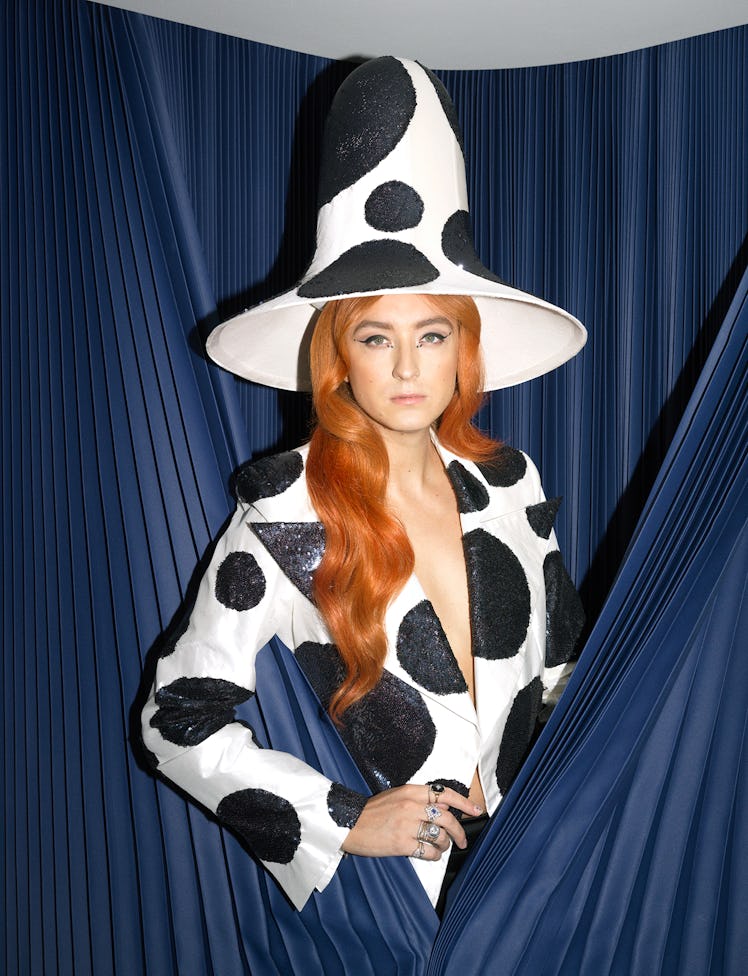

For W’s annual The Originals portfolio, we asked creatives—pioneers in the fields of art, design, fashion, comedy, activism, and more—to share their insights on staying true to themselves. See this year’s full class of creatives here.

You’re 26 years old and have only five collections and three fashion shows under your belt, but you’ve already managed to get Beyoncé to wear one of your peacock-feather headpieces and Harry Styles to slip into a suit-slash-dress you designed. What’s your secret?

The women on my team who make my dreams come true are witches, I swear. I call them witches in a good way, because it’s like there’s this cauldron and I’m throwing feathers and sequins and lace and tulle into it, and they’re stirring it all together and making sure it comes out right. I work with strong women who are always finding new ways of getting this little boy’s dreams of huge, head-turning, gender-fluid creations where they need to go. By the time I’m sketching, they are already measuring the doorways and figuring out what the biggest crates are to ship these crazy innovations from our tiny studio in London to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

How do you approach the business behind your witches’ brew of fashion?

It’s quite incredible that it’s demi-couture and it’s gender-fluid and that the clothes are as over-the-top as they are—and that we’re actually turning a profit. Everyone loves McQueen for his references and how amazing he was as a designer, but I also reference how he was as a businessperson. For the first few McQueen collections, I believe, none of the pieces went to a retailer. Those early collections were really just to get the brand ethos out there. And that’s what I’ve been really trying to do with my creations: show what I can do and who I am.

That’s an original way to think about a designer’s legacy.

I think people underestimate me as a businessperson—because of the American accent, the long hair, the fact that I like to dress up and be glamorous. Even at Central Saint Martins, people would call me Jessica Simpson because I would wear boot-cut flares and blouses. I would always be like, “I hope I become as big as Jessica Simpson—she’s a billion-dollar conglomerate.” Whether it was Viktor & Rolf or Thierry Mugler, the first thing I was obsessed with about those brands was their business model. How could they do incredible couture and still make revenue? At school, I remember thinking that if I wanted to do amazing pieces like Mugler, McQueen, or early Galliano, then I needed to find a business model that would work for me.

It was recently announced that you’ll be the new creative director of Nina Ricci. In what ways do you see the label being in line with your own distinctive approach to fashion?

Honestly, to get the opportunity to explore the nuances of femininity in such an iconic house is a true dream.

You live in London. How do you think your American accent shapes how the Brits perceive you?

The thing I love about America—and I think this is both bad and good—is that the country stands for being a place where anything is possible. You can take over the world. Not to generalize, but British people tend to be very humble and quiet, almost self-deprecating. They’ll be like, “Oh, it’s not that good,” whereas I have this American thing where I walk into meetings being like, “This is the best thing you’ve ever seen.” My friends roll their eyes when I talk about wanting my work to be a huge success. They’re like, “How can you talk like this?” And I’m like, “Well, I have to, because I need to find 200 grand to make this show happen!”

What was your upbringing like?

My mom is Mexican-American, and my father is British. I was born in California, but we moved 28 times before I left for university, so I lived in California, Arizona, Oregon, Seattle, and Washington. And then France for a year. Moving so much forced me to perfect the elevator pitch of who I am. Ever since I was young, I had mannerisms that society deems as queer. I came out when I was 9. I was living in Arizona at the time, which was not the place to be as an out queer kid. My mom moved me and my sister back to California because the bullying got so bad. Still, Arizona was where I learned that I liked fucking with people’s expectations a little bit. It was like, Oh, I’m going to wear a pink polo shirt because everyone is going to freak out on the playground and say things.

That same modus operandi is now being used to test the gender binary in fashion.

When you see photos on social media of me talking to people at dinners or read articles about how open-armed fashion has been to me, everything looks so amazing from the outside. But what you don’t see is that for the whole beginning stages of my career, everyone treated the idea of gender fluidity as being like a costume, not fashion. The campiness and references to different time periods were immediately seen as theater and not something to really be taken seriously. Don’t get me wrong: I love theater. But I’m not here to be a costume designer. I’m here to be a fashion designer—just one who happens to have a message.

Hair by Terri Capon for Color Wow at Stella Creative Artists; makeup by Joey Choy for Charlotte Tilbury Beauty at Premiere Hair and Makeup; fashion assistant: Andrew Burling; special thanks to The Standard Hotel, London.