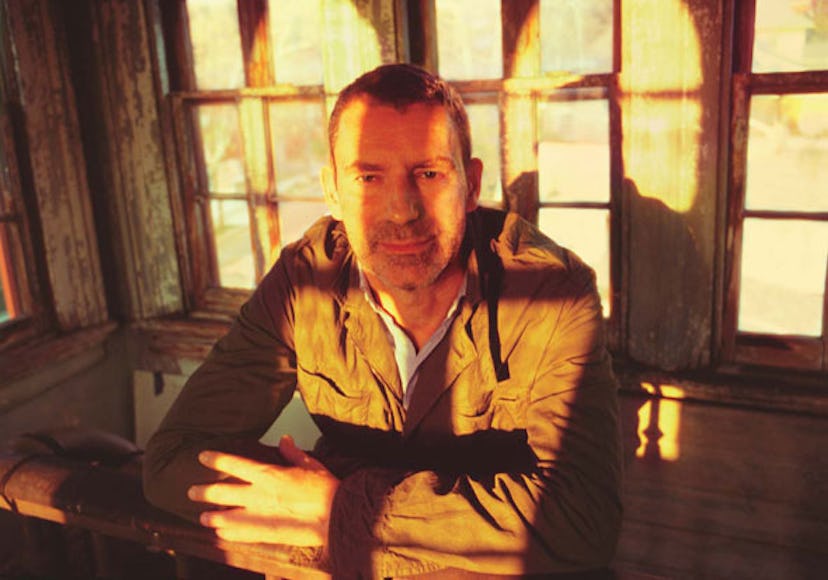

Lens Man: Tomas Maier

After reinvigorating Bottega Veneta, Tomas Maier is turning the company’s ads into fine-photography showcases.

“I feel like I should be doing coke in the bathroom!” Robert Longo is standing in front of a bulletin board plastered with printouts of his “Men in the Cities” series, the early-Eighties graphite drawings based on his black and white photographs of various friends, including Cindy Sherman, each dressed in crisp button-downs and writhing and leaping in midair. Longo pushes his black frame glasses up on his nose and bangs a fist on the pictures as Mick Jagger snarls “Under My Thumb” over the stereo system. A model skims by and shakes her hips to the music. Longo grins. “Isn’t this awesome?” he shouts.

It’s hard to blame him for indulging in some recreational déjà vu—days spent running wild in New York with such fellow artists as Sherman, Charles Clough, David Salle and Jack Goldstein—although such reminiscing is for a distinctly unbohemian, and very commercial, purpose: Longo is inside a cavernous Chelsea photo studio shooting the fall 2010 Bottega Veneta campaign under the exacting eye of creative director Tomas Maier, himself employed by the multinational Gucci Group, which in turn is owned by PPR. The advertising campaign is a first for Longo, who conceived an album cover for the Replacements and directed a video for R.E.M. and the Keanu Reeves film Johnny Mnemonic. But ever since Apple launched its iPod ads featuring silhouetted hipsters jumping around, he has felt a twinge of envy (mixed, he admits, with irritation) toward what he sees as the appropriation of his seminal Eighties work. Maier, as it turns out, had long admired the artist’s “Cities” images, and so earlier this year, he had an agent reach out to Longo about shooting Bottega’s fall pieces, which Maier describes as “very graphic” and inspired by “strong women.” “He said something to the effect of ‘Instead of ripping you off, we want to hire you,’” Longo says. “They got me at hello.”

An image from the fall 2010 campaign, photographed by Robert Longo.

Maier seems to have that effect on photographers. Since arriving at Bottega Veneta in 2001, after stints at Hermès and Sonia Rykiel, he has spun the once flagging, overlicensed accessories company into luxury gold: a restrained, trend-free lineup of clothes, bags, shoes and jewelry that last year raked in $495 million in sales. A serious student of photography and design (his father was a successful architect in his native Germany, and as a fashion student at Ecole de la Chambre Syndicale in Paris, Maier trolled local auctions for pieces to buy on the cheap), he shrewdly began trading on his commercial success for more personal projects, namely, hiring fine-art photographers, many whose work he collects, to shoot the company’s campaigns. Among those Maier has engaged are Sam Taylor-Wood, Nan Goldin, Lord Snowdon and Larry Sultan. Sultan’s spring 2009 Bottega campaign shots were some of his last before his death from cancer last December. In an industry that has typically relied on a small cadre of fashion photographers to handle multimillion-dollar advertising projects, the use of, say, Tina Barney (spring 2007) and Philip-Lorca diCorcia (fall 2005) was considered risky, not to mention provocative.

