Thanks to Stem Cell Therapy, Thinning Hair May Be a Thing of the Past

In a desperate quest to save her sparse strands, Sandra Ballentine stumbles upon a potential hair growth miracle.

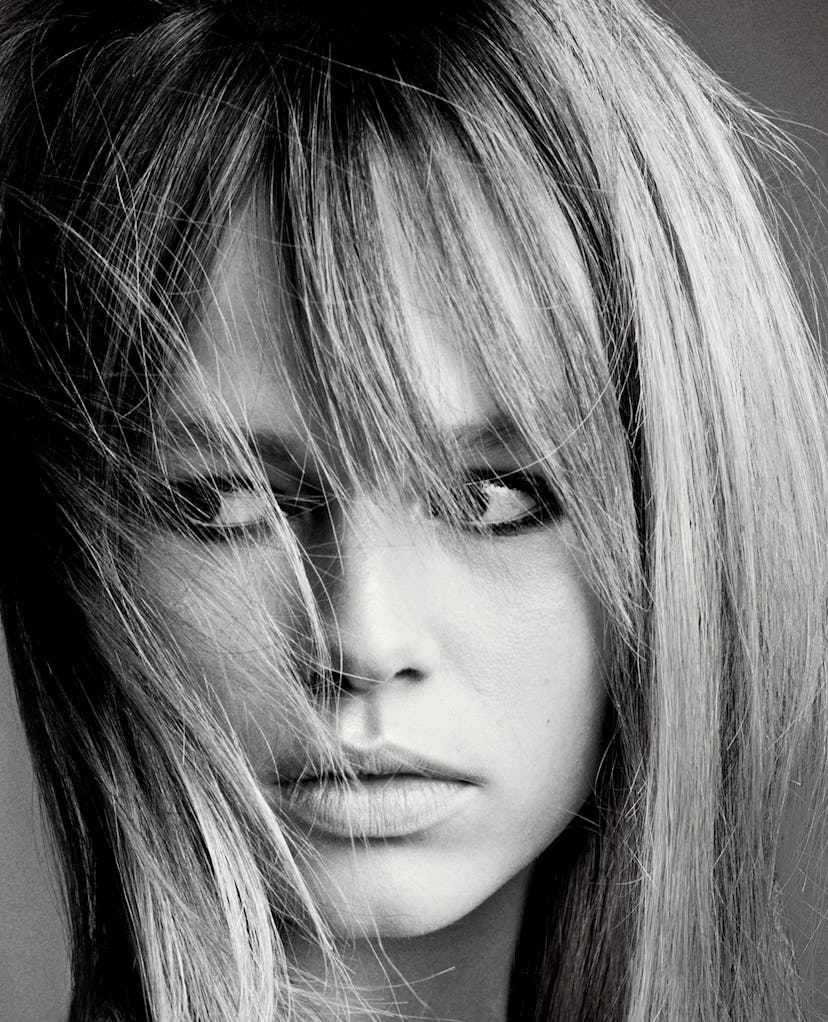

Call me a creature of habit, or just plain boring, but I’ve been wearing my hair long, blonde, straight, and side-parted for more than 15 years. The only thing that’s really changed is how much of it I have left. Whether the result of bleach, blowouts, stress, hormones, genetics, or all of the above, I’ve been shedding like a cheap angora sweater since the age of 30. And, to make matters worse, the hair I do have is fine, fragile, and flyaway.

It wasn’t always so. Flipping through old photo albums, I found evidence not only of my natural color (a long-forgotten brown) but also of the graphic, blunt bob I sported in my early 20s. I had oodles of hair back then and would smooth it to my head with pomade and push it behind my ears—much like Guido Palau did on some of the models in Prada’s spring runway show, I noted smugly.

Efforts in the ensuing years to save my ever-sparser strands have been all but futile. You name it, I’ve tried it: platelet-rich plasma (PRP), treatments in which your own blood is spun down to platelets and injected into your scalp; mesotherapy (painful vitamin shots, also in the scalp); oral supplements; acupuncture; massage; herbal remedies; and high-tech hair products. I’ve even resorted to wearing a silly-looking helmet that bathed my head in low-level laser light and was said to stimulate failing follicles. At this point, I would soak my mane in mare’s milk under the glow of a waxing supermoon if I thought it would help.

Since hair regeneration is one of the cosmetics-research world’s holiest grails (read: potential multibillion-dollar industry), I’ve always hoped that a bona fide breakthrough was around the corner, and prayed it would arrive well ahead of my dotage. As it turns out, it might actually be a five-hour flight from New York—and around $10,000—away.

