Vali Myers—a ravishing, opium-addicted Australian-born dancer and artist—bewitched the bohemians, beatniks, and aristocrats of ’50s Paris with her sultry, disheveled demeanor. And more recently, her spirit seems to have cast a spell on Miuccia Prada and Marc Jacobs, whose fall runways were full of Myers-esque women on the verge of coming undone, both literally and figuratively. “When I see pictures of Vali in a jazz club, wearing an oversize shirt and pencil skirt, her beehive falling apart, I think of a free spirit,” says the stylist Olivier Rizzo, who referenced Myers in his work for Miu Miu last season. “I see a cool girl who is totally relevant today.”

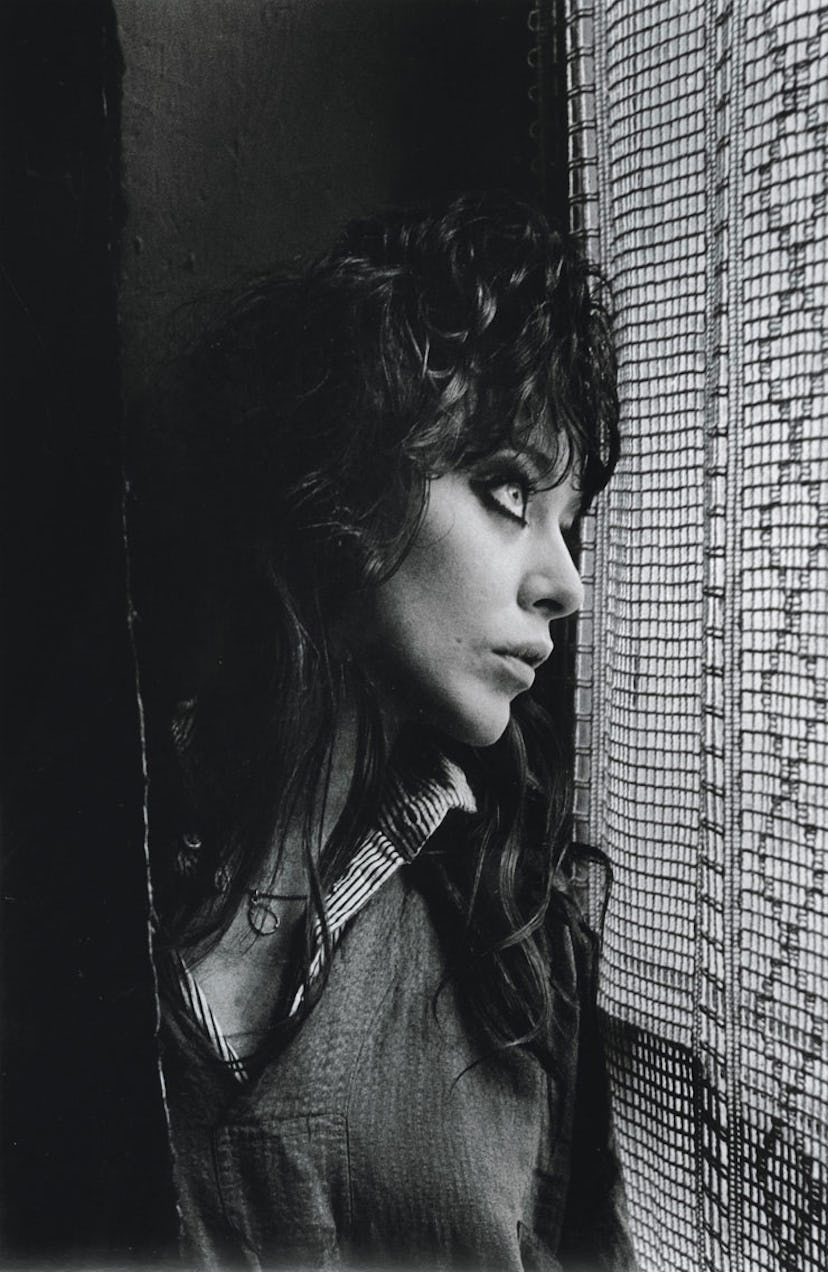

In midcentury Paris, Myers was a symbol of the “restless, confused, vice-enthralled demimonde that populated certain cafés on the Left Bank,” wrote George Plimpton, who published a series of her self-portraits in the Paris Review in 1958. Plimpton’s accompanying essay recounted how bartenders in the little boîtes where she danced nicknamed her le chat, while concierges called her la bête. Others referred to her as la morte vive because of her corpse-white face and kohl-laden eyes; the makeup, she explained, was protection against evil spirits.

