During the pandemic, it seemed like everyone picked up a new hobby while quarantined at home—baking sourdough bread, spray-foaming mirrors, playing tennis, and hosting fashion shows on Animal Crossing. But the most viral activity to catch my attention was a newfound obsession with golf—an interest percolating among peers I never expected to be interested in the sport: skaters, rappers, sneakerheads. Seemingly overnight, my Instagram feed transformed into a virtual golf course dimpled with videos of men at driving ranges. Of course, they were also all dressed up to play the part. (This viral video is one of the clips that has felt particularly inescapable.)

What I didn’t realize was that this shift in perception has been a long time coming in the game of golf. The ideal spokesperson for a golf-oriented brand doesn’t necessarily have to be a professional golf player. The aesthetic itself has been coined “golfcore,” but with a new wave of golf apparel hitting the market like Quiet Golf, Macklemore’s Bogey Boys, and Drake’s NOCTA Golf collection with Nike, it’s evident that this moment is so much bigger than a pandemic trend.

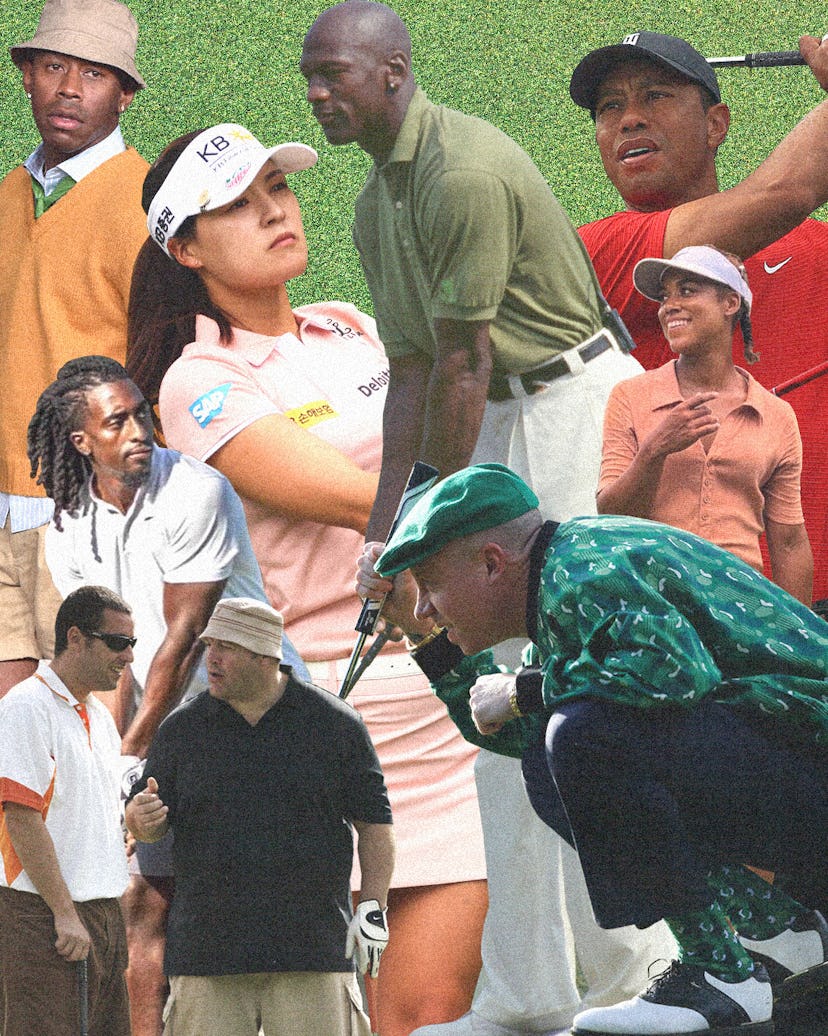

For centuries, the stereotypical golf player has been an old white man wearing a polo, classy shoes, and ill-fitting tailored pants. Troy Mullins, a Long Drive golf champion, refers to players like Ben Hogan and Gary Player as the original archetypes, and points out how Tiger Woods was an anomaly “not only because of his race but his physical strength and powerful game.”

Mullins recalls how, when she first started to develop an interest in golf, she felt discouraged by the lack of investment in women’s golf specifically. “I was even told by a few companies that they don’t pay their female golf ambassadors, as if that was something to be proud of,” she says. However, the growing attention has been promising—women’s World Long Drive was broadcast on television for the first time ever in 2017. With so many different types of styles and people that play, Mullins doesn’t believe that a single archetype of a golf player exists.

Still, the golf community has a lot of work to do to make people feel comfortable within the scene. Founders of golf apparel brands, like Will Gisel and Colin Heaberg of Whim Golf, Erik Anders Lang of Random Golf Club, and athletes like Jarrell English (also known as Rory Blaklroy) and Mullins, all note they have struggled with feeling welcome at one point or another, whether on the basis of their gender, race, or having a more “alternative” appearance compared to the image associated with the golfer stereotype.

But in mainstream popular culture, the narrative of who is allowed to be an ambassador of the sport has actually been shifting for decades. Whim Golf’s founders both share a vivid memory of the Michael Jordan golf collaboration with Wilson in the 1990s. As kids, they didn’t have the patience for the sport, but came around to it as adults. Fast-forward to 2020, when the documentary series The Last Dance debuted, and viewers could see Jordan’s golf obsession on full display. Heaberg cites this as a prime example of a pivotal moment in pop culture when something finally clicked—the generations that grew up with Jordan on television as an NBA champion are now at an age where “they have discretionary income and they don’t play sports anymore,” and when they see someone like him playing the sport, they realize “you don’t have to be this stereotypical golfer.”

