All the World’s His Stage

“I have always said there is not one art world,” says Okwui Enwezor, the Nigerian-born director of the 56th Venice Biennale. “I’m interested in going beyond the rigidity of what is supposed to be good or accomplished work and what is supposed to be bad or unsophisticated work. I want to assess the complexity of these multiple worlds.” Known for looking at accepted realities in new ways and for pushing African and diaspora artists to the foreground, Enwezor, 51, has proved himself one of the most ambitious curators of his generation. Opening in May, his biennale exhibition, “All the World’s Futures,” promises to be “a raucous gathering,” as he calls it, one that willinventively connect the festival’s two sprawling sites on the island. Punctuated by artists’ projects, the show will spill out from the Arsenale, a centuries-old shipyard, through a once-derelict garden and onto the grounds of the Giardini, the park where participating countries showcase their artists in national pavilions.

Redrawing the global art map and seeing art as a barometer of the state of things has been Enwezor’s curatorial vision from the start. “We’re looking at the changes in the life cycles of many countries in that park,” he says of the Giardini, which he’s envisioningas a kind of garden of disorder. “The first Russian pavilion, in 1914, was Russia. Then it was the Soviet Union, and then back again to being Russia, so we’ve seen the making and unmaking of worlds there.” Expect topical ruminations on man’s expulsion from

Eden in the wake of war and ecological disaster, live performances, and spoken and sung verse from artists like Jason Moran and Jeremy Deller. For a program overseen by the director Isaac Julien, Karl Marx’s Das Kapital will be read aloud daily in the Italian pavilion in an arena designed by the British-Ghanaian architect David Adjaye.

Enwezor’s route to the coveted directorship of the biennale has been an unlikely one. He began his career as a poet after moving from Nigeria to the Bronx at age 18 to earn a degree in political science from Jersey City State College in New Jersey. In the mid-’90s, he founded a hip African arts magazine in Brooklyn and was soon attracting notice from museums; his breakthrough as a curator came in 1996 with “In/sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present,” a landmark exhibition of 30 artists at the Guggenheim in New York. The show was one of the first to put contemporary art from post-independence Africa front and center. Currently the director of Munich’s Haus der Kunst museum, he has won international acclaim for the many giant survey exhibitions he has helmed, among them the prestigious “Documenta 11” in Kassel, Germany, in 2002; the Gwangju Biennale in South Korea in 2008; and the Triennale d’Art Contemporain of Paris at the Palais de Tokyo in 2012.