Men enjoyed her company, according to the writer Gabriel Pommerand, “in the sense one might enjoy being accompanied by a cheetah on a leash.” Myers planned to kill herself at 23, using arsenic, before an audience of friends and her “feeley,” a fox fur she always kept nearby. (Her Irish-poet heroes, she reasoned, had died young.) She frequented dark, smoky clubs like Tabou or l’Escale, where she danced to the rhythm of African bush songs. “A sinuous shuffling, bent-kneed, her shoulders and hands moving at trembling speed to the drumbeats” is how Plimpton described her moves.

Myers shot by Edward van der Elsken.

Myers arrived in Paris in 1950, at age 20, after studying with the Melbourne Modern Ballet Company. She hung out with Django Reinhardt, Jean Genet (“Congratulations on your maquillage,” he famously told her), Tennessee Williams, Salvador Dalí, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Allen Ginsberg. On a trip to Vienna in 1952, she met an architecture student named Rudi Rappold, whom she married in 1955.

By that point, Myers had become addicted to opium. “I was very fragile and frail, rarely leaving my room till late at night,” she wrote years later to the Dutch photographer Ed van der Elsken, who had included her in his 1956 book Love on the Left Bank. “For three years, I didn’t see the sunlight.” Facing escalating problems with the French immigration authorities, Myers and Rappold hitchhiked to Italy in 1958. They leased a small house in II Porto, a deep valley in Positano, at the base of a towering cliff.

It was the perfect hideaway for the eccentric couple, who eventually were joined there by a young Italian, Gianni Menichetti. He soon became Myers’s lover and, later, her biographer. They kept pigs and goats and took in dozens of stray dogs; her beloved fox, Foxey, was with her for 14 years. The locals mostly kept their distance, fearing that Myers was a witch. Though she rarely left Il Porto, her fame quickly spread—Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithful came to visit and bought Myers’s drawing The Death of Jezebel. And at the invitation of the folksinger Donovan, Myers traveled to London in 1967 to dance to his song “Season of the Witch” at the Royal Albert Hall. Her fee? One Nubian goat.

From left: fall 2013 looks from Prada, Marc Jacobs, Louis Vuitton, and Marc Jacobs. ****

Eventually, Myers found herself in need of actual money, so in 1971 she checked in at New York’s Chelsea Hotel, where she knew she could sell a few paintings. “One of her favorite sayings was that life is ‘like a comet, burning bright and fast,’ ” recalls Chris Stein, a cofounder of and the guitarist for Blondie, who befriended Myers at the Chelsea and subsequently named his daughter after her. “She was a magical thing: highbrow and completely of the streets, too.”

Patti Smith was so awestruck, she asked Myers to tattoo her knee with a lightning bolt. “Vali was a big hero of mine when I was 14,” the punk artist told Interview magazine in 1973. “She was the supreme beatnik chick—thick red hair and big black eyes, black boatneck sweaters, and trenchcoats.” But by the time Smith met her idol, the wild gamine of Paris had transformed almost beyond recognition. She wore outlandish peasant costumes and had tattooed an outline around her mouth and inked her hands and feet. Her hotel room was filled with other denizens of the Chelsea underworld—Gregory Corso, William S. Burroughs, Abbie Hoffman.

After 43 years, Myers returned to Melbourne in 1992 and spent her days creating a new bohemian oasis and enjoying her quasi-celebrity. The wild, rebellious proto rock chick of the Rive Gauche had found her place in the world. She told Menichetti a decade before her death in 2003: “I feel like a bird that has spread its wings—finally. It’s a miracle!”

Photos ©ed van der elsken/Nederlands fotomuseum