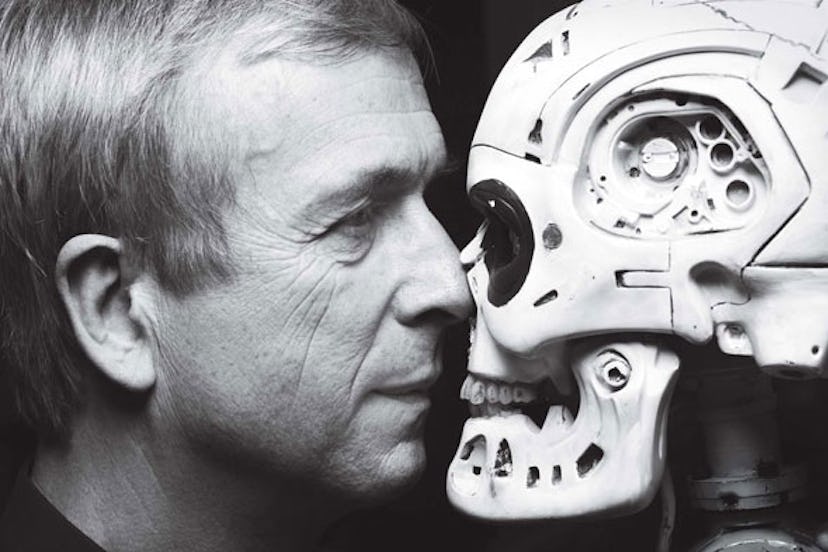

Kevin Warwick, a 56-year-old Brit, doesn’t look like your typical cyborg. Forget Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Terminator—the University of Reading’s professor of cybernetics more closely resembles, well, a university professor. But as any sci-fi writer will tell you, within every ordinary Joe there’s a robot bent on world domination.

Twelve years ago, Warwick declared he was on a mission to become the world’s first man-turned-machine. He began this undertaking, dubbed Project Cyborg, in 1998, when he had a microchip embedded in his body, something that had never been attempted before. Surgeons inserted a glass capsule containing several micro- processors into Warwick’s arm, and for the next nine days his presence was recorded by computers throughout the university’s cybernetics department. “The implant responded to computer signals,” Warwick explains in his cramped and chaotic study. “Doors opened automatically, lights turned on when I entered a room, and my PC announced ‘Hello, Professor Warwick’ when I approached. At the time newspapers were reporting that it had run the bath and chilled the wine for me, which sounds awfully nice but sadly wasn’t true. However, it could have done anything had we programmed it accordingly. It could have launched missiles.”

In 2002 Warwick moved on to phase two. A more sophisticated operation placed microchip implants onto his and his wife’s nervous systems, linking them to a nearby computer—and to each other. Using the technology, Warwick was able to control a robotic hand as well as an electric wheelchair (another goal was to record his and his wife’s sensory experiences, such as pain and pleasure). Warwick was even eager to record sex with his wife (although he won’t say if this actually happened), “the idea being, we’re interconnected, so we’ll each feel what we’re doing to the other,” he says. “The possibilities are mind-blowing!”

Going forward he hopes to include others in these sorts of experiences. An outcome of the project, he says, might be that he and his fellow implantees will evolve into a cyborg community hooked up “via their chip implants to superintelligent machines, creating, in effect, superhumans.”

From Project Cyborg’s earliest days, Warwick’s motives have been scrutinized. Was this unassuming Brit pioneering something that would save or destroy mankind? Would he use his knowledge to make possible the sort of monsters that hitherto had been the stuff of B movies? Warwick says his motivation is two-pronged. His discoveries are being developed with a view to creating electronic procedures to combat Parkinson’s disease, blindness, arthritis, and schizophrenia. “Electronic—as opposed to chemical—medicine may well become the norm,” he says. “Taking Advil for a headache numbs the whole body, whereas electronic remedies could treat only the specific area.”

Still, he’s not just interested in healing the sick. Warwick hopes the technology he’s developing will upgrade man’s capacity to do pretty much anything. “Being linked to another person’s nervous system opens up a whole world of possibilities,” he muses. “Thought communication instead of cell phones, for example. And as for anatomical enhancement…”

One thing is certain: Warwick’s media-friendly, sky’s-the-limit approach to cybernetics has made him an influential figure. Although skeptics claim that Project Cyborg is more about self-promotion than pioneering science, it remains a case study for science classes at Harvard, Stanford, and MIT. Some of the world’s most innovative creative voices have seen potential in his work too. Both Stanley Kubrick (for his uncompleted A.I.) and David Cronenberg (while making the 1999 film eXistenZ) were influenced by Warwick’s fusion of man with machine; and Chris Cunningham’s sublime 1999 video for Björk’s track All Is Full of Love was a wink to the professor’s cybernetic explorations—it featured two cyborgs passionately embracing. In the realm of fashion, Hussein Chalayan acknowledged cyborg technology during his memorable spring-summer 2007 show, in which six robotic dresses reconfigured themselves of their own accord using embedded technology and smart wires.

Only time will tell if Warwick’s vision of a cyborg community will become a reality. In the meantime, he is about to unveil his most advanced specimen to date: a robot that will be operated by an implanted human brain grown from neurons. “It’ll end up having about 30 million brain cells, and will be able to teach itself new skills every day,” he maintains. He’s also initiating the third phase of Project Cyborg, which involves embedding a more elaborate chip directly into his brain. “In my lifetime,” he concludes, “the things I’m researching will definitely end up becoming commercial products. I’m half expecting Steve Jobs to call up tomorrow to discuss developing cell phones or computers within the brain. It’s only a matter of time.”