Maier is characteristically blunt on the charge that he likes to push boundaries. “It wasn’t supposed to be edgy,” he says of his decision to alternate photographers each season, using ones untested in fashion (his first try was with still-life photographer Robin Broadbent, for fall 2002). It’s a few weeks after the Longo shoot, and we’re having breakfast in midtown Manhattan. Maier, who is 53 and fond of wearing yellow tinted glasses, gets up by six most mornings, is punctual down to the minute, and, although his English is not perfect, wastes few words to make a point. “I’m sure people thought it was weird,” he says. “We’re so far in the road that it makes sense now. I think it’s so right for the company as well.”

Unlike some designers, Maier is disinterested in mining the meaning of a hem, or waxing on about the varied inspirations for a line of wallets. Everything he puts on the runway will be sold in stores (“I find for a woman nothing is more frustrating than you look at these things and then know they’re unavailable”). He believes a dress should fit women across a range of sizes, be crafted extremely well and subtle in its detailing so that it can be worn over and over. That to him is a successful design. He has also distinguished himself at Bottega by streamlining the accessories into a limited number of shapes that evolve each season—the Cabat, a basket-weave tote that became an instant best-seller when it debuted in 2002; the Knot, a clutch often name-checked on the red carpet—and manage to be both recognizable and discreet. It’s an aesthetic Maier parlayed into his campaigns, for which he alone selects the items featured. The photographers, some of whom, like Stephen Shore, have never worked with models, are then given the dresses and bags to play with, almost like props.

“I think I understood what he was after at the very beginning, which was an image with character,” says Shore, who shot the spring 2006 campaign at an old mansion on Long Island. While he had recently stretched outside his art photography with campaigns for Titleist and Orange, a European mobile-phone company, Shore had yet to break into fashion; since his collaboration with Maier, he has gone on to work with Urban Outfitters and Nike. “I admire people who are interested in taking chances,” Shore notes. “In the late Seventies, I spent a couple of months photographing the Yankees’ spring training. And then I went to a new magazine that was starting up. And [the art director] said, ‘Well, I really like your portraits of the baseball players. Do you think that you would be capable of taking portraits of football players?’” Shore sighs. “That is a very different kind of thinking than Tomas, who is saying, ‘I love his interiors, and I like the way he sees. I would like to see what he would do with fashion.’”

Indeed, with the exception of Annie Leibovitz (fall 2007), Nick Knight (fall 2008) and Steven Meisel (fall 2009), Maier has assumed the role of fashion-world initiator for the photographers he works with. He has a wish list—at the top was Irving Penn, who repeatedly declined up until his death, at 92, last year—and he counts Thomas Struth and Longo’s pal Sherman among those to be crossed off. But if Maier is nervous about approaching the artists, they are more startled by the invitations. “Shocked,” as Shore puts it. “Panic and fear,” says Goldin.

“I was surprised but really grateful,” says Barney, who shot a series of pastel-saturated images at Mar-a-Lago in Palm Beach for spring 2007. “It took me a long time to get a commercial job, I think because [art directors] worry I would try to control everything.” Maier, Barney explains, didn’t seem concerned that she would dominate the shoot. “The clothes are the ruling element,” says Barney, “but Tomas gave it over to me. He has real confidence in the people he works with.”

Of which, on set, there are few. “I think the more people involved, you’re always watered down,” explains Maier, whose own publicity team steers clear of the action. “You want to have very few people around, to keep it very intense.”

Perhaps no shoot better captured Maier’s craving for intensity than the one he did with Goldin for spring 2010—a collection that focused on colors and canvas—at a crumbling Staten Island house. The pair had a rocky start, in part because Goldin wanted to hire model Erin Wasson, a no-go for Maier, who preferred a little-known, albeit stunning, Russian blond named Anya Kazakova. “I thought, Oh, I can’t possibly work with a blond, and then she turned out to be absolutely lovely,” says Goldin, who adds that Maier spent most of the shoot in another room (a scout helps select all the locations). His absence was not because of their initial tension, Goldin explains. Maier simply didn’t want to intrude on her “process.” In fact, Maier and Goldin are similar in certain ways: They both cite Cristóbal Balenciaga as a favorite designer, and each wanted the images, which are imbued with natural light, to be authentic to Goldin’s style, in other words, far from hyperproduced. “I never thought I’d be able to do a campaign,” Goldin admits. “People would talk about hiring me and then they’d hire somebody else. [Those photos] would look like mine but totally devoid of any red blood cells. It’s really brave of him to use me, actually.”

And while Goldin’s campaign shots are much more polished and subdued compared with her raw images of New York’s subcultures, circa 1986, there is, as with the austere black and white portraits by Lord Snowdon (fall 2006) and the cool exuberance of Longo’s photos, a distinct imprint. Just don’t expect to see her name, or that of any of Maier’s collaborators, on the ads any time soon. “When I get the layout [from the art directors], it has the name on the bottom, and I say, ‘You can take that off right away because it’s insulting,’” Maier says. “If you know anything about photography, you recognize it. If you don’t recognize it and you have your doubts, look it up, you know?”