.”

With the design of the Rolex Learning Center and the masterminding of the experiential Venice Architecture Biennale, Sejima has come closer to her asymptotic goal of a pure architecture, one that uses material to create the immaterial, that is both grounded and elevating. She is trying for an architecture that will be inhabited, rather than merely appreciated from the outside. Think of it as clothing—not an outfit that you admire on another person or that you check out on yourself in the mirror, but something that, when you are wearing it, makes you feel better and more like yourself.