Michael Hauptman Contemplates Humanity’s Place on Earth in Of Matter and Time

The noted fashion photographer will release his first book in June of this year—a meditation on human beings’s relationship to nature and technology.

Welcome to Ways of Seeing, an interview series that highlights outstanding talent in photography and film—the people behind the camera whose work you should be watching. In this week’s edition, senior content editor Michael Beckert chats with photographer Michael Hauptman, whose new book Of Matter and Time will be released in June.

Congratulations on your first book. Tell me what it’s about, and how long you’ve been working on it.

This book, which I’ve been working on for about 10 years now, is a distillation of all the things I’ve been thinking about and feeling my whole life. It’s a meditation on humans’s relationship to nature and technology and our small, small place in this known universe.

I remember when I was about 11 years old, I would always think about how small earth is, floating around in our galaxy. I found immense comfort in visualizing how profoundly small we are. I wanted to give this book the feeling of “Earthy” and of a singular humanity—like a snapshot of where we are now—with a bit of creative interpretation and a UFO here and there. I was thinking about whether technology will bring us closer to nature and one another, or isolate us even more. Nature has always been so important to me and being born in the mid ’80s, I feel like we really got the full ride of hardly having tech in our lives to becoming part-cyborgs today.

Is it strange to look through this book and see work you created in 2006 next to work you’ve made more recently? Do you see things you’d change about the older work now?

Surprisingly not. I feel pretty lucky to be able to look at that work and still be excited. I look at it now and so clearly see how it informed and inspired my work that came after, so it feels only right that it’s included in my first book.

Is there a single picture from this new book that really stands out to you or feels most emblematic of the book’s meaning?

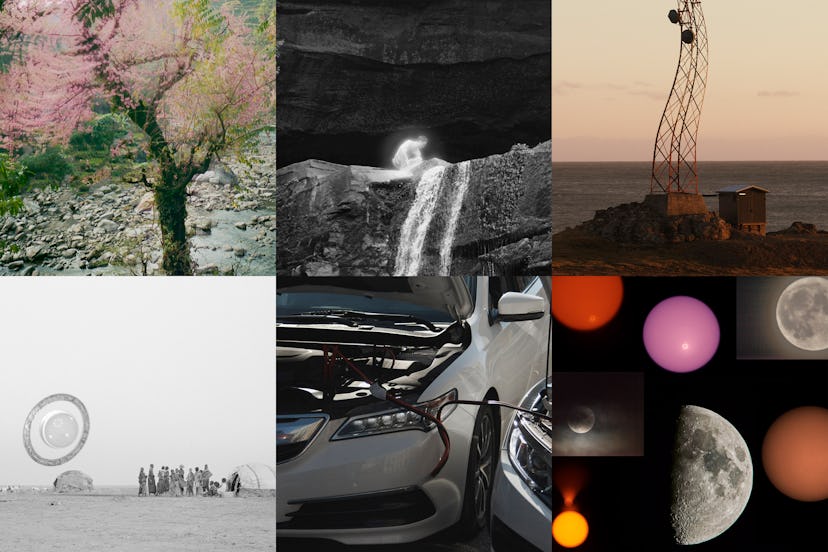

These two come to mind. The image on the left (below), because it’s one of the first times I made a fake “ufo” in a picture. It felt like an innocent interaction and relationship to a synthetic being—my imagination of what a human’s future could look like. The image of the tree (below) because, for me, it represents beautiful nature and human synthetic ripple emanating, while simultaneously representing the power and unseen pulse of mother nature.

Photographs by Michael Hauptman, from his new book, Of Matter and Time (2022).

Take us back a bit. When did you first get into photography?

When I was around 12 or 13, I was fortunate enough to take a photo class at school. In a full little black and white darkroom, we got to learn all the traditional foundation basics of developing and printing by hand. It felt like magic—as someone who never really enjoyed being in school, I couldn’t believe we got to do this.

It wasn’t until I was 13 or 14 that I even realized being a photographer was a job. I originally wanted to be a photojournalist after seeing a book of Dan Eldon’s work—seeing that forever changed how I felt and what I thought was possible to do with your life. Around 19 or 20, I learned what a fashion photographer was and did and got into it.

Was there someone in your life who encouraged you at a young age to pursue the arts?

I was fortunate enough to have support from both my parents and grandparents, who actually bought me my first camera when I was around 13 years old. My mom studied art in college so I think she was pretty excited to see me take to the arts.

Photograph by Michael Hauptman, from his new book, Of Matter and Time (2022).

What did your first pictures depict?

Nature landscapes, self portraits, friends. We used to go out at night and take photos in the alleys of our small town. We thought we were very edgy.

What’s it like to release a personal body of work after becoming known as a prominent fashion photographer, lensing covers for The FACE and shooting campaigns for brands like Gucci?

Since I’ve been thinking about this and working on it for so long, it feels completely natural for it to come out. For so long now, I’ve wanted more personal work of mine to be out in the world to help inform, represent, and expand the scope of what I make and who I am. I always strive to have commissioned work live as closely to personal work as possible.

Do you get nervous before big editorial or advertising jobs? Do you have a pre-set ritual?

I used to, but it was never that bad. Because I grew up playing competitive basketball, I learned from a young age how to handle nerves, feel calm, and just focus.

Many of our Ways of Seeing readers are just finishing up university. What advice would you give a younger creative looking to make a living in photography?

Self-referral and looking inward. All we truly have is our individual thoughts and feelings, and letting that fully come out in your work is the biggest success. It’s so easy these days to emulate and copy, but for me, the real joy and success comes from when you’re able to transpose yourself into your work.

The color palette in your work really stands out. It’s slightly desaturated and calm. What inspired this style?

It wasn’t so much a conscious choice. It was more of a reaction to feeling like everything was too vivid and saturated. I wanted to represent a more realistic and less “digital” feeling in my work. But yes, I think you might be onto something—maybe subconsciously, I was going for a more mellow, calm image.

I like to think of an artist’s career as a lifelong journey. What are you most proud of so far on your journey?

This book is definitely something I am most proud of. I would also say the Marni campaign in 2017: it was my first major campaign and I was able to come up with the creative concept, which actually touches on similar thoughts and ideas as my book—exploring humans’s disconnect from nature, even when we’re surrounded by it.