It was the celebrity hairstylist Sally Hershberger who whispered the name Roberta F. Shapiro into my ear. “You have to call her,” she said. “She is on to something, and it could be big.” Shapiro, a well-respected Manhattan pain-management specialist, treats mostly chronic and acute musculoskeletal and myofascial conditions, like disc disease and degeneration, pinched nerves, meniscal tears, and post–Lyme disease pain syndromes. Her patient list reads like a who’s who of the city’s power (and pain-afflicted) elite, and her practice is so busy, she could barely find time to speak with me. According to Shapiro, a possible cure for hair loss was never on her agenda.

But that’s exactly what she thinks she may have stumbled upon in the course of her work with stem cell therapy. About eight years ago, she started noticing a commonality among many of her patients—evidence of autoimmune disease with inflammatory components. Frustrated that she was merely palliating their discomfort and not addressing the underlying problems, Shapiro began to look beyond traditional treatments and drug protocols to the potential healing and regenerative benefits of stem cells—specifically, umbilical cord–derived mesenchymal stem cells, which, despite being different from the controversial embryonic stem cells, are used in the U.S. only for research purposes. After extensive vetting, she began bringing patients to the Stem Cell Institute, in Panama City, Panama, which she considers the most sophisticated, safe, and aboveboard facility of its kind. “It’s not a spa, or a feel-good, instant-fix kind of place, nor is it one of those bogus medical-tourism spots,” she says. Lori Kanter Tritsch, a 55-year-old New York architect (and the longtime partner of Estée Lauder Executive Chairman William Lauder) is a believer. She accompanied Shapiro to Panama for relief from what had become debilitating neck pain caused by disc bulges and stenosis from arthritis, and agreed to participate in this story only because she believes in the importance of a wider conversation about stem cells. “If it works for hair rejuvenation, or other cosmetic purposes, great, but that was not at all my primary goal in having the treatment,” Kanter Tritsch said.

While at the Stem Cell Institute, Kanter Tritsch had around 100 million stem cells administered intravenously (a five-minute process) and six intramuscular injections of umbilical cord stem cell–derived growth factor (not to be confused with growth hormone, which has been linked to cancer). In the next three months, she experienced increased mobility in her neck, was able to walk better, and could sleep through the night. She also lost a substantial amount of weight (possibly due to the anti-inflammatory effect of the stem cells), and her skin looked great. Not to mention, her previously thinning hair nearly doubled in volume.

As Shapiro explains it, the process of hair loss is twofold. The first factor is decreased blood supply to hair follicles, or ischemia, which causes a slow decrease in their function. This can come from aging, genetics, or autoimmune disease. The second is inflammation. “One of the reasons I think mesenchymal stem cells are working to regenerate hair is that stem cell infiltration causes angiogenesis, which is a fancy name for regrowing blood vessels, or in this case, revascularizing the hair follicles,” Shapiro notes. Beyond that, she says, the cells have a very strong anti-inflammatory effect.

For clinical studies she’s conducting in Panama, Shapiro will employ her proprietary technique of “microfracturing,” or injecting the stem cells directly into the scalp. She thinks this unique delivery method will set her procedure apart. But, she cautions, “this is a growing science, and we are only at the very beginning. PRP is like bathwater compared with amniotic- or placenta-derived growth factor, or better yet, umbilical cord–derived stem cells.”

Realizing that not everyone has the money or inclination to fly to Panama for a treatment that might not live up to their expectations, Hershberger and Shapiro are in the process of developing Platinum Clinical, a line of hair products containing growth factor harvested from amniotic fluid and placenta. (Shapiro stresses that these are donated remnants of a live birth that would otherwise be discarded.) The products will be available later this year at Hershberger’s salons.

With follicular salvation potentially within reach, I wondered if it might be time to revisit the blunt bob of my youth. I call Palau, and inquire about that sleek 1920s ’do he created for Prada. “Fine hair can actually work better for a style like this,” he says. “In fact, designers often prefer models with fine hair, so the hairstyle doesn’t overpower the clothing.” Then he confides, “Sometimes, if a girl has too much hair, we secretly braid it away.” Say what? “I know, it’s the exact opposite of what women want in the real world. But models are starting to realize that fine hair can be an asset. Look, at some point you have to embrace what you have and work with it.” Wise words, perhaps, and proof that, like pretty much everything else, thick hair is wasted on the young.

From the Minimalist to the Bold, the 5 Best Hair Trends of New York Fashion Week

Models at Tory Burch wore low ponytails, embellished with an oversized black bow.

Models at Alexander Wang sported a sleek grungier look with their wet locks in naturally tousled waves.

Models at Proenza Schouler embraced their natural hair textures, wearing their locks in sleek, minimalist styles.

Brandon Maxwell’s Fall 2017 show was all about boldness, so models wore their hair in voluminous curls.

Altuzarra brought back the embellished headband in various colors of red, black, maroon and brown.

Watch W’s most popular videos here: