Theophilio and Black Fashion Fair’s Latest Collaboration Is a Form of Protest

Last summer, in the wake of the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and worldwide Black Lives Matter protests, fashion brands and businesses hustled to address how they’d perpetuated anti-Black racism and what they would do to reconcile it. Companies’ social media posts and mission statements on their websites were a sight to see: after decades of appropriating Black fashion and culture, the fashion industry seemingly realized—and acknowledged—major trends have origins in the Black community. Antoine Gregory, who runs the platform Black Fashion Fair, and Theophilio designer Edvin Thompson are well aware of this fact. With the release of their latest joint capsule, Family Portrait II, they aim to unlink anti-Black trauma from the fashion narrative, and invite in a different method of storytelling through design and community.

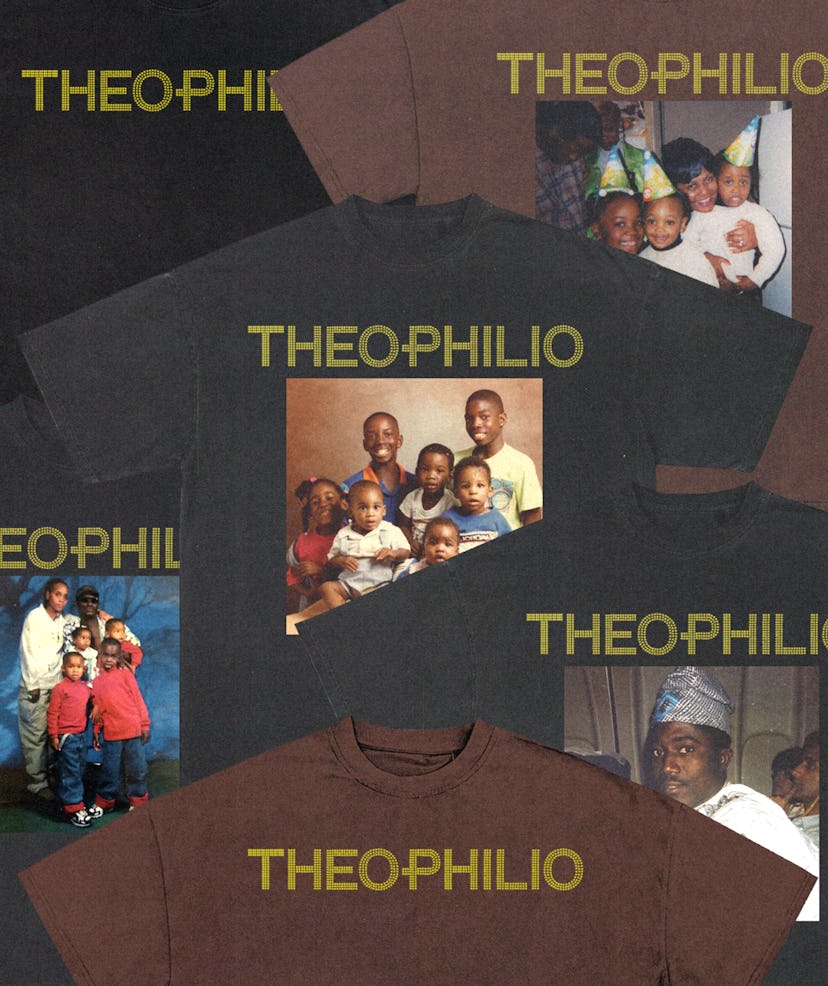

Family Portrait II, which drops this month, will feature a limited run of black and brown shirts priced at $178 each; shoppers will have the opportunity to submit their own family photos to be featured on a custom Theophilio tee. And to celebrate the launch, BFF and Theophilio will host a “Family Reunion” celebration on Juneteenth, a holiday that observes the emancipation of slaves in the United States.

Thompson and Gregory previously collaborated on an initial Family Portrait capsule in February 2021. The collection, which featured six oversized shirts bearing Swarovski crystal embroidery spelling out “THEOPHILIO” and an enlarged photo of the designer’s family, centered Black family life while highlighting Thompson’s roots in Jamaica. “What he did with his initial Family Portrait tee was really cool because it showed exactly where he came from,” Gregory said. “It was important for me to take the story that he was creating and make it accessible to everyone.”

Family and Jamaican tradition are recurring themes in Theophilio collections. The brand, which was the recipient of this year’s CFDA Fashion Fund Grant, often features nods to Thompson’s upbringing—incorporating his own family’s portrait on a tee, therefore, seemed like a natural move. The photo Thompson used is a fairly stock studio-shot photograph, but its significance brings the intention of the collaboration full-circle. “I remember that photo being taken a couple months before I got my green card to fly to America,” Thompson recounted to me. “My dad decided to take us to get our last family photos before we all separated for seven years.”

While Theophilio is not a brand known for tees, this offering salutes the graphic tee as a style staple in the Black community. Graphic t-shirts date back to the Black Panther movement of the 1960s—the style saw a boom in the 1980s with hip-hop fashion pioneers The Shirt Kings. Pegged as “The first Black clothing line straight from the streets,” custom tee innovations became cornerstones in defining street fashion of the time. These customizations made it easier for the Black community to access trends that would soon be coveted by mainstream shoppers. The idea of accessibility (which is sometimes treated as “radical” in the high fashion world) is paramount for Black creators who want to foster a sense of community in fashion, and Thompson is no different. “If a customer doesn’t see themselves in pieces from my collection like corset tops or the grommet pants, but they can see themselves in a graphic tee and they want to support, that’s important,” Thompson added.

Gregory said the thesis behind the second half of this project, is to “reconsider and revalue our own family photo collections, to combat a legion of existing imagery that reinforces stereotypes inflicted upon and used against Black people.” This idea also translates to the unearthing of Black family life through photography, “as major institutions don’t collect our images, and those that have catalogued any trace of Black life, the representation is bleak,” Gregory said. “Here is an opportunity for us and the world to see another side of Blackness that isn’t rooted in trauma or pain, but happiness, love, and celebration of the family.”

The reclamation of the Black image is an ongoing practice in the photography world, and BFF and Theophilio hope to extend that practice to the fashion space.

“Black people have used imagery, have used fashion—specifically the t-shirt and the idea to customize it—to construct political aesthetic and cultural representations of themselves in the world that they live in because no one else was doing it,” Gregory said. “If you think about the ‘Free Huey’ shirts by the Black Panthers, those are the only things we had access to. We weren’t given access to be in ateliers. We used customized t-shirts when someone passed away to honor their memory. We’ve always existed in this space.”

“If our artwork, our message, our posters weren’t allowed in the building, it would be on our bodies, which would be moving around carrying that message,” Thompson added. “It’s a form of protest, in a way.”

This article was originally published on