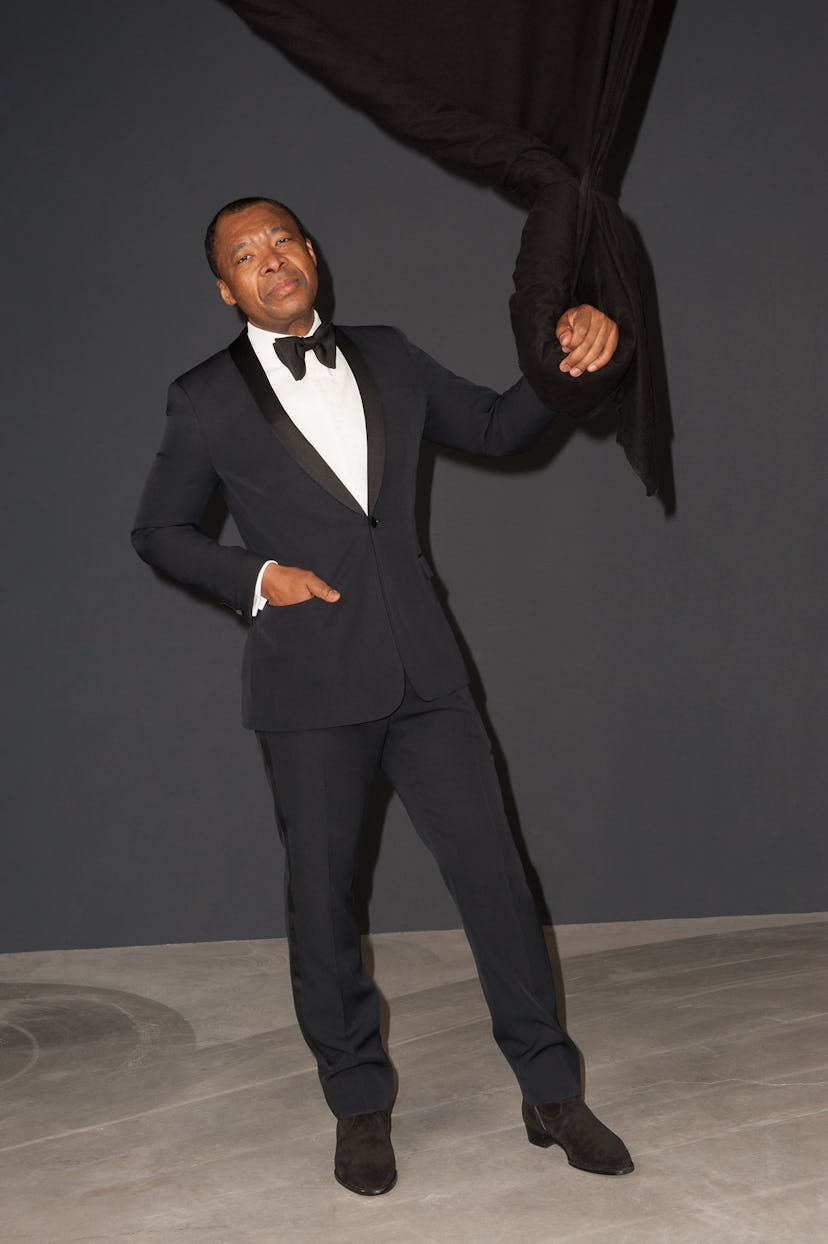

For all his erudition, the tall, elegant Enwezor is equally admired for his sartorial savoir faire. Not for him the stripped-down black uniform of his peers: He prefers bespoke double-breasted suits from Savile Row’s Kilgour, pocket squares, and knotted cravats. “There’s a kind of male dressing culture he’s in love with that’s slightly old-fashioned,” says Adjaye. “He’s not a fashionista. He’s someone who is very aware of the power of dress and of being yourself in the world.” Enwezor claims his mother’s style as a touchstone. Growing up in Nigeria, he was educated at a colonial British-style boarding school, where, he recalls with distaste, “They taught you all these mannerisms, and you were not allowed to use the local indigenous language. You were punished if you were caught not speaking in English. It was a bit weird.” But in his mother’s approach to dressing, he found a celebration of North African and Nigerian culture. “She had an amazing wardrobe and had all kinds of fabrics woven for her. Nigerian fashion is very individual. People style themselves. The way you tie your headdress is not supposed to look like anybody else’s.” Interested in her family “looking proper,” he says, she didn’t shop in boutiques but had clothing custom-made by a tailor. “It was always a great thing come holiday time, when you would go have new suits and shirts made,” he says. The first fashion fad he fell for was the safari suit. Then, in the early ’80s, he became taken with Billy Dee Williams in his white-collar shirt–and–tie uniform. Miles Davis has had a more lasting impact as a style icon, “not just for his power as a musician but for his renegade spirit, his posture of absolute refusal,” Enwezor says.

During the biennale, he plans to wear his Saint Laurent brushed suede boots or Nike sneakers by day and boots from the Chanel-owned Massaro for soirees. Adjaye, who, like Enwezor, travels constantly, calls his longtime friend “the consummate options traveler.” In other words, he checks his bags. “I pack too much,” Enwezor sheepishly admits. “I bring too many shoes.”

Photos: All the World’s His Stage

Enwezor wears Saint Laurent by Hedi Slimane jacket, $2,850, and trousers, $1,090, Saint Laurent, New York, 212.980.2970; Tom Ford bow tie, $250, 888.TOM.FORD; Spencer Hart shirt, spencerhart.com; Massaro boots, $1,375, Massaro, Paris, 33.01.44.50.68.68.

Wangechi Mutu’s Nyanya Nyoka, 2014, and Nguva (video), 2013. Courtesy of the Artist, Victoria Miro Gallery, and Gladstone Gallery.

Huma Bhabha’s Untitled, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94.

Charles Gaines’s Walnut Tree Orchard: Set 13, 1975–2014. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York/Photo by Steven Probert.

Jeremy Deller’s Jukebox, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York.

Chris Ofili’s Annunciation, 2006. Photo by Maris Hutchinson/EPW/Courtesy of David Zwirner.

Hans Haacke’s Gift Horse, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

Fashion assistant: Raffaele Avella. grooming by Annamaria Abbate at Closeup Milan.