Adaptation

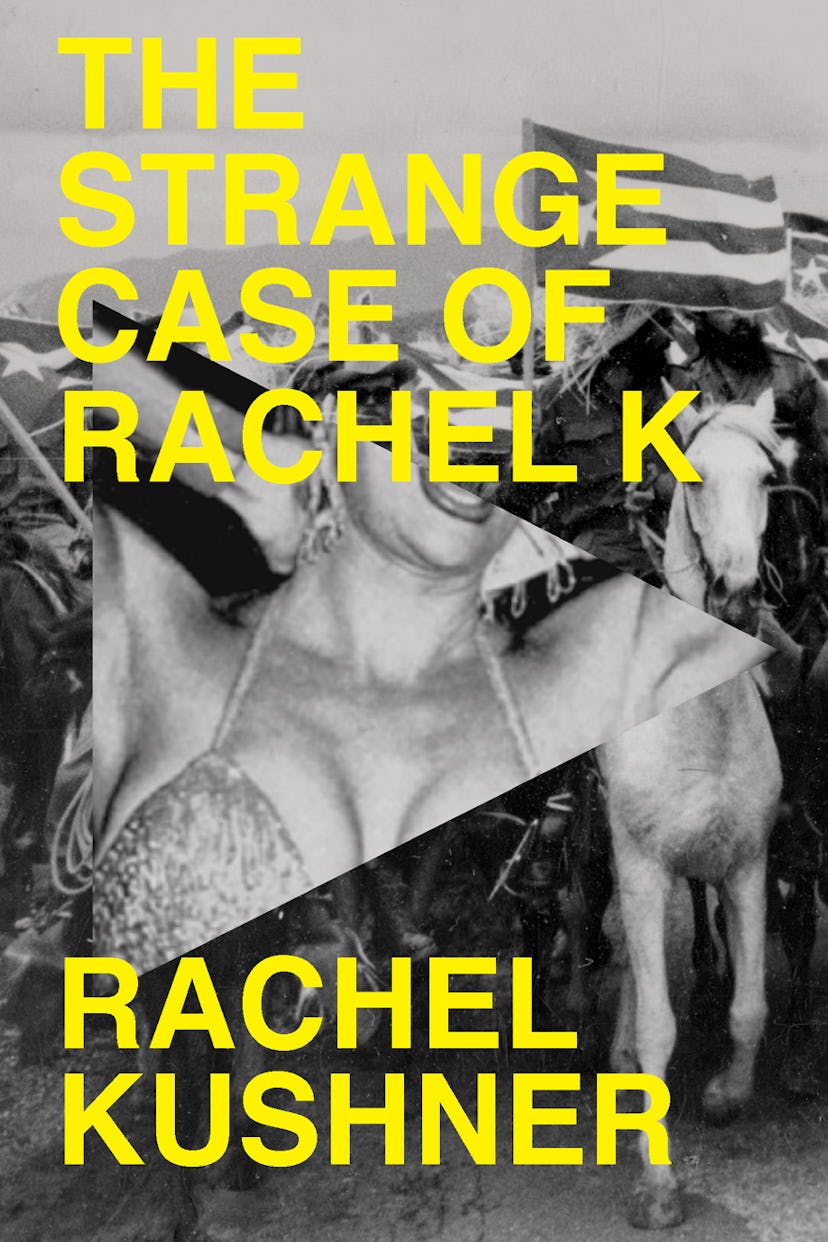

Rachel Kushner’s 2013 novel The Flamethrowers received some rapturous acclaim, but one dissenting opinion, by the poet Frederick Seidel in the New York Review of Books, complained that the story of Reno, an artist navigating New York’s downtown art world in the ’70s, seemed overly “interested in being made into a movie.” (In fact, there have been rumors of a film adaptation, and Kushner was recently named guest director of the Telluride Film Festival in September.) Her new book, a slim volume in three parts called The Strange Case of Rachel K, is no less cinematic; it takes its title and its setting from an obscure ’70s Cuban film that happens to share a name with the author. In the prologue, Kushner notes that although she’s never seen it, the film helped inspire her first novel, 2008’s Telex From Cuba, to which Rachel K exists as a kind of prequel. Many of the characters in Rachel K dabble in experimental filmmaking, and Kushner follows suit in a way, forsaking the clear narrative drive of her two previous books for something more abstract, clipped, and symbolic. So, yes, Rachel K might also be interested in being a movie, more specifically, in the ways that fiction might be able to harness the surreal qualities of cinema.

Just as Flamethrowers unfolds in a series of run-ins and accidents, Rachel K maps how coincidence can propel a narrative. Kushner tracks the velocity of the uncanny in these tales of seafarers, cartographers, broadcasters, and dancers—various seekers trying to get somewhere, even if, as she writes, “everyone here was lost.”

The first story reimagines the discovery of Cuba as a creation myth; the new map is eventually lost to time, described much like faded film stock, “lingering only as faint unglimpsable residues.”. Another story tells of an affair between an émigré and a Havana local, who come together as filmmakers. And the final tale follows the titular Rachel K., an exotic dancer at the Cabaret Tokio’s Pam-Pam Room: Alone in her dressing room, she would press her cheek against the wall, looking sidelong into her mirror, hoping to see whatever secrets mirrors seem to hide. “If she knew the mirror’s secret, she’d know how to pass to the other side,” Kushner writes. It brings to mind the oft-quoted line by the filmmaker Jean Cocteau, who directed 1950’s Orpheus: “I do not narrate the passing through of mirrors; I show it, and in some manner, I prove it.” Cocteau’s point was that because he always showed something rather than explained it, its existence was indisputable. And perhaps Kushner, in her way, shows her characters, past and present, have passed a similar test.