When the “golfcore” aesthetic blew up this past summer, Whim Golf was automatically associated with the trend—even though the brand has become popular with seemingly unexpected types of people, including Daniel Fang from the band Turnstile. Gisel doesn’t hesitate to denounce the link to golfcore, arguing that while golf may be a part of their name, Whim is first and foremost a menswear brand driven by “a mission to present golf in a way that might make people reconsider whether or not they like it.

“That notion of golfcore makes us really uncomfortable and almost cringe,” Gisel adds.

Heaberg agrees, insisting that “the most golf-centric thing we do as a brand is build free mini golf courses in cities.” (In an effort to “grow the game,” Whim periodically offers free pop-up golf putting courses in places like New York City and Los Angeles.) He believes that their other interests are what make them stand out as a brand because they don’t solely focus on the sport. “We were athletes before we were designers, and golf presented an opportunity to make clothing that is real and associated with sports at the same time,” Heaberg says.

English, a golf influencer who has become a huge hit on Instagram and TikTok, says authenticity should be the focus for golf brands. He didn’t originally set out to become an ambassador for the sport—he initially got into the game during his last year at Texas Lutheran University, where he played collegiate basketball. Over the past three years, English turned his passion into a source of income through brand partnership deals, but as a Black man, the most challenging aspect has been the expectation of looking the part and mimicking a sense of sophistication. The last thing English ever wanted to do was stand out in a space where he wasn’t always welcome. (For the record, he says he’s had a “significantly higher amount of positive experiences” overall.) These days, English is less concerned about separating his life on and off the course—braids and all. “I love showing that it’s just skin,” he says. “It doesn’t show where my heart is or my skill level.”

What English and his audience of 20,000 followers represent is the demand for new faces on the golf scene. He also pays extra close attention to whether or not apparel companies will try to replicate something “without including the people that created it.” He adds, noting that he’s eager to see more BIPOC migrating to the courses for the purpose of having fun. “I definitely have my interpretation of how the course should meet the culture.”

Even for those who might fit the bill of a “stereotypical golfer,” the golf world has not always been the most welcoming. Before Lang launched Random Golf Club, he found it difficult to fit into the crowd that was presented to him as a white cisgender man, and didn’t opt into the sport until he reached his thirties. “This game had such a massive PR problem that a potential benefactor of the game itself was deterred by a societal definition of golf—which, unfortunately, for the most part, is accurate,” he says.

When Lang joined a private country club in Los Angeles, the vibes felt extremely off: he found himself within this community of carbon copies that nonchalantly tossed around sexist and racist comments. “My problem was that I didn’t have a club that I wanted to be a member of,” he adds. “I didn't have a club that represented itself based on the needs of humanity that is as diverse as every person on the planet.” He wanted to find more players like him, which he describes as “people with tattoos, people who didn’t like collared shirts, people who just played nine holes and didn’t care about the TV version of the game.” (To this day, he still doesn’t identify as a textbook “golfer.”)

After that country club experience left a bad taste in his mouth, Lang made it his life’s work to facilitate spaces where everyone is welcome to play golf in a format that doesn’t fit in an out-of-touch mold. Producing affordable gear and clothing is one small part of the larger mission to build a roaming community and reclaim the game. (Random Golf Club is currently in the process of building a hybrid space in Austin, Texas where the public can congregate for free.)

Haley Wineman, a community manager at Random Golf Club, says she felt too intimidated to pick up a golf club when she was younger, but now she’s one of the many voices pushing the space in a more progressive direction. “I never thought of myself as someone who would golf, I did the more traditionally female sports like dance and cheerleading,” she says. “[When] making the transition to golf, I knew this would be something people might look at me weird for doing.” As Wineman further explains, the goal of hosting nationwide meetups for their 140 chapters is to strip away expectations, and cultivate a supportive place where people can explore the game of golf in a non-judgmental way. “Nobody cares what your score is, nobody cares what you’re wearing or what clubs you’re using,” she adds. “Everybody is just there to hang out and make friends.”

Mullins notes that more feminine apparel brands have also emerged within the women’s golf scene in recent years. “In the beginning, I definitely struggled trying to find the only clothes that fit my style, but also fit my more athletic body type,” she explains. “I had to look outside of golf clothing to find things that worked within the golf world but also appealed to my fashion sense.”

Golf is still viewed as a status symbol for the most elite tier of society, so the financial commitment is usually the main barrier to entry. (The equipment alone is expensive, but throw in the long list of restrictions and the costs add up even more.) Upgrading the dress code for golfers is a small step to repave the road toward leveling the playing field. The next action item on the agenda should involve providing access outside of the country club model through affordable indoor spaces, driving ranges, and simulators.

“You don’t need that much space to build a microcosm of a golf course; in a way that people can start playing a little bit to develop an interest in it and then graduate to the next thing,” Gisel says. “We’re trying to package golf in a way that you can touch.”

As Heaberg puts it, “golf has been held hostage because there are people that don’t want new players to play.” While there will always be those who fight change for the sake of preserving stale traditions, the next generation isn’t seeking their approval for the next big cultural reset.

This article was originally published on